Scientists 'find cancer's Achilles heel'

Researchers at University College, London have developed a way of finding unique markings within a tumour - its "Achilles heel" - allowing the body to target the disease.

But the personalised method, reported in Science journal, would be expensive and has not yet been tried in patients.

Experts said the idea made sense but could be more complicated in reality.

However, the researchers, whose work was funded by Cancer Research UK, believe their discovery could form the backbone of new treatments and hope to test it in patients within two years.

They believe by analysing the DNA, they'll be able to develop bespoke treatment.

People have tried to steer the immune system to kill tumours before, but cancer vaccines have largely flopped.

One explanation is that they are training the body's own defences to go after the wrong target.

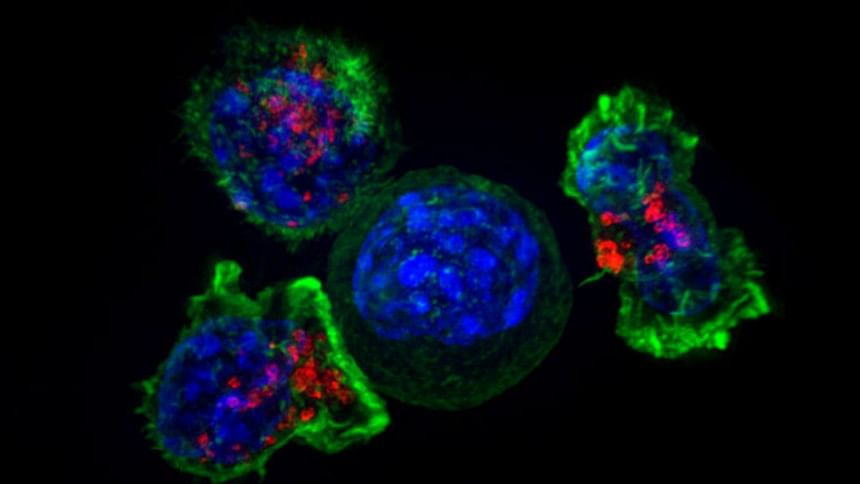

The problem is cancers are not made up of identical cells - they are a heavily mutated, genetic mess and samples at different sites within a tumour can look and behave very differently.

'Exciting'

They grow a bit like a tree with core "trunk" mutations, but then mutations that branch off in all directions. It is known as cancer heterogeneity.

The international study developed a way of discovering the "trunk" mutations that change antigens - the proteins that stick out from the surface of cancer cells.

Professor Charles Swanton, from the UCL Cancer Institute, added: "This is exciting. Now we can prioritise and target tumour antigens that are present in every cell - the Achilles heel of these highly complex cancers.

"This is really fascinating and takes personalised medicine to its absolute limit, where each patient would have a unique, bespoke treatment."

There are two approaches being suggested for targeting the trunk mutations.

The first is to develop cancer vaccines for each patient that train the immune system to spot them.

The second is to "fish" for immune cells that already target those mutations and swell their numbers in the lab, and then put them back into the body.

'Early days'

Dr Marco Gerlinger, from the Institute of Cancer Research, said: "This is a very important step and makes us think about heterogeneity as a problem and why this gives cancer this big advantage.

"Targeting trunk mutations makes sense from many points of view, but it is early days and whether it's that simple, I'm not entirely sure.

"Many cancers are not standing still but they keep evolving constantly. These are moving targets which makes it difficult to get them under control.

"Cancers that can change and evolve could lose the initial antigen or maybe come up with smokescreens of other good antigens so that the immune system gets confused."

Analysis

James Gallagher, health editor, BBC News website

Harnessing the power of the immune system - what's known as immunotherapy - is the most exciting field in cancer and probably in all of medicine right now.

But while that excitement is justified, claims that a cure for cancer is around the corner are not.

Medical research is littered with the graves of hyped treatments that just never worked.

Two decades ago, gene therapy was "hype-central" and we're still waiting for it to transform medicine.

This study demonstrates some spectacular science that furthers understanding of how the immune system and cancer interact.

But this new knowledge has not been used to treat a single patient. There have not even been animal studies. So there is a real risk it will not work.

Even if it does, this is an hugely expensive approach that would need to be customised to every patient in a process that takes more than a year from start to finish.

Some immunotherapy treatments work spectacularly with some patients' cancer disappearing entirely.

They take the brakes off the immune system, freeing it up to fight cancer.

The researchers hope the combination of removing the immune system's brakes and then taking over the steering wheel, will save lives.

Professor Peter Johnson, from Cancer Research UK, said the research had shown "impressive results in the clinic" and although "the technology is complicated and quite recent... once you start doing it the cost will come down".

'Elegant study'

Dr Stefan Symeonides, clinician scientist in experimental cancer medicine at the University of Edinburgh, said designing a personalised vaccine was currently impractical, especially when a patient needed treatment straight away.

But he added that the "very elegant" study did provide a ground-breaking insight into current immunotherapy drugs, which do not yet work for most people.

"It's not just the number of antigens, it's how many of the cancer cells have them," he said.

"This data will be quoted in discussions for years, as we try to understand which patients benefit from immunotherapy drugs, which ones don't, and why, so we can improve those therapies."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments