Justice After Nuremberg

When the Nuremberg War Trial began more than 70 years ago, it marked a watershed moment in international law. For the first time, an international tribunal held a trial for the punishment for crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and conspiracy to commit these crimes.

Some of the top leaders of the Third Reich, who took part in either planning, carrying out or participating in the Holocaust and other war crimes, were tried in the military tribunals held by the Allied forces. Many of these principal figures of Nazi Germany—paralysed by the fear of humiliation and imminent death—committed suicide before they could be indicted or executed.

The series of military tribunals and decisions that followed had set the groundwork for the development of international jurisprudence in matters of war crimes, among others, by the United Nations and the creation of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague following the adoption of the Rome Statute on this day—also known as World Day for International Justice—nineteen years ago.

The trials, which began on November 20, 1945, lasted 218 days. Twenty-four Nazi leaders were put on trial by the International Military Tribunal resulting in imprisonments, death sentences and even acquittals. While today the prosecution of the key instigators of one of the most murderous regimes may seem unremarkable, it was, at that time, considered by all accounts radical.

For many Germans back then, it was looked upon as an "act of the winning side" rather than a trial of mass murderers who participated in the systematic state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews and other ethnic groups. During the trials, not a single Nazi in the courtroom pleaded guilty. And despite the distinctiveness and savagery of the Holocaust, the government of the newly-formed Federal Republic of Germany asked for clemency for many of the convicted persons who either had their death sentences turn into prison sentences, were released early, or simply resumed normal life.

Given the historic precedence of the Nuremberg War Trial and the magnitude of the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazis, the proceedings of the trials brought forth many controversial political and legal questions that scholars, jurists, journalists and thinkers have since sought to answer.

Did not the prosecution and conviction of such a small number of Nazi leaders set free thousands others who played an instrumental role in committing genocidal violence? Was this a case of "victors' justice" where the winners assembled in court to prosecute the losers? Why then were leaders of Soviet Russia not being charged with waging war of aggression as a result of their and Nazi Germany's joint invasion of Poland? What have we, more than seven decades later, learnt, if anything, from this landmark in the history of international criminal justice? What relevance do the trials hold today?

***

The Nuremberg trials have often been described as the prosecution of the losers by the winners. And in fact they were. Axis war criminals were being prosecuted while Allied war criminals were not. Four victorious powers—the US, Great Britain, Soviet Union and France—had miraculously set aside all differences and decided to jointly try the key Nazi leaders while the rest would be tried in the countries where they had committed the crimes. The trial of an infinitesimal number of Nazi leaders along with the fact that one side (Allied) of the deadliest military conflict in the world—in which around three percent of the then world population was killed—was completely immune to facing trial for its crimes, have, among many other reasons, shed much doubt on the objectivity of the Nuremberg trials.

But to paint the trials wholly as a case of "victors' justice" (i.e. the victor's hypocrisy and double standards when meting out justice to its own forces versus its enemy) is to describe the trials as black and white—which they're not.

"When, many years ago, I described the totalitarian system and analysed the totalitarian mentality, it was always a 'type,' rather than individuals, I had to deal with, and if you look at the system as a whole, every individual person becomes indeed 'a cog small or big,' in the machinery of terror…."

The truth is, never before had the world witnessed anything like the Holocaust. In the words of German historian Eberhard Jäckel, never before had a state put its full power behind implementing a racist doctrine on such a massive scale that the entirety of German society was involved in carrying out, in some way or the other, institutionalised policies of extermination. So to dismiss the trials outright based on the concept of "victors' justice" is to ignore the symbolic significance of punishing, for the first time, a barbaric, despotic regime for its war crimes. (And let's face it—true "justice" always remains elusive in cases like this. The power here lies in its symbolic meaning: a moral victory.)

The irony is that the British, who were part of the whole mechanism to bring to justice the Nazi criminals, never faced trial for the long list of mass murders committed by the empire on which the sun never set. What price did it pay for causing the famines in India in which anywhere between 12 and 29 million Indians died of starvation as the British Empire exported millions of tonnes of wheat to Britain? Or the hasty partition of India brokered by the British which uprooted millions of Hindus and Muslims from the homes they had lived in for generations?

Almost a quarter-century after partition, the 1971 genocide resulted in the murder of millions of Bangladeshis and rape of hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshi women by the Pakistan Army and its local collaborators. Although the Bangladesh government has successfully brought to justice some of these war criminals and has been very vocal in its commitment to investigate war crimes during the independence war, the silence of the Pakistan government on this issue has so far been deafening. Bangladesh plans to go ahead with cases at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against the 195 war criminals who were handed over to Pakistan as per the tripartite agreement signed by Bangladesh, India and Pakistan and who were never put on trial by Pakistan. Far from issuing a formal apology, the Pakistan government, to this day, continues to deny the atrocities committed under its regime.

Genocide denial is much more complex than we think it is. It's more than just the act of refusing to take responsibility for or minimising the genocide in question. It is, at its core, a form of historical revisionism. And this very denial is enabled through a number of tactics: questioning the statistics; blaming the victim; claiming that the killings don't fit the definition of genocide; questioning the motivations of the accuser; claiming that friendly relations and reconciliation are far more important than "past mistakes", etc. It also prolongs the psychological trauma of families of victims and robs them of the truth that is their memory of the murders of their loved ones.

So while it may have seemed that the world took a collective oath to prevent and punish the crime of genocide in light of the moral failures that allowed the Holocaust to happen (and especially after the Nuremberg trials) the reality was far from it.

Genocides that happened in Bangladesh, Rwanda and Cambodia after the Nuremberg trials are proof that the lessons from the trials had hardly been learnt.

***

Amidst this constant state of denial and rewriting of history by nations afflicted with historical amnesia, the prosecution of the perpetrators of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crime of aggression seems like an increasingly difficult task.

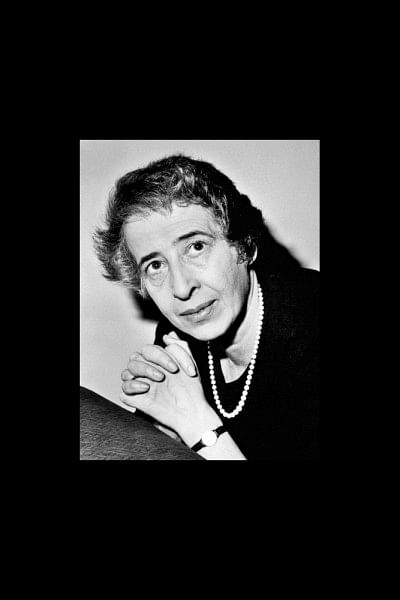

But in the end trials focus on "individual" actors and their actions, do they not? They barely address the system of structural violence underlying these individual actions. This has perhaps best been explained by one of the most important and divisive political thinkers of the twentieth century—Hannah Arendt.

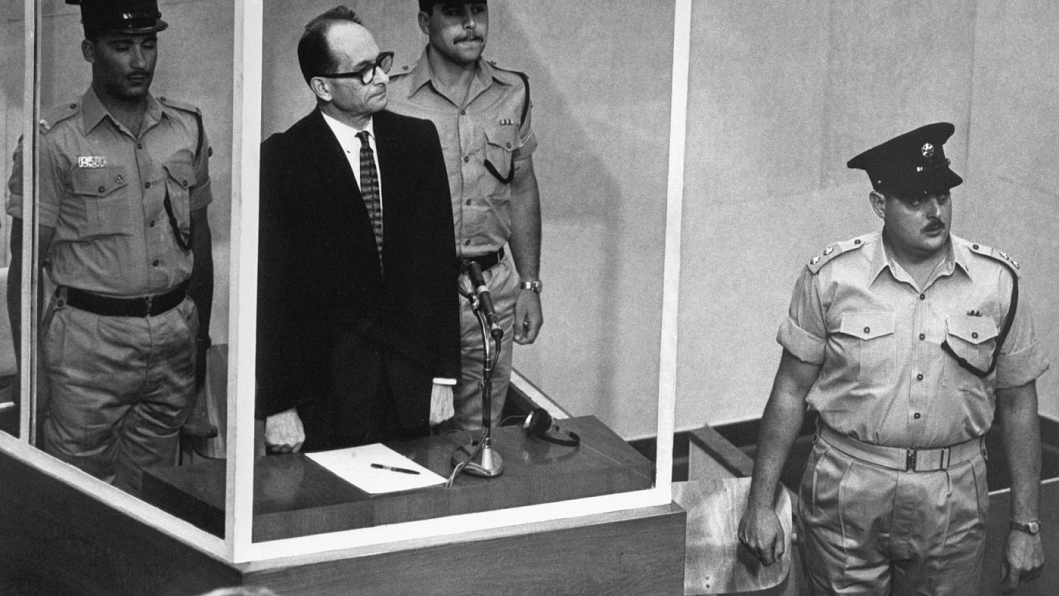

In 1963, The New Yorker published five articles written by Hannah Arendt on the famous trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. Arendt's reporting of the trial which resulted in the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil is—to quote political theorist Corey Robin—one of those rare moments in history where the writer, and not the event itself, has the last word. "The book has become the event, eclipsing the trial itself."

Arendt coined the phrase "the banality of evil", which remains grossly misunderstood to this day, to explain Eichmann's actions. Arendt posited that Eichmann was an ordinary person, just like any of us, who willingly participated in the Holocaust not because of ideological reasons, but because of a combination of careerism and obedience. She believed Eichmann's inability to think for himself and his utterly "thoughtless symbiosis with the Nazi world" and its racist doctrines embodied a "banality of evil." Arendt's words have since been misconstrued to mean that she thought there was nothing exceptional about the Holocaust or that Eichmann didn't actually have evil motives behind committing the horrors. None of these are true. Rather Arendt believed that Eichmann was an individual who was operating within a violent system without questioning it.

After Eichmann in Jerusalem was published, Arendt's life was vexed with both admiration and vilification. Some called her a "self-hating Jew and Nazi lover" while others called her characterisation of Eichmann a "masterpiece". After the publication of her book, she wrote in a letter: "When, many years ago, I described the totalitarian system and analysed the totalitarian mentality, it was always a 'type,' rather than individuals, I had to deal with, and if you look at the system as a whole, every individual person becomes indeed 'a cog small or big,' in the machinery of terror…."

Arendt's astute inquiry into the motives of the perpetrators of the most horrific crimes remains relevant even today. When we ask ourselves, why do mass killings and war crimes continue to this day, despite all the "progress" we thought we have made since the Nuremberg precedent, the answer perhaps lies somewhere much deeper—far from the capacity of any war trial to influence human behaviour—within one of the central themes of Hannah Arendt's life's work: "Human evil originates from a failure not of goodness but of thinking."

Nahela Nowshin is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star.

Comments