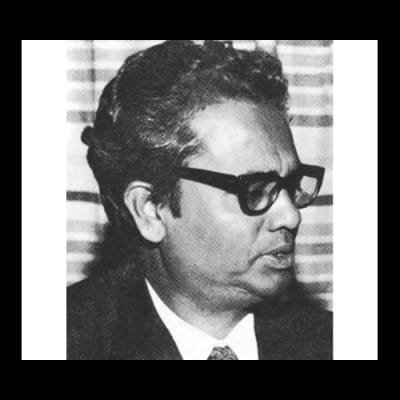

Munier Chowdhury: Personal Glimpses

Tomorrow is the 91st birth anniversary of Munier Chowdhury, educationalist, playwright, literary critic and political dissident, who was picked up on December 14, 1971 by local collaborators and later tortured and killed by the Pakistan Army. Asif Munier, his youngest son gives a glimpse of the life of the martyred intellectual.

Little did anyone know that this apparently quiet but naughty little dark boy would one day become a gifted playwright, teacher, mesmerizing speaker, originator of the Bengali keyboard, a language movement activist, a left political activist and a martyr. That is Munier Chowdhury for you.

But even as a child, he was witty enough to show signs of a great man in the making. Whoever in his family wrote a memoir, never forgot to provide examples of Munier Chowdhury's wits from an early age. His mother wrote in her diary, when Munier was two and a half years old, one afternoon the mother suddenly saw the son walking back and forth in the balcony, head down, hands folded behind, sniffing and mumbling something. She went closer and heard him mumble 'I have made a great mistake, I have made a great mistake' (bhool koira falaisi, is what my grandmother wrote). On inquiry she found out what the kid did – he took out the stopper for the water reservoir and could not put it back on as the water was quickly draining out. As a teenager, Munier loved watching good English movies in the movie theatre. Once he tried out an action scene for real, punching into a glass window and inevitably getting blood on his hands – wrote Kabir Chowdhury in his memoir. Ferdousi, (Ferdousi Mojumdar) his younger sister wrote that because Munier never liked taking a nap in the afternoon as a child, he one afternoon closed his eyes but still was shaking his legs. His mother asked why he was not trying to sleep and Munier's answer was – you told me to close my eyes, but you did not say I could not shake my legs.

Even by the age of 46 until he disappeared, he had achieved so much that it is hardly possible to find anyone these days who can achieve such in their entire lifetime of 60 or 70 years.

Darul Afia, the old house that Munier Chowdhury lived and grew up in – used to hold a lot of memories. The house had been named after my grandmother, whose name was Umme Kabir Afia Begum. This is the house where Munier Chowdhury spent his childhood, running through its long balcony on two floors and green-mud red lawn. This is the house where on the first floor balcony he sat amongst brothers and sisters, and read out from his new writings when his creativity flowed. It was the same house he brought my mother in, even though not very welcomed. It is the very same Darul Afia from where he was picked up by the Rajakar Choudhury Mueen Uddin and his peers.

To all the 31 children of all the 14 brothers and sisters belonging to Darul Afia, life revolved around this house since childhood. The light yellow tinted two storied old house, with green wooden window panes in the middle of Central Road. The road had been renamed in recent years as Shaheed Munier Chowdhury road. The two Eid days spent at Darul Afia were the two most important days of the year that we the children always looked forward to. Our family had an extra advantage – both the grandparents from my mother's and father's side lived almost next door to each other. So we spent almost the entire day between the two household, among uncles-aunts-cousins on both sides. Whatever age we were, we would hang out together, listen to the stories of our parents as they were growing up, eat together fed by one of the aunts, Pichchi (Ferdousi Majumdar) and take a nap together.

I even have snap shot memories of 1971 in that house, with my father, mother and Mishuk bhaiya. Bhashon bhaiya had already gone to fight the war by that time, before anyone knew. I remember that while the curfew was on and the lights were out in the evening, several families living in the house at the time would huddle up together and lay on the floor of the big rooms of Darul Afia. It was almost like a movie scene, sound effects created with occasional sound of fighter planes and guns rattling.

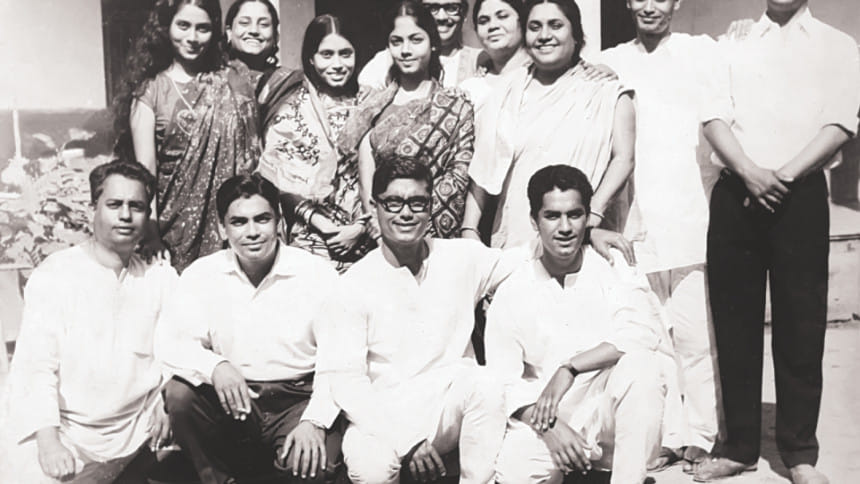

We had a great get together in the early 90s before Darul Afia had been broken down, to be replaced by a boring grey multi-storied apartment. The aunts and cousins organised the dishes, the uncles helped set the tables and clearing the spaces, children making merry. While Mishuk took photographs, I did an amateur video, capturing the laughter where Munier Chowdhury and his siblings grew up in, and we the children grew up with. Our grandparents and some of our parents were not there at that gathering, some others were abroad..but so what. We could still have a wonderful time together, rejoicing in the memory of those not there too.

At least part of the name remains at the apartment on holding number 20 – 'Darul Afia Arcadia'. The walls may not, but the earth beneath holds on to the smell and memories of Afia Begum and Abdul Halim Chowdhury's illustrious children, including Munier Chowdhury.

Munier's wife Lily, my mother, is in her late 80s now. It amazes me how in detail she remembers stories of her life, starting from her childhood back in India before the partition. She reminisces how she met my father, both in their early 20s, and how Munier Chowdhury fell in love with Lily Mirza at first sight. It was in this houe Darul Afia that the two saw each other first. My mother's elder sister was a friend of my father's elder sister. So Moni came to meet Nadera, Lily came with Moni and saw Munier in the house. Lily had not been very impressed with the slightly curly haired, husky voiced young man. Little did she know then that how well this unimpressive looking young man had his way with words. She could have never imagined how he would make her proud as a wife of a legendary writer-teacher, or how her life would change forever without the love of her life – in 1971.

Going back to their love story, Munier had never fallen in love like this before, so he used all his charm to woo Lily, to which the lady gave in hopelessly soon enough. They would find sneaking moments between home and Dhaka University classes (one teaching, the other attending) to meet up, and wander around the race course maidan. Visiting the same ground much later, my mother discovered how that memory lane was being transformed into Suhrawardy Park, preserving the greenery, in a city that is becoming more grey than green.

They wrote wonderful love letters to each other, my father more so as the prolific writer, my mother less so as the busy homemaker, with three very diverse sons. We get to get a sneak peak at those love notes, whether on a post card from Germany or from the diary written inside a prison cell. Dear reader, if you are a fan of Bengali love stories, please do dive into the pages of Dinponji-Monponji-Dakghor (D-M-D), a compilation of love letters written in the form of a diary to each other, while my father was in prison. You might have already read how words of romance flow from the pen of Munier Chowdhury, whether through Ibrahim Kardi or Zohra in Roktakto Prantor, or from Sohrab to Mina in Chithi.

But D-M-D really takes the cake, a candid inner soul of two lovers in their 20s, in Dhaka of the 1940s. It is like the Tumhari Amrita of Bengal, but seemingly much more real for us in Bangladesh. Tumhari Amrita was an indian play by Javed Siddqui, brought to life wonderfully through play reading by none other than Shabana Azmi and Farooq Sheikh in the 1990s.

One must also have the recent stage production Munier Chowdhury by Ongona Theatre – in their bucket list, if one wants a quick one and a half hour tour into MC's life. The feeling at the premiere this November felt like the production could have been better, but the commitment for encapsulating such a larger than life person into a play is praiseworthy. I am sure as they mature with the dialogues and the plot, it will be much more enjoyable. Other theatre practitioners may also follow their footsteps to have a shot at creative work on Munier Chowdhury.

Years later, the Abdul Halim Chowdhury clan still finds moments to be together once in a while, every year, without fail. Darul Afia is no longer there in its real form for us to meet, so we meet in someone else's home which we transform into Darul Afia. We move on with the times, using Darul Afia email group and Darul Afia page on facebook – to meet and interact. The vivid memories of our parents live through the stories that the living aunts and uncles keep sharing with is, and we share it with the next generation after us.

Whether it is a family wedding, one of them visiting from US or an outing organised by the most organised, it's the same old 'ha-ha' and 'hi-hi', the family jokes and the affectionate company. The faces have changed, grown up or grey. Many faces missing, replaced by new and younger ones. Manik, Munier, Hena, Nasir, Johur, Kona, Monju, Dilu, Rusho have all gone. But their photographs and memories remain. Also still remain the rest of the siblings - Shelly, Ferdousi, Banu, Khoka and Rahela. Also are there the scores of children and grandchildren, carrying on the legacy of Darul Afia. The legacy that is of the Khan Bahadur Sa'ab Abdul Halim Chowdhury and the rotnogorva mother Afia Begum. The legacy of Munier Chowdhury, Kabir Chowdhury and Nadera Begum.

Happy Birthday Baba, who is living in my soul, and through Darul Afia stories. Click.

The writer is the youngest son of martyred Professor Munier Chowdhury & member of the Darul Afia clan

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments