Poor feeling the pinch

On Wednesday afternoon, a middle-aged woman went to the capital's Farmgate vegetable bazaar. Looking uncertain, she asked the vendor for a quarter kilo of carrots.

On the scales, there were just three carrots. But suddenly, the woman lifted one carrot from the weighing machine, put it back in the vendor's basket and placed two pointed gourds on the scales instead (prices of carrots and pointed gourds are same). She asked the seller to pack those, paid him and left.

Thinking it might embarrass her, this correspondent did not ask her why she bought so small quantity of vegetables. The reason, however, was obvious and it became clear soon afterwards.

Before the woman could vanish into the crowd, a youth came to the same shop, held up a sheaf of red spinach and asked the price. "It's Tk 30."

The boy, a student, put the spinach down and was about to leave. He looked disturbed. This correspondent asked him, "Wouldn't you take it?"

"Too expensive," he said and was gone.

The story of this woman and this student is also the story of millions of poor and middle-income people in the capital and elsewhere: Prices of most cooking items have shot up over the past two weeks and it's been cutting deep into their pockets.

After remaining stable in recent months, prices of vegetables, eggs and some varieties of fish are recently giving people a hard time.

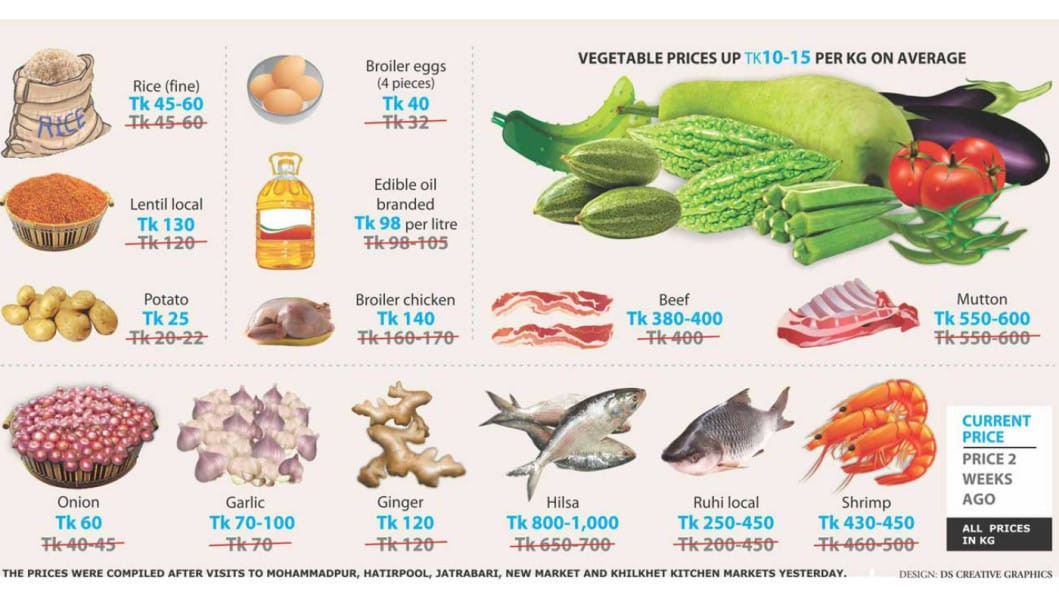

Yesterday, most vegetables sold for Tk 50-60 per kilo in city markets, up by Tk 10 to 15 a kg compared to the prices last week and the week before.

Vendors blame it all on the supply disruption because of the monsoon rain and floods in some parts of the country.

This is partly true, experts say, adding that some traders are taking advantage of the situation as well.

Normally, vegetable production falls during this time of the year, creating a demand-supply gap and thus resulting in a price increase.

But this year, torrential rains triggered by Cyclone Komen flooded croplands in 30 districts in the country's southeast and southwest region, according to the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE).

Around 20 percent of the 87,815 hectares of vegetable fields in these districts have been damaged or affected by waterlogging and flash floods. The districts include Jessore, Jhenidah, Comilla, Narsingdi, Meherpur and Kushtia, it said.

However, visiting the capital's Mohammadpur, Hatirpool, Jatrabari, New Market and Khilkhet kitchen markets, The Daily Star reporters saw there are plenty of vegetables contrary to traders' claim of supply shortages due to the monsoon rain.

Prices of eggs, lentils and onions have also gone up though there is no direct link between their supply and the flood.

Recently, demands for eggs have increased as people turned to it as the only source of protein because of sharp rise in the prices of beef and mutton.

In February this year, beef price went up by about 40 percent after India tightened security at its borders almost stalling smuggling of cattle into Bangladesh. And low and lower middle income people have taken mutton off their menu a long ago because of its high price.

Khondoker Md Mohsin, general secretary of Bangladesh Poultry Farms Protection National Council, claimed that soon after Eid, there was a sudden increase in demand for eggs while supply was low.

This contributed to the price increase, but it would come down in the coming days, he added.

However, prices of both fine and coarse rice, broiler chicken, edible oil, milk and sugar remain the same as in the last few weeks.

Anisur Rahman, who was haggling over a pair of hilsa with fish trader Hanif in Khilkhet, said families like his were struggling to balance their budget because of the price hike.

Asked about the high price, Hanif said, "Supply is low."

In the last few years the government has been largely successful in reigning in the prices of essentials, even during the months of Ramadan. As a result, food inflation came down to 6.07 percent in July this year from 8.14 percent in July 2013.

Ahsan H Mansur, executive director of Policy Research Institute, a think-tank, said the country's macroeconomic stability, exchange rate stability, stable global commodity markets and a rise in domestic production helped the government to maintain price stability.

Vegetables prices normally go up during monsoon when production falls, he said, adding that the agriculture ministry might think of taking up a programme to find out if some winter vegetables can be grown in monsoon as well.

"If we can do that, supply will grow and prices will come down," he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments