News Analysis: Democracy vs graft

The Corruption Perceptions Index released by the Transparency International on Tuesday provides food for thought on corruption and democracy.

Its cross analysis with global democracy data reveals a link between corruption and the health of democracy in 180 countries.

Full democracies scored an average of 75 out of 100 on the CPI while flawed democracies got an average of 49.

Hybrid regimes, which show elements of autocratic tendencies, scored 35. Autocratic regimes performed the worst, with an average score of just 30 on the CPI, according to the analysis.

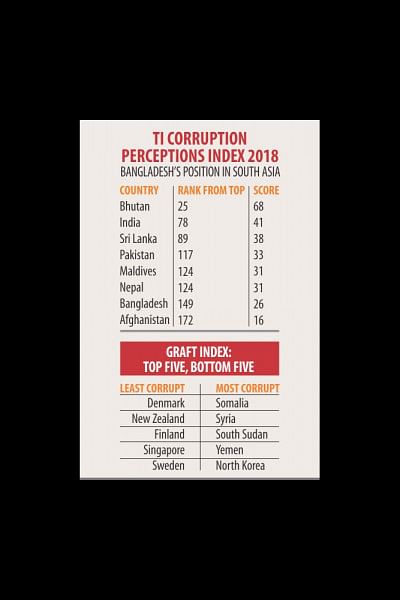

Bangladesh ranked 149th, scoring only 26 against the lowest global average of 43 in the index. Needless to say; it is an embarrassing performance. The score tells where we stand in the categories in terms of functioning of the government.

The reasons behind the poor performance of many countries are more or less the same. The persistent failure of most countries to significantly control corruption is contributing to a crisis of democracy around the world, says the TI analysis.

TI's remarks on the impact of corruption are relevant to all, and we are no exception.

Just a day before the TI released the index, our High Court released the full text of the verdict that doubled BNP Chairperson Khaleda Zia's five-year jail term in a corruption case. The court made a critical observation on the impact of corruption.

“It is beyond controversy that where corruption begins, all rights end. Corruption devalues human rights, chokes development and undermines justice, liberty, equality, fraternity which are the core values of our constitution,” stated the HC.

In the verdict, the court focused on the state of corruption in our country.

“Today, corruption which includes financial crime also in our country not only poses a grave danger to the concept of good governance, it also threatens the very foundation of democracy, social justice and the rule of law,” it observed.

The way the last parliamentary election was held has exposed vulnerability of our democracy. The election was marred by alleged corrupt practices. It is beyond debate that a flawed election is always a threat to democracy.

The TI is not alone in speaking about the crisis of democracy. Its cross analysis incorporates data from the Democracy Index by The Economist Intelligence Unit, the Freedom in the World Index by Freedom House and the Annual Democracy Report by Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem).

Let's take a brief look at the Democracy Index produced by The Economist Intelligence Unit in January this year to know our position.

Bangladesh has been ranked 88th among 167 countries with an overall score of 5.57 out of 10 on the democracy index. It was ranked 92nd with a score of 5.43 in the previous year.

This shows Bangladesh advanced four notches on the latest index. But a comparison with the 2006 score is not encouraging.

In 2006, Bangladesh's overall score was 6.11 on the index. Since 2008, the score has been in decline and has remained below 6.

Based on the scores on the democracy index, the countries were put in four categories in terms of functioning of governments -- full democracy, flawed democracy, hybrid regime and authoritarian regime.

New Zealand, Australia, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, the UK, and 12 other countries that scored above 8 on the index were placed in the category of full democracy.

Due to its poor score, Bangladesh was put in the category of hybrid regime along with 38 other countries, including Bhutan, Nepal and Pakistan in South Asia.

India and Sri Lanka were placed in the category of flawed democracy with an overall score of 7.23 and 6.19 respectively.

Countries that were put in the category of hybrid regime scored greater than 4 and less than or equal to 6.

If one goes through the definition of hybrid regime given in the Democracy Index of The Economist Intelligence Unit, he will find its relevance to Bangladesh.

About hybrid regimes, it says, "Elections have substantial irregularities that often prevent them from being both free and fair. Government pressure on opposition parties and candidates may be common. Serious weaknesses are more prevalent than in flawed democracies -- in political culture, functioning of government and political participation.

“Corruption tends to be widespread and the rule of law is weak. Civil society is weak. Typically, there is harassment of and pressure on journalists, and the judiciary is not independent."

It defined a hybrid regime as a system where "corruption tends to be widespread and the rule of law is weak." Bangladesh's poor score on the TI index indicates prevalence of corruption here.

Our overall score on the rule of law index by the World Justice Project (WJP) last year is also appalling.

Bangladesh has been ranked 102nd among 113 countries with an overall score of 0.41 out of 1. Denmark topped the list with an overall score of 0.89.

According to the Washington-based WJP, effective rule of law reduces corruption, combats poverty and disease, and protects people from injustices large and small.

The state of the rule of law speaks about the state of democracy in a country. The rule of law has been proved an effective tool worldwide to fight graft.

Take Denmark for example. It topped the list of the rule of law index last year and also topped the TI's latest index.

Free media is also considered as one of the effective tools to combat corruption. A free press, according to former chief justice of India RM Lodha, is the heart and soul of constitutional democracy.

The Press freedom Index produced by Reporters Without Borders testifies it. The countries that scored well on the indexes of democracy, corruption and the rule of law performed better in last year's press freedom index too.

Bangladesh could not perform well also on the press freedom index. Its position remained unchanged at 146 as in the previous year with 48.62 points.

Given the above examples, the findings in the TI's cross analysis is worth thinking about.

But the reality here tells a different story. Whenever any global index goes against us, we outright reject it. This is the easiest way. The Anti-Corruption Commission chief and a minister have already questioned the accuracy of the TI index. It seems we are stuck in the same old pattern.

As Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has announced zero tolerance to graft, it now depends on her government's top policymakers whether they will take the TI findings into consideration to improve the situation or follow the same old pattern to counter the TI.

Everyone knows that putting the blame on the messenger never works.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments