Major breakthrough in lab-grown human embryos

Scientists reported Wednesday they had grown human embryos in the lab for nearly two weeks, an unprecedented feat that promises advances in assisted reproduction, stem-cell therapies and the basic understanding of how human beings form.

Besides opening a window onto the first steps in the creation of an individual, the findings in parallel studies may help explain early miscarriages and why in vitro fertilisation has such a high failure rate.

The research also showed for the first time that newly-forming human embryos can mature beyond a few days outside a mother's womb, something that was previously thought to be impossible.

But the widely hailed results also set science on a collision course with national laws and ethical guidelines, experts cautioned.

Up to now, a so-called "14-day rule" -- which says that human embryos cannot be cultured in the lab for more than two weeks -- has never been seriously challenged simply because no one had succeeded in keeping them alive that long.

In this case, the scientists destroyed the embryos to avoid breaching that limit.

The findings were published in Nature and Nature Cell Biology.

Next to nothing is known about how the small, hollow bundle of cells called a blastocyst -- emerging from a fertilised egg -- attach to the uterus, allowing an embryo to begin to take shape.

"This portion of human development" -- called implantation -- "was a complete black box," said Ali Brivanlou, a professor at The Rockefeller University in New York, and the main architect of the Nature study.

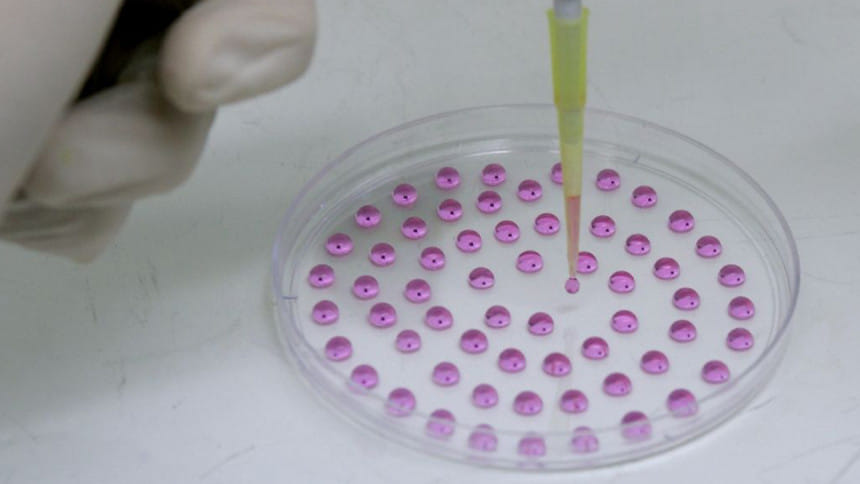

Building on previous work with mice, Brivanlou and colleagues concocted a chemical soup and scaffolding to duplicate this process "in vitro", or in a petri dish.

"We were able to create a system that properly recapitulates what happens during human implantation," said Rockefeller scientist and lead author Alessia Deglincerti.

As hoped, the blastocyst grew, beginning to divide into the different types of cells that eventually give rise to a foetus and its placenta.

But unlike earlier experiments, in which growth has rarely continued beyond seven days, the embryos showed an unexpected ability to self-organise.

"Amazingly, at least up to the first 12 days, development occurred normally in our system in the complete absence of maternal input," Brivanlou said in a statement.

It had long been assumed that this transformation could not persist detached from the mother's uterus.

"Up to now, it has been impossible to study implantation in human embryos," said Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, a professor at the University of Cambridge and an author for both studies.

Slippery slope

"This new technique provides us with a unique opportunity to get a deeper understanding of our own development during these crucial stages and helps us understand what happens, for example, during miscarriage."

The breakthrough is also likely to provide a boost to research on the use of embryonic stem cells to treat certain diseases.

"Only with this knowledge, specifically from human cells, can we control their ability to become cell types useful for drug screening or transplantation," said Gist Croft, also from Rockefeller University.

Scientists not involved in the research hailed the results as a major milestone.

"Both studies clearly demonstrate the incredible intrinsic ability of the embryo to organise itself as it starts to create the body plan -- even in the absence of a mother," said Harry Moore, a professor of reproductive biology at the University of Sheffield in England.

Allan Pacey, also of Sheffield, said they could "revolutionise our understanding of the early events of human embryo development."

Along with most experts commenting on findings, Pacey said ethical concerns are likely overblown.

"It will not open the door to couples being able to grow babies in the laboratory -- this is not the dawn of a Brave New World scenario," he said.

But the scientific community and regulators will still be faced with a decision on whether to lift or extend the 14-day rule, which is law in a dozen countries, and accepted practice in five others, including the United States and China.

Most scientists argue for a loosening of the regulations.

"Given the potential benefits of new research in infertility, improving assisted conception methods, there may be a case in the future for reconsidering this," said Daniel Brison, head of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of Manchester.

But there remains a "slippery slope" problem, commented another expert.

"If we do not use a 14-day rule, what limit will we use?," asked Henry Greely, director of the Center for Law and the Biosciences at the Stanford School of Medicine in California.

"Twelve weeks or so as in many European abortion laws? Viability -- at around 23 weeks -- as in US abortion law?"

"Human development is a seamless process," he added. "But ultimately lines need to be drawn."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments