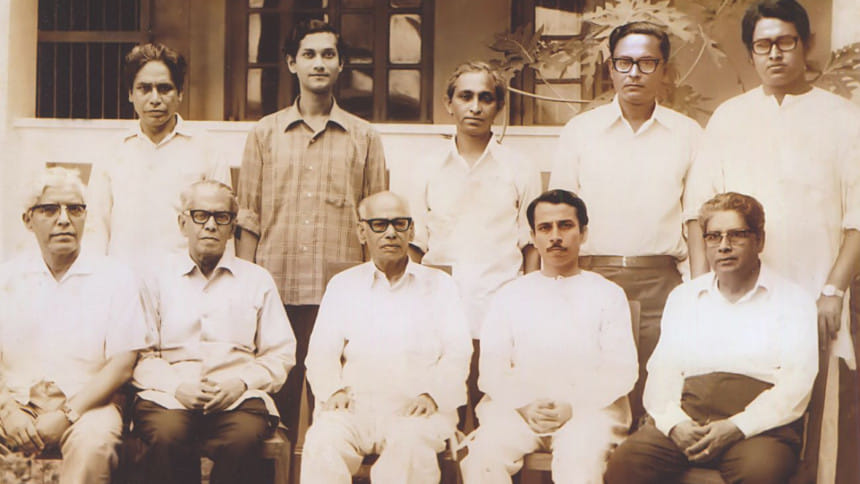

Ajoy Roy, My Father

Ajoy Roy, veteran leftist politician, passed away on October 17, 2016. He had actively taken part in movements opposing the British rule in the Indian sub-continent. He was also one of the organisers of Bangladesh's war of independence. Anindita Roy, his daughter, gives a glimpse into the life of the revolutionary soul.

Charaiveti, charaiveti (Oh travellers, march on!) is part of a Sanskrit hymn about the endless journey towards self-realisation. Charaiveti, charaiveti – these two words became the cardinal mantra for Baba's life. All his life he believed change is inevitable and we need to embrace it. Perhaps, this strong belief helped him to move on with his life with a resolve that was never deterred by the tribulations he encountered – the loss of his parents at an early age, the partition of India in 1947 and finally, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, which led to a great crisis in the Communist Party of Bangladesh. Charaiveti, charaiveti – Baba marched on in his life through all these crises. The crisis after 1991 did not put any dent in his belief in Marxism, which he clearly mentioned in his last interview with Matiur Rahman (published in Pratichinta, July - September 2016). He never moved away from the fundamentals of the materialist conception of history. In the same interview he remarked "the application of the dialectical methods may not be the same in every society." Baba strongly believed in the law of unity and struggle of opposites. For him, the development of society through contradictions and struggle was not merely of pedantic denomination – he could see, feel and drench himself in the struggle. As a Marxist, he saw the fundamental contradiction in history as one between the development of the productive forces on the one hand and the existing social relations of production on the other. He was convinced that the present contradiction of socialised production and individual ownership of means of production should inevitably lead to socialised ownership – a pre-requisite for establishing an egalitarian society.

Ajoy Roy was born on 28 December 1928 at his maternal family home in Ishwargunj, Mymensingh district. He was the first born to his parents Dr. Pramatha Nath Roy and Kalyani Roy. His maternal family, especially his mother, had an immense influence in his life. His mother was his first contact with politics. Kalyani Roy, my grandmother, was influenced by the Swadeshi movement, which started to oppose the British decision to partition Bengal. Baba's maternal and paternal uncles were in prison in Deoli prison camp (Rajasthan, India). Several socialists and communists were detained in Deoli prison. Baba got involved with the left-leaning student federation in Benaras at an early age, when he was in school. After the demise of his parents he returned to Banagram, Kishoreganj with his young siblings. In 1946, he got admission in Haraganga College in Munshiganj and continued working with left-oriented student organisations. He was the joint secretary of the Student Federation in Dhaka district, when Munier Choudhury was the general secretary. In 1948, even before he got his degree, Baba was imprisoned. Thereafter, on several occasions, he was in prison for 15 years and was underground for about 12 years. He completed his M.A. in Economics from Dhaka University in 1964 – from prison. Ajoy Roy was a very bright student; he stood first in most of the exams for which he appeared. The intellectual environment in which he grew up provided him with the analytical ability to delve deep into topics he studied. His maternal grandfather had a library at home and I remember Baba saying that he saw the entire set of Encyclopedia Britannica in his grandfather's library. He was amazed by the intellectual sophistication and the capacity that people had in remote villages in Bangladesh at that time.

Ajoy Roy was part of the presidium of the Communist Party in Mymensingh district until 1973. Then he came to Dhaka and was a presidium member until he formally gave up his membership in1992.

I do not plan to write his biography here as this has already been shared after he left us on 17 October 2016 (some newspapers mentioned he passed away on 19 October 2016, which is incorrect). This is just an attempt to share some obscure moments, which are unique to him. Also, it is an attempt to clear my foggy mind and put words to my sense of loss. However, it would be good to take this opportunity to point out some misconceptions: Ajoy Roy's father, Dr. Pramatha Nath Roy, taught foreign languages at Benaras Hindu University, India. He was never a lawyer as some newspapers have reported.

Baba had a remarkable talent of narrating historical anecdotes. His long-term memory was enviable. During our trip to his favourite city Varanasi, we went to visit the Sarnath Archeological Museum. I still remember the way he explained the differences in art and architecture between the Mauryan, the Kushana and the Gupta periods. During the Gupta period the classical phase of Indian art began. He talked about Baburnama with the same ease when I told him about my visit to Babur's tomb in Kabul, Afghanistan. It was Baba who first told me about Vidyadhar Bhattacharya - the chief architect and city planner of Jaipur - when I visited the Pink City. From him I heard the stories of the Sepoy Mutiny during my Lucknow visit and the stories of resilient Vietnamese during the war when I went to Vietnam for my work. His unique style, captivating narration and, most importantly, the perspective in which he placed these stories left an indelible mark on me.

Baba's friends, colleagues and followers elaborated a lot on his academic, political and intellectual life. It would not be wrong to say that his friends and colleagues know more about his political engagements than we, his children, do. I am not sure why Baba hardly shared his political struggle with us, especially with me, and more so after 1991. It could be that I was too young to understand what he was going through. Also, by then I was away from home, in Santiniketan, for my schooling. It is now that I understand how painful it must have been to experience such a blow. Amidst all these crises, I never saw my father losing his calm and gentle demeanour. His never-ending positivism helped him to move forward and try something new. The result of this effort was establishment of the Sammilito Samajik Andolon and the Samprodayik – Jongibaad Birodhi Mancha. He strongly believed it would be suicidal for Bangladesh to give up secularism and fundamentalism cannot be countered without the participation of masses. The fight against the growing trend and acceleration of fundamentalism cannot be carried out by alienating the general people. He strived to create a platform for a social movement to include people from all walks of life in Bangladesh. He worked relentlessly to achieve that and worked behind the scenes, away from the limelight. He was above mindless materialism and self-promotion, which is now widespread in all spheres of our lives.

I noted a tremendous shift in Baba's way of thinking during the last 15 years. Perhaps, he was always like this and I did not have the time and capacity to understand the depth of his intellect. Since I spent my formative years in Santiniketan, I grew up believing Communists did not understand Tagore at all. I argued with Baba with my juvenile vigour that he was a Communist and so he did not accept Tagore. In an immature way, I told him that Stalin did not allow the publication of Tagore's interview because of his critical assessment of the Communist system. Little did I understand how wrong I was; Tagore never believed in an exclusive political interest and perhaps, Baba's effort behind the Sammilita Samajik Andolon stemmed from that. The other change I noted was his yearning to connect with nature. The routine morning walk around Dhanmondi Lake was partly for health reasons and partly to enjoy whatever nature was available amidst a concrete jungle. This year in January we went to Kolkata. He found the concrete around him suffocating. He wanted to leave Kolkata as soon as possible to breathe some fresh air. He did not share this information with me at that time; I came to know about this through his diary. Maybe his longing for closeness with nature made him decide to go back to his village where he is now sleeping under an open sky. Baba, can you breathe now? Can you see the stars clearly? There is no city light to reduce the visibility of the stars. He has gone back to his roots.

I hardly experienced Baba going through depression. His five-month long illness made him depressed, sometimes. Still, he did not give up fighting because giving up was not in his DNA. He had a factory in his body and in his mind, where positive energy and the strength to fight were produced. At some point, he decided he did not want to fight the inevitable anymore. He chose his time to leave. Before going, he left clear instructions for us. The tubes in his body took away his dignity and maybe, that was more painful for him than the actual physical pain. He did not want us to see him in this condition anymore. So, he took permission from my brother and left in peace. I wish Baba could see the love and respect he received from people from all walks of life.

Baba, you cannot fathom how happy and proud people from your village were to have you back in Banagram, Kishoreganj. You won Baba, you won the hearts and the love of the people of your village, of your country. You wanted to be part of the soil of your village and everyone ensured that you remain with your soil. With this you established a deeper connection for us, with your village. Was this your way of helping us to find our roots? You won Baba, and the winner takes it all. I still cannot believe I do not have the space anymore where I was accepted unconditionally and without any judgment. We had mutual trust and dependence. Now, I need to learn to live in this world without your guidance.

Baba fell sick in May this year and a few days before he had the fever attack, he recited these few lines during one of our weekly telephone calls.

"We look before and after,

And pine for what is not;

Our sincerest laughter,

With some pain is fraught;

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought." (P.B. Shelley)

What a life Baba! Wait for me, I hope to see you at the end of the rainbow.

The writer, daughter of Ajoy Roy, is a Public Health Specialist, working with an international organisation in Geneva, Switzerland.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments