Primary school with a difference

Among the low-caste Hindu families of the distant Kachuai Hills in Chittagong's Patiya upazila education has rarely been a priority. Busy with income-earning chores, many children struggle to maintain an interest in school. Yet in more recent years, a new approach to learning has broken ground. Swapnanagar is a primary school with a difference.

“Usual teaching methodology in Bangladesh isn't very practical,” explains Dhrubajyoti Hore, the convenor of the school's committee. “But our students have tough, very practical lives. They have a lot of other work to do and little time for self-study. They don't have anybody at home to help them either. We want lessons to be engaging. School mustn't feel like a burden.”

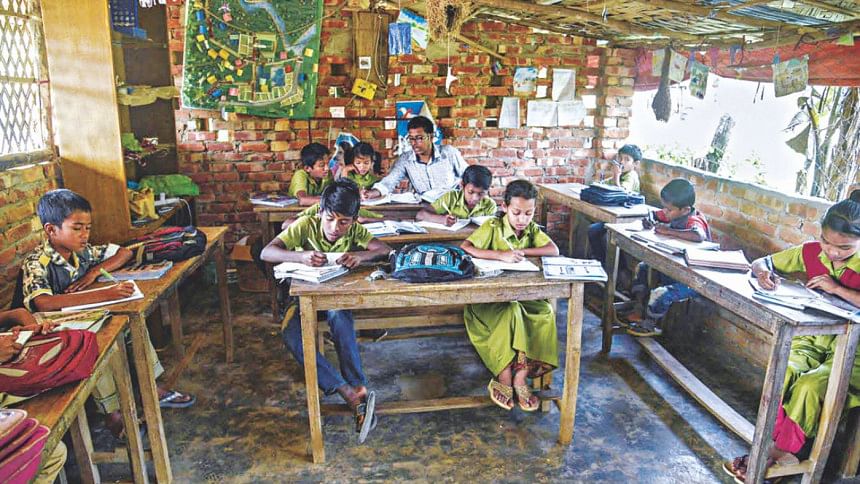

Offering classes one to five, Swapnanagar has developed its own student-centred methodology, which they call 'active learning'. Teachers consider tailoring practices to community reality as paramount.

To visit the school is to find young students, many of whom are descended from tea garden workers, learning the alphabet by sculpting letters from mud. Teamwork is taught by investing responsibility for keeping the school tidy and tending its garden. Books are regularly awarded for achievements, with students encouraged to keep them on a shelf at school. In many homes there isn't any suitable place to store a book. Besides, the shelf is the beginnings of a library.

“Many students don't get enough to eat,” says headmaster Suja Al Mamun. “It's not easy for children to concentrate on an empty stomach so we introduced our 'eggucation' programme. Every student is given an egg before class. Within our budget, we do what we can.”

The school had humble beginnings. In 2004, Higher School Certificate students Rafiqul Islam and Wasim Uddin from Roushanhat in Patiya went to the hills to spend a few leisure hours. They were struck by what they saw: a community deprived of electricity, clean drinking water and sanitation just five kilometres from their homes.

Some days later the friends returned to talk about education. Perhaps the sincerity of the youths' words attracted interest. With community help a dilapidated tea factory was cleaned up, and with just six students Swapnanagar began.

To buy second-hand textbooks, Rafiqul and Wasim raised money and contributed their own, but the school's opening proved premature. Due to budgetary constraints, for the next two years the most that could be done was to ensure local children were enrolled in government schools. It wasn't ideal. Many children didn't find the learning atmosphere appealing and dropped out.

By 2008 the friends were in a position to try again. Swapnanagar reopened in a schoolhouse built by community volunteers. The students who had stopped attending other schools were invited back and Swapnanagar gradually grew to its current size of 103 pupils and nine teachers.

“The biggest challenge is still funding,” says Rafiqul. “Even now we pay the teachers such a pittance that it can't be called a salary. We need another classroom but there aren't funds.”

Despite the limitations the school is making solid progress. Swapnanagar encourages its students to continue into high school. The teachers regularly collect money in local markets to fund scholarships for that purpose, and for the first time two former students have recently completed their Secondary School Certificate exams.

“At most primary schools students fear their teachers,” says one of them, Rekha Das. “At Swapnanagar our teachers were guides and guardians. If it wasn't for them I must've become a day labourer like everybody else in my family. They taught me to dream and I dream of becoming a nurse.”

“Apart from school I don't have many fond childhood memories,” says the other Secondary School Certificate candidate, Rumon Roy. “I'm so proud that I'll be an educated person. I want to work against the problem of 'guide books' for students. I want to rid the country of corruption.”

“Our goal is to eradicate illiteracy in this area,” says Dhrubojyoti Hore. “We hope other schools can work with us in adopting active learning methodology. Perhaps our biggest success is that these days, higher caste families also want their children to study at our school.”

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments