Return of diphtheria rings alarm

There has been no reported diphtheria case in Bangladesh for the last 35 years. But the highly contagious disease, long forgotten in most part of the world due to increased vaccination, has made a sudden comeback.

The first case of the latest outbreak was reported in November in a Rohingya refugee camp in Ukhia, Cox's Bazar.

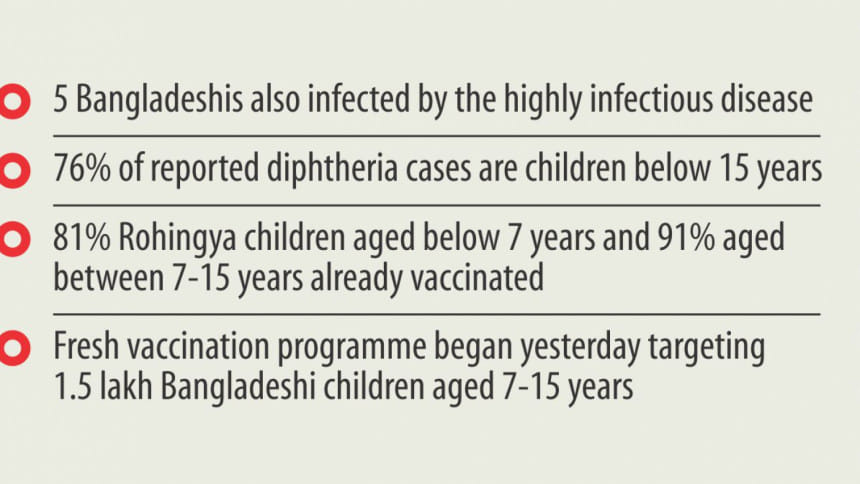

Since then, 27 Rohingya children have died after contracting the bacterial disease. Another 2,700 living in camps in Ukhia and Teknaf have been infected, district Civil Surgeon Abdus Salam told The Daily Star yesterday.

Five Bangladeshi children have also contracted the disease, but are recovering. Aged seven and below, the victims are from Ukhia and they all visited nearby Rohingya camps, he added.

Alarmed, the Bangladesh government and international organisations have started a mass vaccination programme in and around the camps.

Diphtheria transmission occurs from person to person through droplets such as coughing and sneezing and close physical contact. It can be treated by drugs and prevented by vaccine. Symptoms include a thick covering in the back of the throat. It can lead to difficulty in breathing, heart failure, paralysis and even death.

Contacted, Mahmudur Rahman, former director at the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control & Research (IEDCR), said the immediate vaccination programme was the appropriate response to combat the disease.

“According to published data, in Bangladesh the last case of diphtheria in throat was detected in 1976 and on skin in 1983,” he told this paper.

THE OUTBREAK

The first suspected case, in a woman aged about 30, was reported on November 10 at an MSF clinic in a Rohingya camp in Ukhia. It was confirmed through a lab test on December 4.

“I was very surprised when I got that first call from the doctor at the clinic telling me that he had a suspected case of diphtheria,” said Crystal VanLeeuwen, MSF's emergency medical coordinator for Bangladesh.

“'Diphtheria?' I asked, 'Are you sure?' When working in a refugee setting you always have your eyes open for infectious, vaccine-preventable diseases such as tetanus, measles and polio, but diphtheria was not something that was on my radar,” VanLeeuwen said in a statement on December 24.

VACCINATION

On December 12, the government with support from international partners launched a vaccination programme among the Rohingya children to contain the spread of the disease.

Most of the 2,700 who contracted the disease are children aged 5 to 14 and they face high risk of death, officials said.

“We have vaccinated around 1.2 lakh Rohingya children aged below seven and around 1 lakh children aged between 7 and 15,” said Salam, the Cox's Bazar civil surgeon.

Officials expect the vaccination programme will be completed by tomorrow.

Meanwhile, the government yesterday began vaccinating Bangladeshi children living in Ukhia and Teknaf.

Nearly 1 million Rohingya refugees, including more than 6,55,000 who fled Myanmar since August 25 -- live in overcrowded camps spreading over these two upazilas.

Under the programme, 1.5 lakh Bangladeshi children aged between 7 and 15 will be vaccinated in the next two weeks.

CHALLENGES AND WORRY

In the December 24 statement, the MSF said the emergence and the spread of diphtheria show how vulnerable the Rohingya refugees are.

“The majority of them are not vaccinated against any diseases, as they had very limited access to routine healthcare, including vaccinations, back in Myanmar. Diphtheria is transmitted by droplets and spreads easily in the refugee settlements where people live in overcrowded conditions, with shelters squeezed up against each other and sometimes families with up to 10 people living in one very small space.”

Separately, the International Organisation for Migration said key challenges associated with the response to the diphtheria outbreak included low vaccination coverage among the Rohingya population, limited treatment capacity, insufficient global supply of diphtheria anti-toxins (DAT), and necessary isolation, infection prevention and control procedures requiring additional resources.

According to the MSF, there are only less than 5,000 vials of DAT globally. “There is not enough of the medication to treat all of the people in front of you who need it and we are forced to make extremely difficult decisions,” said VanLeeuwen. “It becomes an ethical and equity question.”

Nevertheless, the IOM said it was scaling up its response to the outbreak in a number of fields including risk communication, contact tracing, case management, vaccination, coordination and health system support.

Bangladesh earlier implemented mass vaccination programmes for cholera, polio and measles in Rohingya camps and among the local communities in the area.

COORDINATED HEALTH PACKAGES

The health ministry is also considering providing basic healthcare services to the Rohingya people in a more coordinated and systematic way.

The ministry has already taken up a programme -- Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals Health Intervention Strengthening -- in this regard to protect the refugee population from any disease and thereby safeguard the local population against any outbreak.

Nineteen local and international organisations and development partners will jointly implement the programme, starting this month.

Under this initiative, primary healthcare centres will be set up across the camps -- one for every 20,000 people, said Abul Kalam Azad, director general of the Directorate General of Health Services.

There will be a field hospital for every 2 lakh people where patients will receive indoor treatment except for surgeries, he told The Daily Star.

“Our target is to provide 80 percent medical treatment in the camp area. The rest 20 percent will be given in the upazila health complex and in hospitals in Cox's Bazar and Chittagong,” he said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments