No safety in custody

It is human nature to learn from past experiences. But when it comes to deaths in so-called crossfire, law enforcement agencies seem to have learned nothing of the sort.

Rights activists say almost every time a detainee is taken out for a “raid”, he gets killed. So by now, law enforcers should know that they may “come under attack” by criminals, as they claim. Then why don't they protect the detainee?

“Such incidents [deaths in the so-called attack by criminals] may happen once, twice or thrice. It is a big question why law enforcement agencies do not take appropriate security measures, such as providing them with bulletproof vests,” said Sheepa Hafiza, executive director of Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK).

Law enforcers and rights bodies have no record or memory of shootouts in the country before 2004, when Rapid Action Battalion was formed. On August 6 that year, top listed criminal “Pichchi” Hannan was killed in crossfire during a drive while in custody of the elite force.

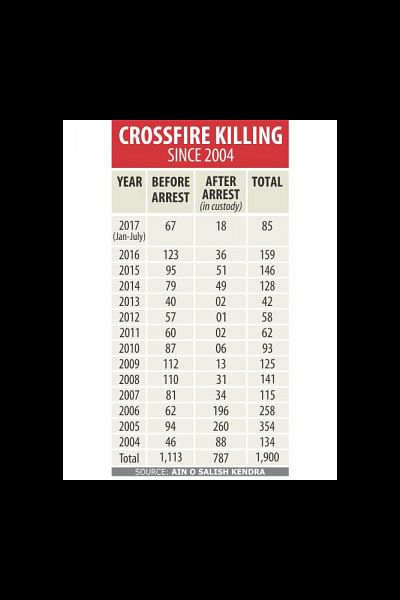

In the last 13 years since, more than 1,900 people have been killed in such incidents involving police, Rab and joint forces. At least 350 met such a fate in 2005, the highest in a single year, according to rights body Ain o Salish Kendra.

The scariest fact is that nearly 800 have died while in the custody of law enforcement agencies, which are bound by the law to protect the detainees.

Section 328 (a) of the Police Regulation reads: “The officer-in- charge of a police station or post shall be responsible for the safe custody of all prisoners brought to the station or post.”

Concerned over frequent custodial deaths, national and international rights groups have long been demanding an immediate end to such killings and thorough investigations into those in vain.

Over the years, victims' families accused police and Rab members of killing their loved ones in the name of crossfire, something the law enforcers deny.

On occasions, families also claimed their relatives were victims of “contract killing” by law enforcers, like the killing of seven people in Narayanganj by Rab members for money from a local godfather, Nur Hossain. (The High Court recently confirmed the death sentence of 14 Rab men, including three high ranking officials, in the case. Another 11 members of the force have been sentenced to various terms in prison.)

With a very few exceptions, these “shootouts” happen at ungodly hours and the media, unable to find witnesses or any other versions, runs the story putting the word “crossfire” within quotes.

The two identical narratives police and Rab offer after such “crossfire” have become clichés by now.

One version is that the victim “was killed in a gunfight” between them and the bad boys.

The other narrative is particularly for those killed in custody. In this case, as the police or Rab version goes, they took the detainee for a drive to recover arms or drugs or to arrest other criminals. Suddenly, his cohorts came out of the blue and started firing at the law enforcers, who fired back in self-defence. And the victim, caught in the line of fire, was hit and killed.

Mysteriously, the one that always dies is the man in the law enforcers' custody, and not his “associates” who “shoot” at the lawmen. And the lawmen manage to escape the stray bullets.

Also, police or Rab members involved in such drives fail to arrest the “criminals” in most cases.

Over the years, rights activists have raised questions as to why law enforcers fail to provide security to the people in their custody.

When alleged criminals are produced before courts or even paraded before the media to announce their arrests, they are well protected with their heads and bodies covered by helmets and bulletproof vests.

Why then the detainees cannot have the same safety gear when they need them the most -- that is when law enforcers take them out for raids?

“Available data show that nearly half of the total victims got killed in custody,” said Sheepa Hafiza of the ASK.

Such extrajudicial killings in the name of crossfire are not acceptable at all, she said. “We do not want to see a single death for lack of security.... Killing in crossfire is a gross violation of human rights.”

Contacted, National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) Chairman Kazi Reazul Hoque said, “Police should be more careful and stand guard when they take anyone for what they say is recovering arms or as part of their investigation.”

Law enforcers claim that they do take “precautionary measures” ahead of such drives, but cannot provide appropriate answers as to why people continue to get killed, particularly those in their custody.

Take the example of Rakib Hasan Russell, a convicted JMB leader.

Also known as Hafez Mahmud, he was caught from Mirzapur in Tangail, hours after he escaped from a prison van on February 23, 2014. The van was ambushed in Mymensingh's Trishal area by suspected militants. One policeman was killed and several others were injured in the attack.

After his arrest, journalists asked the then Deputy Inspector General of Dhaka Range Police SM Mahfuzul Haq Nuruzzaman about the possibility of Rakib getting killed in a so-called shootout, just like hundreds other detainees.

“We will do everything for his security,” the DIG said.

Within hours, however, Rakib was killed in a “shootout”.

Asked why detainees are not protected with safety gear during drives, Saheli Ferdous, assistant inspector general (media) at the Police Headquarters, said bulletproof vests or helmets could not guarantee foolproof security as parts of their bodies still remained exposed.

“When indiscriminate firing takes place, both the police and the accused may be injured," she said.

But why do the drives take place at the dead of the night and, most of the time, away from localities?

About this, she said, "Police usually conduct such operations in quiet time to keep information of the operation secret. What happens then is beyond our control.

“The incidents [death] take place during exchange of fires and the criminals possibly miss the targets for lack of practice…. In many cases, police members suffer injuries. Now, they [cops] don't get wounded by their own bullets, do they? Certainly, they are hit during the exchange of fire [between police and criminals].”

About their failure to arrest the so-called cohorts, Saheli said, “The situation is highly tense when such gun battles take place; everyone is worried about their own safety.”

However, police still try to arrest the associates of the detainees during the drive and also during investigation afterwards.

Mufti Mahmud Khan, director of Rab's Legal and Media Wing, told this paper that they tried to ensure security of the detainees.

In some cases, they needed to take infamous criminals, who had information of firearms and ammunition and about their associates, in operations, he said. “In a few cases, they got killed during exchange of fire with them [other criminals].”

Contacted, Inspector General of Police AKM Shahidul Hoque said he would not talk about crossfire because it was an “old issue”, and then hung up.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments