Bangabandhu: the architect of Bangladesh's foreign policy

We celebrate 2020 as "Mujib Borsho", to mark our Founding Father Bangabandhu's birth centenary; we also mourn, and reflect on, his brutal assassination 46 years ago on the 15th August 1975. This year also appears to have triggered off a "media war" in our region engaged on the direction of our foreign policy, and some angst on its direction. It would be very moot to revisit the foundations of our policy that were laid down by the Father of the Nation during his lifetime and to reflect on whether we have followed or deviated from them.

A fundamental dictum in foreign policy formulation and analysis is unquestionably this: each country, as a sovereign, independent nation-state, contextualises its every move or action within the overall rubric of preservation and advancement of its own national interest. Therefore, each party, in any bilateral relationship must acknowledge and be fully conscious of these mutual constraints, and also respect "where the other party is coming from". It takes two to tango, as they say, and if each dancer in performing this very difficult and complex choreography is not in tune, innately, with the partner, a misstep or miscue would end in serious accident or injury to one or both.

Bangabandhu was very much, like all individuals, a product of his time and space, and his political and worldviews were shaped by his own associations with his own family, community, mentors and the larger society that he was born into. This is very honestly reflected in his "Unfinished Memoirs" and other writings published posthumously. While he became very deeply involved in the larger movement for Indian independence from colonial rule, he also espoused the cause of democratic federalism like his political mentor, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. Suhrawardy, also representing Bengal at the 1940 All-India Muslim League Conference at Lahore Conference, had passionately argued for an united Bengal and that "each of the provinces in the Muslim majority areas should be accepted as a sovereign state and each province should be given the right to choose its own constitution or enter into a commonwealth with the neighbouring province or provinces". It is another matter that between 1940 and 1947, many factors in the evolving dynamics changed rapidly; and that Jinnah was singularly unsympathetic to the idea of Calcutta being included as a part of East Bengal or to the request of the Muslim (Rohingya) leadership of then Arakan province of Burma (now Rakhine state of Myanmar), then also part of Imperial Britain's colonised India and an integral part of their Bengal Presidency, and rebuffed brusquely to these being included as a part of the new state of East Bengal-East Pakistan at Partition.

Bangabandhu was also acutely aware of the stark reality, that Bangladesh was born in the midst of not only a very deeply divided subcontinent but also a very extremely divided world, and that states do not live or survive in isolation. They are all part of a greater comity of nations. Bangladesh's birth was after all midwifed, and its politics nurtured, so to say, by the Cold War. He was better aware than most that his newly independent nation-state had to navigate through treacherous waters and numerous hidden shoals that lay ahead in its course to viable consolidation.

A parsing of his speeches since his return to Bangladesh in January 1972 following his long incarceration by the brutalising military authority in Pakistan during 1971, and indeed his first actions immediately on his release even before he left the soil of his incarceration, all are very clear reflections of this. While he was flown to London at his request rather than to any other third country in an aircraft of his Pakistani captors, from London he deliberately opted to fly in a British aircraft to his beloved Bangladesh than on an Indian plane that was also on standby. Immediately on his return, when the future of the new-born state of Bangladesh was still in ICU and his own law and order and defence forces largely not organised and still vulnerable, he also requested Mrs. Gandhi to withdraw all Indian forces immediately from Bangladesh. These were not merely symbolic but real assertions of his and Bangladesh's sovereign independence.

As a very young director (personnel) in 1973 in the fledgling foreign ministry, I was also the ex-officio 'rapporteur' at the senior officers' meetings that the Bangladesh foreign secretary held once every week with his senior-most officers (additional and joint secretaries only), at which Bangladesh's foreign policy options and actions were discussed, formulated and planned, and actions evaluated. I learnt how clear and unambiguous Bangabandhu's directions were to his foreign secretary: on India, we were deeply grateful for all Indian assistance in our struggle for liberation and independence but safeguarding our national interest and sovereign independence came first. We would not sacrifice our national interest an iota. Our actions in those early years, riding on the back of his personal charisma and regional and international stature, on seeking permanent but equitable solutions on all cross-border issues inherited from the Pakistan days, whether on sharing of Ganges waters (as a first step towards holistically addressing all other shared water bodies), demarcation of the land boundaries and the delimitation of our maritime boundaries with India and Myanmar with whom we shared the Bay of Bengal, all were initiated in real earnest in those early years. Bangabandhu was confident that he would be able to arrive at amicable resolution of all these given the personal rapport that he enjoyed with Mrs. Gandhi. I personally believe that he would have achieved all that, had he not been so brutally assassinated in 1975.

His ideas on regional relations were spelt out right at the infancy of our independent state. Immediately after liberation, in a speech at a public reception hosted by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in his honour in Kolkata on February 6, 1972, he had unequivocally asserted that in a world of war and confrontation, "We could live side by side as neighbours and pursue constructive policies for benefit of the people… achievement of peace and stability in this region can be a model for others…."

While building bridges with our immediate neighbour India, he also reached out to the other awakening giant in Asia, China, a country he had visited earlier in the sixties, and where he had been deeply impressed by what he saw. Even though China had sided with Pakistan in the Cold War politics of 1971, and had not recognised Bangladesh diplomatically, he understood only too well that he must make the first move towards a reconciliation, sooner rather than later, particularly since China as member of the UNSC held the key to our admission in the UN. He dispatched Ambassador K. M. Kaiser (who as Pakistan's ambassador to China earlier had developed very close personal rapport with the top Chinese leadership), early in 1972 to convey a personal message to them. This quiet diplomacy was sustained throughout Bangabandhu's life. He also understood only too well that he must reach out equally to both the superpowers of the day, namely the US and USSR, and build practicable bridges with both.

His commitment to non-alignment stemmed from the deep-rooted belief that it was not in Bangladesh's interest to be caught as a vulnerable nut in the nut-cracker jaws of the contesting powers. He made several allusions to Bangladesh becoming the "Switzerland of the east", not merely in the sense of promoting tourism. I do believe that he understood full well that neutrality entailed not getting enmeshed in the cut-throat rivalries of fiercely contesting great powers, whether between the powers in his immediate neighbourhood (India and China) or the superpowers that dominated a deeply divided world (US-USSR).

As a country with the then second-largest Muslim population globally, after Indonesia, and also considering how initially many, if not most, of these countries, taken in by the Pakistani propaganda of a Hindu-India having deliberately split a Muslim Pakistan apart, were initially hostile to Bangladesh, he recognised the necessity of reaching out to those countries. In 1974, he dispatched delegations led by his foreign minister to several countries considered to be of great political and economic importance. As the first director of the just created Middle East and Africa Desk of the foreign ministry, I had the privilege of being a member of these delegations to Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. We were successful in all but one of these missions – Saudi King Feisal, while ready to offer humanitarian assistance to Bangladesh, refused to accord recognition unless we changed our Constitution to abjure secularism and became an Islamic Republic. Our response to this was polite but firm: the Constitution reflected the will of the entire nation and it could only be changed by the people, not by any government or leaders. Regardless of this initial rebuff, quiet behind-the-scene efforts were sustained throughout Bangabandhu's lifetime.

In 1974, Bangabandhu agreed to the request of a very high-powered OIC delegation to Bangladesh to join the OIC and attend its forthcoming summit in Lahore, but only if Pakistan first formally recognised Bangladesh as a sovereign independent country, and he would be accorded full state honours with the guard of honour with the national anthem being played, and the flag of Bangladesh flown. I also had the rare privilege of being a member of Bangabandhu's official delegation to Egypt, Iraq, UAE and Kuwait and witnessed first-hand how his mesmeric charisma and personality almost miraculously resolved seemingly intractable problems at arriving at a joint position on issues that had seemed insurmountable at senior officials' level till only the day before he met his counterpart.

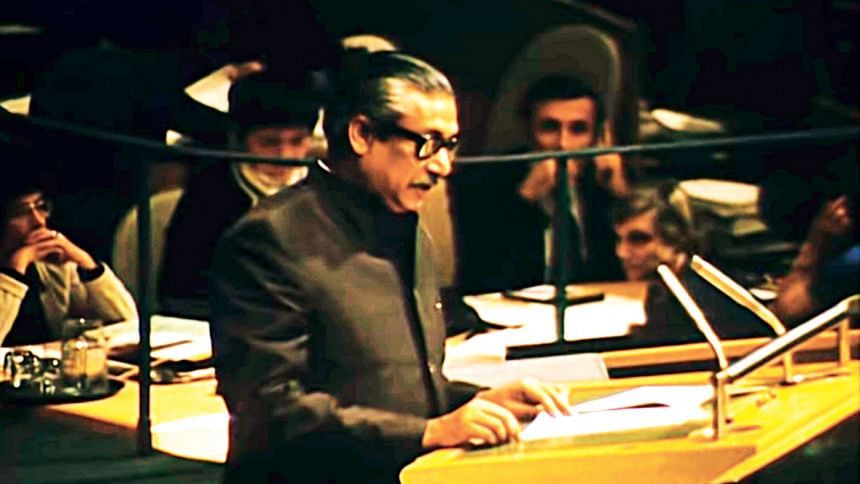

His worldview emanated from his own and his people's collective experiences, in fighting for justice against the denial of equality, fundamental political, economic and cultural rights and particularly the right to self-determination, and of equity in development. One sees this as a repetitive theme in his national and international pronouncements. His speech at the United Nations delivered after our admission as member on September 25, 1974, in my view seminally set the tone and tenor of the underlying principles for our foreign policy. Several points in that speech, with cutting clarity, enunciated his world vision. He alludes repeatedly to the overriding importance of ensuring peace and justice for all peoples in the world, and he reasserts in paragraph 5: "The very struggle of Bangladesh symbolised the universal struggle for peace and justice." He looked beyond the immediate horizon, into the future and in paragraph 7 of that speech he affirms: "While the legacy of injustice from the past has to be liquidated, we are confronted by challenges of the future. Today the nations of the world are faced with critical choices. Upon the wisdom of our choice will depend whether we will move towards a world haunted by the fear of total destruction, threatened by nuclear war, faced with the aggravation of human suffering on horrendous scale, and marked by mass starvation, unemployment and the wretchedness of deepening poverty, or whether we can look forward to a world where human creativity and the great achievements of our age in science and technology will be able to shape a better future free from the threat of nuclear war and based upon sharing of technology and resources on a global scale, so that men everywhere can begin to enjoy the minimal conditions of a decent life." In hindsight, these words were almost prophetic in nature and we could equally relate this assertion to the global situation today.

Deeply aware of the pitfalls of taking sides in a treacherous and dangerous confrontation between two superpowers and their respective alliances in a deeply and bitterly divided world, his penchant for non-alignment and avoiding any display of partisanship that could prove fatal to his fledgling state was clearly enunciated in practically all public statements at every bilateral or international meeting, and encapsulated in that address to the UN: "Bangladesh, from its very inception, adopted a non-aligned foreign policy based upon the principles of peaceful coexistence and of friendship towards all. Our total commitment to peace is born of the realisation that only an environment of peace would enable us to enjoy the fruits of our hard-earned national independence and to mobilise and concentrate all our energies and resources in combating the scourges of poverty, hunger, disease, illiteracy and unemployment (paragraph 12)." Then he affirms: "Peace is an imperative for the survival of mankind; it represents the deepest aspirations of men and women throughout the world. Peace to endure must, however, be peace based upon justice" (paragraph 15).

But the global agenda can only begin from consolidation of friendly relations nearer to his home base. So, he ringingly declares, in paragraph 16: "Consistent with our own total commitment to peace, we have striven to promote the process of reconciliation in our own subcontinent. It was our firm belief that the emergence of Bangladesh would materially contribute towards the creation of a structure of peace and stability in our subcontinent and that the confrontation and strife of the past could be replaced by relations of friendship and co-operation for the welfare of all our peoples. Not only have we developed good-neighbourly relations with our immediate neighbours, India, Burma and Nepal, but we have also striven to turn away from the past and to open a new chapter in our relations with Pakistan." But here he added a caveat. This offer to Pakistan was not unconditional. He asserted, almost immediately in the following sentence: "The just division of the assets of former Pakistan is the other problem which waits urgent solution, Bangladesh for its part was, and remains, ready to move forward towards reconciliation. We expect that, in the overriding interest of the welfare of the peoples of the subcontinent, Pakistan will reciprocate by coming forward to solve these outstanding problems in a spirit of fair play and mutual accommodation so that the process of normalisation can be carried to a successful conclusion." Tragically, that reciprocity never came, and the rest is history.

What underlay his vision of regional cooperation and development? This is neatly encapsulated in paragraph 23, when he comes around back to the central theme of national development within the larger concentric circle of regional aspirations: "In facing the challenge of survival, the resilience and determination of the people is our ultimate strength. Our goal is self-reliance; our chosen path is the united and collective efforts of sharing of resources and technology that could, no doubt, make our task less onerous and reduce the cost in human suffering. But for us in the emerging world, ultimately, we must have faith in ourselves and in our capacity, through the united and concerted efforts of our peoples, to fulfill our destiny and to build for ourselves a better future."

His famously enunciated dictum, that our foreign policy was based on the bedrock of "friendship towards all, and malice towards none," therefore, is not merely a catchy phrase inspired by Lincoln; it flows from his convictions as enunciated above. His illustrious daughter, our current Prime Minister who inherited his mantle, has done well to remain unswerving to these tenets, not merely through words but actions as well, reiterating that our relations with foreign countries flow from the demands of our own national interest; that we shall not develop any relationship with any country that is at the cost of our existing friendship and cooperation with others; that we shall progressively deepen and even expand existing cooperation wherever it advances or consolidates our own development and nation-building efforts towards being self-reliant; and that these relationships that we engage in are not tilted towards anyone, but enable us to form a neutral space where all, even contesting and competitive parties in the region, and beyond, can come together amicably. Everyone around us would do well to try and fathom better where we, as a nation, come from, just as we too shall respect their own visions. The art of arriving at an equilibrium will be dependent on how skillfully we manage these different sets of relationships, hewing to the timeless foundational tenets enunciated by our Father of the Nation.

Tariq Karim is a retired ambassador and currently Senior Fellow at the Independent University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments