Lest we forget

Rana Plaza collapsed on the morning of a hot summer day, on April 24, 2013. Officially, 1100 workers died but the true total is much higher, probably closer to 1400 or 1500. The difference is on account of the 'missing' workers, of the bodies never found or those that lacked documentation as workers. Around 1300 workers died immediately or soon after rescue. While rescue operations continued till May 11, three quarters of the survivors rescued were found in the first two days. Ninety percent of bodies recovered, after their identities were established, were handed over to their families for the last rites. Unidentified bodies were taken care of by the state. The rescue operators, the government and police soon lost interest in searching further for bodies. After May, systematic efforts to explore the site for human remains were discontinued. There were attempts to bulldoze the site, to erase all memory of the crime scene as quickly as possible. While officially endorsed forensic processes were short-lived, street urchins and garbage collectors continued to find evidence of the unfound – skulls and other human remains – at the site for many months on. The Rana Plaza saga is not over, however! This second anniversary is a occasion to remember those who lost their lives, to raise the question of the 'missing', to ensure the rights of the survivors , and to think hard about the crying need for reforms.

In the months following the collapse, families and friends of the recognised victims received sympathy and support from fellow workers, from various organisations, and social workers.

Also the garment manufacturers association (BGMEA), the government, some major garment buyers, and various philanthropists provided financial compensation to some if not all.

True, in some cases some family members of recognised victims obtained help in the form of jobs or other forms of support.

Families of the missing received much sympathy but no support, in the absence of hard, documentary proof, whatsoever.

These families lacked an appointment letter or other documents proving the missing persons' presence there at the time of the collapse.

And the factories at Rana Plaza for that matter did not have precise records of those actually working on the floors at the fateful hour. Having undocumented workers is a common factor on factory floors.

Two of us had had the unhappy experience of conducting field surveys on survivors in the wake of April 24 disaster. We discovered, even then, many workers who lacked proper identity papers and even many who could not identify their employers by name.

Millions of young men and women from rural Bangladesh have migrated to Dhaka and Chittagong in search of jobs at garments and other factories. And thousands keep the tide surging every year, every day.

In many cases, however, a family does not even know exactly where the migrant is working. Perhaps instituting a community register of internal migration will help keep track of undocumented workers in the future.

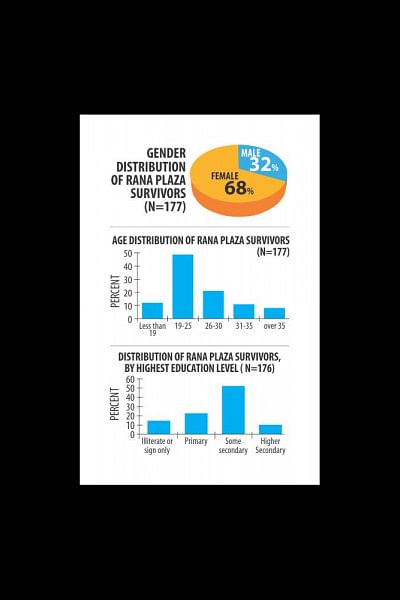

Several of us undertook to interview a sample of seriously injured survivors immediately after the disaster. One of us, Khan, had interviewed 108 victim-survivors immediately after the event at various city and suburban hospitals; its results had been utilised on another occasion. Two others, Huda and Rahman, conducted elaborate interviews with 177 survivors four weeks later. These interviews form the basis of the present article. Our objectives were to understand the surviving workers' perspective in detail. Some results are reported below :

* Rana Plaza victims were young. The average age of women interviewed was 25; the average age of men was 29 years. About 12 percent of the victims were 18 years or less.

* Nearly 90 percent in our sample were under care in one or other of the three hospitals. Centre for Rehabilitation of the Paralysed or CRP is within a few kilometres of Rana Plaza and is renowned for its treatment of spinal cord injuries and providing artificial limbs.

Since spinal cord injury and limb amputation were common among survivors we found one third of our sample at the CRP, not surprisingly. National Orthopedic Hospital was providing services to 30 percent and Enam Medical College Hospital, an institution which rendered exemplary service, was serving 25 percent. Others were placed in Dhaka Medial Collage Hospital, Combined Military Hospital, Savar, and so on.

* Many survivors did not find a suitable hospital for proper treatment of their injuries. For example, if the spinal injury cases had been treated properly immediately after the injury, it could have prevented much of the permanent disability of the survivors. Most of the spinal cord injury cases were referred to hospitals that did not have much experience in treating such cases. These patients remained in those hospitals unnecessarily for several weeks. Appropriate triage is an important lesson to keep in mind for any future accident of this nature.

* Survivors enjoyed above-average levels of schooling. We found 15 percent of them had no formal schooling; about 22 percent had primary education only; more than half of the survivors had secondary education (Class VI-X); another 10 percent had access to higher secondary or higher level of education.

* The majority we found to be married. About 60 percent of them were recently married and parent of at least one child.

In Spring 2015, we undertook some follow-up interviews. We intend to do more but here are some preliminary results:

* At the time of our initial interviews in 2013, we found that the survivors were highly traumatised. They insisted they would never return to the factory floor again. Two years later, we have found many of them actually returning to the scene or the sector. This is not surprising. The only skills they know are the skills of sewing and knitting and other techniques of garment making.

* Not unlike others (such as Hasanat Alamgir in The Lancet), we too found ample evidence of post-traumatic stress, that is to say 'compulsion to repeat' or 'repetition automatism' as one finds in the Freudian literature, among those who had returned to work.

Some talked of compulsive behaviour while at work. They reported a need to leave their work-space whenever they heard an unexpected loud bang. Actually, even without any such noise, some reported feeling intense anxiety at regular intervals while working.

Some survivors who returned to their former trade were found, after a few days of trial at work, to be less agile, less productive than before. As a result many of them have been unmercifully shown the gate.

Lessons from this tragedy

Responsibility for Rana Plaza obviously lies not with one garment owner or one government agency alone but with many. The government should not have allowed construction of such a building to begin with. Garment manufacturers should be concerned with more than cutting costs and hiring the cheapest labour. Buyers too should be concerned with working conditions in the firms they buy from.

Belatedly there have been some changes, but unfortunately not substantial enough. As mentioned above the need for instituting an independent office to register garment workers on the move at both ends, at the point of origin as well as the pole of the pull, the factory. In case of disasters proper triage of the injured must be ensured. These are modest, not unaffordable reforms. Rana Plaza misfortune should have served as a cause or at least a catalyst for a major reform in industrial safety. And more importantly, we should not forget the victims of the disaster. We must not let the memory of the killed fade in memory.

The government and associations of major garment importers have been talking about standards of factory inspection and reexamination of several thousand buildings housing garment factories. That is a good beginning. International Labor Organization, ILO, has called for better enforcement of safety standards in all factories, and for better provisions enabling workers to organise associations representing their interests. Unfortunately, we are yet to witness the setting up of a national standard of compensation and proper rehabilitation. In high-income countries, worker compensation boards set compensation levels for on-the-job injuries, and the costs of compensation are financed by levies on firms that vary based on the injury record of the firm in question. This provides an incentive to manufacturers to improve their safety record.

We believe that the government has undertaken to prepare a comprehensive amendment of the relevant labour laws. We hope that this will see the light of day pretty soon. Reportedly there are provisions there relating to insurance, safety measures, regulation of worker associations, rules and regulations concerning working conditions in the garments sector. We look forward to what we hope will be a thoroughgoing reform accompanied with a new vigor in enforcement.

The measure of civilisation is found in the way it treats its dead and wounded. Two years have passed since the Rana Plaza disaster. The best we can do for those who died there is not to let their deaths go in vain. Safety of those whose work has created an economic success for Bangladesh must be a prime concern. Four decades ago when Bangladesh was liberated it had no garments sector. Bangladesh is today the world's second largest exporter in the sector. If we can uphold work standards it will not only enhance sustainability but the spirit of liberation as well.

Dr Nazmul Huda is a public health project manager at EngenderHealth Bangladesh office.

Desdemona Khan is an anthropologist at Centre for Asian Arts and Cultures, Dhaka.

Labin Rahman is a research fellow at Fair Future Foundation; working for the follow up of the Rana Plaza survivors.

Dr John Richards is a professor in the public policy school at Simon Fraser University in Canada.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments