More poor in urban areas by 2030

Chasing pot of gold people have long been setting off for urban areas from rural Bangladesh.

But that pot would be incredibly hard to find come 2030 as per the World Bank’s latest report: more than half of Bangladesh’s poor households will live in urban areas by then even though 8 in 10 poor currently live in rural areas.

“Urban is the frontier in poverty reduction,” said the report styled ‘Bangladesh Poverty Assessment: Facing Old and New Frontiers in Poverty Reduction’.

The report, which is based on the latest iteration of the Household Income and Expenditure Survey, was unveiled yesterday in a daylong event at the Amari Dhaka, where Finance Minister AHM Mustafa Kamal was the chief guest.

Very little poverty reduction occurred in urban areas between 2010 and 2016 and the share of urban people living in extreme poverty remained the same, found the report.

In 2010, 21.3 percent of the urban population were living in poverty and 7.7 percent in extreme poverty. Six years later, the ratios were 19.3 percent and 8 percent respectively.

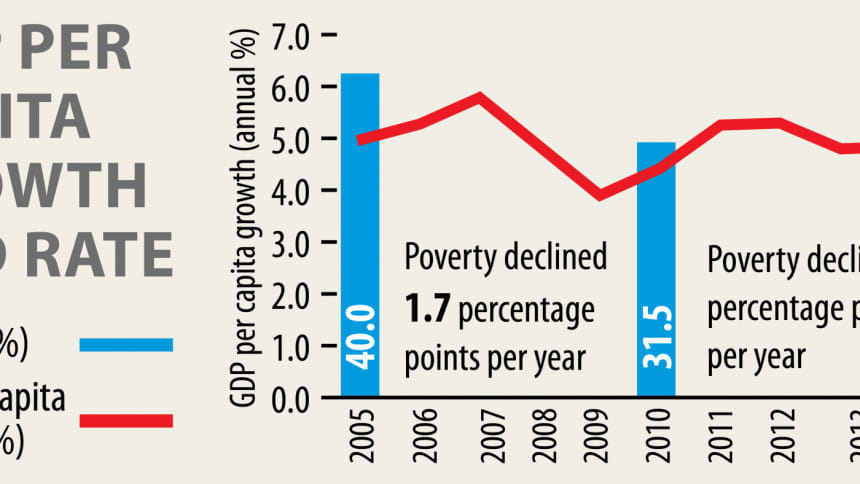

As a result, the rate of poverty reduction declined, the report said.

The finding is rather perplexing given the tremendous pace of economic growth during the period.

About one in four Bangladeshis still live in poverty, while almost half of those living in poverty live in extreme poverty and are unable to afford a basic food consumption basket.

Using the international poverty line, a measure that allows comparison with poverty levels in other countries, the rate of poverty in Bangladesh is relatively high by regional standards, the report said.

In Bangladesh 14.8 percent of the population live in poverty, bested only by India in the Saarc region. Some 21.2 percent of the population still live under the international poverty line in the neighbouring country.

Only 0.8 percent of the population live below the international poverty line in Sri Lanka and 3.9 percent in Pakistan, according to the study.

“Bangladesh has an inspiring story of reducing poverty and advancing development,” said Mercy Tembon, the WB’s country director for Bangladesh and Bhutan.

Since 2000, the country has reduced poverty by half. In the last decade and a half, it lifted more than 25 million out of poverty.

“However, there is no room for complacency,” she added.

Furthermore, more than half of the population in Bangladesh can be considered vulnerable to poverty, as their levels of consumption are close to the poverty threshold -- a proclamation that the finance minister strongly disputes.

“There is no chance for those who have come out of poverty to fall back into it -- we have taken plenty of measures,” Kamal said.

The reasons for the decline in urban poverty reductions include slow manufacturing job creation, reduced female labour force participation (FLFP) and increase in poverty among the self-employed in the service sector.

There has been little growth in the share of the Bangladeshi labour force engaged in industry, and this has limited the amount of poverty reduction derived from the country’s industrial growth, the report said.

The slowdown in job creation in the garments and textiles sector is partly responsible for the diminishing rates of FLFP.

Between 2005 and 2010, overall labour force participation in urban areas increased because of a substantial increase in FLFP. The expansion of the garment sector was an important force in raising FLFP as 80 percent of the employees are female.

But between 2010 and 2016 FLFP declined about 4 percentage points.

The stagnation in poverty reduction in services is also concerning given that around 44 percent of the urban poor are part of households primarily engaged in the sector, the report said.

“Tackling urban poverty is critical,” Mercy said.

The urban poor may be better off than their rural counterparts in terms of income but worse off in key social indicators, said Hossain Zillur Rahman, executive director of the Power and Participation Research Centre.

Many poor urban households live in slums, facing poor housing, insecurity and overcrowding.

He recommended rolling out health safety net programmes for urban poor.

“People are at the risk of falling into poverty for lack of healthcare. Therefore, urban health safety net has become important,” he said, adding that social protection for the urban poor is a relatively under-focused area in policy discussions.

On the flip side, rural Bangladesh spearheaded poverty reduction from 2010 to 2016, accounting for about 90 percent of the drop in poverty. And industry and services, not agriculture, mostly led the poverty cuts.

“This reflects the slower growth in agriculture during this period but also the fact that agriculture growth was less poverty reducing compared to the past and other sectors.”

Meanwhile, the Western divisions did not see the same gains as the East between 2010 and 2016.

Since 2010, poverty has risen in Rangpur division, the historically poorer Northwest of the country; it has stagnated in Rajshahi and Khulna in the West.

The East and central Bangladesh have fared much better: poverty has fallen moderately in Chittagong and declined rapidly in Barisal, Dhaka and Sylhet.

As the country is facing new and re-emerging frontiers of poverty reduction, specifically tackling urban poverty and poverty in the West, approaches that uncover effective traditional and new solutions must be embraced, the Washington-based multilateral lender said.

“Policies to reduce poverty when poverty incidence is high are different from those when poverty is lower.”

In the past, relatively straightforward measures like the introduction of high-yielding rice varieties could kick-start a process of welfare improvement.

But now, more sophisticated policies are needed to reduce poverty over a sustained period and in a more complex economy.

Continuing Bangladesh’s practices of innovative policy experimentation and learning from other countries’ experiences of similar economic and development transformation will be important to tackle some of the challenges presented.

“We will take measures in the budget to address these issues,” Kamal said, adding that 1 crore new jobs would be created by 2030 and needs- and technology-based education would get priority.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments