Pakistanis tried to keep foreign journos away

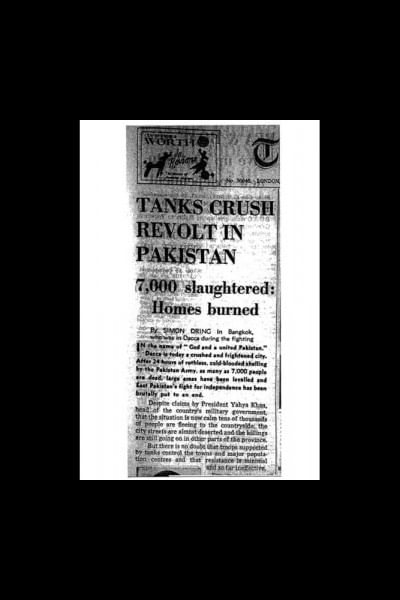

'"In the name of God and a united Pakistan," Dacca is today a crushed and frightened city.' These are the immortal lines from Simon Dring's report that defined the Pakistan army's terrible vengeance on the unarmed Bangalis in East Pakistan in March 1971.

It was the journalists who brought the world's attention to Pakistan's atrocities and crimes with their reports even though the Pakistan army tried to keep news of killing its own unarmed population from getting out, first, by preventing the journalists from gathering any information of the killings and destruction and second, by throwing them out of Dacca next day. But a journalist never forgets his duty. And thus the stories came out, first in trickles, then in a torrent.

"In the name of God and a united Pakistan, Dacca is today a crushed and frightened city. After 24 hours of ruthless, cold-blooded shelling by the Pakistan Army, as many as 7,000 people are dead, large areas have been levelled and East Pakistan's fight for independence has been brutally put to an end."

This was the famous intro of the story written by Simon Dring, the 27-year-old reporter of The Daily Telegraph of London that appeared on the March 30, 1971 issue.

Simon and 34 other journalists from the US, Australia, Britain, Canada,, France, Japan and Russia had converged on Dhaka in March 1971, staying at Hotel Intercontinental (now Ruposhi Bangla) to report on the exciting event of a Bangali leader Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman taking over power from the repressing West Pakistanis. The world interest was not so much for the Bangalis as for Pakistan, a strong ally of the US in the global politics of Cold War. The US was pouring in huge military aid to Pakistan in its fight against the spread of communism.

They got more than they had expected as the Pakistan army cracked down on the unarmed civilians on March 25 midnight in history's most horrendous civilian annihilation nicknamed "Operation Searchlight".

Little did the journalists know that something of such monstrosity was waiting for them.

They had been busy covering the Sheikh Mujibur Rahman-Zulfikar Ali Bhutto talks the whole day. At night, as they were relaxing after filing their reports, they heard the ominous sounds of tank guns and machineguns.

The newsmen were baffled. They wanted to know from soldiers posted at the hotel what was happening. The only answer was death threats.

Several journalists went to the 11th floor where Bhutto was staying to ask him if he knew anything about the shooting.

Robert Kaylor of United Press International (UPI) later wrote how Bhutto reacted to the massacre: "There are two of his (Bhutto's) bodyguards carrying assault rifles standing in the hallway (of the hotel's 11th floor). A member of Bhutto's party comes into the hall and says they have no idea what has happened. He says Bhutto is asleep and instructions are to wake him at 7:30 am."

Sydney H Schanberg of the New York Times who was in Dhaka that night later wrote in his report: "Every time newsmen in the hotel asked officers for information, they were rebuffed. All attempts to reach diplomatic missions failed. In one confrontation, a captain grew enraged at a group of newsmen who had walked out the front door to talk to him. He ordered them back into the building and, to their retreating backs, he shouted, "I can handle you. If I can kill my own people, I can kill you."

The journalists were kept confined completely cut off from any information about the genocide. That was a priority of the Pakistan army because it did not want the world to know of the atrocities.

Pakistan was a recipient of US military aid and was apprehensive that if the US came to know how the US supplied weapons had been used to kill civilians then military assistance might stop. Eventually this happened but not until the terrible vengeance of the Pakistan army had turned East Pakistan into a dark land of blood, tears, and laments.

So to keep journalists away from the hotspot, the military ordered all foreign newsmen to leave Dhaka by 6.15pm of March 26.

Reporter John E Woodruff of The Baltimore Sun wrote on March 28 when a reporter inquired about the nature of the "advisory" to leave Dhaka, Major Siddiq Salik, the Pakistan army's public relations officer, said: "Some advice is obligatory."

Schanberg writes: "It was 8:20, just after President Yahya's speech, their convoy of five trucks with soldiers in front and back, left for the airport."

Just before leaving, the lieutenant colonel in charge was asked by a newsman why the foreign press had to leave. "We want you to leave because it would be dangerous for you," he said. "It will be too bloody." All the hotel employees and other foreigners in the hotel believed that once the newsmen left, carnage would begin.

"At the airport, with firing going on in the distance, the newsmen's luggage was rigidly checked and some television film, particularly that of the British Broadcasting Corporation, was confiscated.

On the ride to the airport in a guarded convoy of military trucks, the newsmen saw troops setting fire to the thatched-roof houses of poor Bengalis who live along the road and who are some of the staunchest supporters of the self-rule movement."

The Pakistan army did a full body search of the journalists before they boarded the plane to ensure that the newsmen could not take out any audio or visual documentation of the carnage.

Robert Kaylor filed this report on March 29 from Hong Kong: "I get my customs check and the inspector tells me he is under "special orders" when I tell him that we were already checked in Dacca. He confiscates my notebooks, carbon copies of cables I have filed from Dacca, newspaper clippings and any scraps of paper he can find in my suitcase, including letters from my wife. He then seizes 14 rolls of unexposed film I have in my camera bag and puts everything in brown manila envelopes. When I ask about it, he says it will be sent to me by mail. I ask when, and he shrugs his shoulders. 'Later,' he says. He declines to issue a receipt."

But not all journalists could be rounded up that March 26 night. Simon Dring evaded the army round-up by hiding on the roof of the Intercontinental Hotel and later went around the city to see at first hand the results of the Army's operation.

He was put on a plane two days later, when he was caught, and then he filed his famous report that defined the war in East Pakistan. Michael Laurent, an Associated Press photographer, also evaded arrest for a couple of days, as did Arnold Zeitlin, the Associated Press correspondent, who could avoid the army confinement because he was out dining with friends on the night of March 25.

These reporters and many others continuously reported the genocide in Bangladesh. These reports proved why a free media is so important and how a free media can change the world opinion. Pakistan army-controlled media, which was full of propaganda about "normalcy" prevailing in East Pakistan and that the Pakistan army was on righteous war against "miscreants," failed to convince the world.

Here are some examples of how the western journalists reported the genocide. Schanberg's report "In Dacca, Troops use artillery to halt revolt" published on March 28, 1971 in New York Times gives a vivid description of Pak Army's brutality.

"The Pakistan army is using artillery and heavy machine guns against unarmed East Pakistani civilians to crush the movement for autonomy in this province of 75 million people."

"When the military action began on Thursday night, soldiers, shouting victory slogans, set ablaze large areas in many parts of Dacca after first shooting into the buildings with automatic rifles, machine guns and recoilless rifles."

When the newsmen tried to go outside to find out what was happening, they were forced back in by the army and told they would be shot if they tried to step out of the building. The firing increased around 1pm and 25 minutes later, the phones at the hotel went dead.

Sydney Schanberg said later in an interview with New York Times journalist Gary J Bass, who later wrote The Blood Telegram, the confined journalists watched from the hotel flames from Dacca University, where, Schanberg says, the army seemed to be shooting artillery.

"The trapped reporters watched a Pakistani solider on a jeep that had a mounted machine gun-equipment probably provided by the United States, Schanberg recalled. They started shooting at students coming from the university, up the road about a mile. They were singing patriotic songs in Bengali. And then the army opened up. We couldn't tell when they hit the ground, if they were ducking or killed."

Along the road to the airport, Schanberg saw burned huts and houses. "It was clear they had killed a lot of people."

Laurent in the report of The Times described, "A mass grave had been hastily covered at the Jagannath Hall and 200 students were reported killed in Iqbal Hall. About 20 bodies were still lying in the grounds and the dormitories. Troops are reported to have fired bazookas into the medical college hospital, but the casualty toll was not known."

The most devastating documentation probably came from the NBC television channel of the US which showed a video clip of students being mowed down at Dhaka University that was filmed by a teacher.

All this and many more reports started building the world sentiment against Pakistan. Journalists started asking the State Department press briefings why American weapons are being used against civilians. Even the US Congress started debating the US role in the war. The world opinion overwhelmingly swayed in favour of the Bangalis.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments