Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay and the famine of the fifties

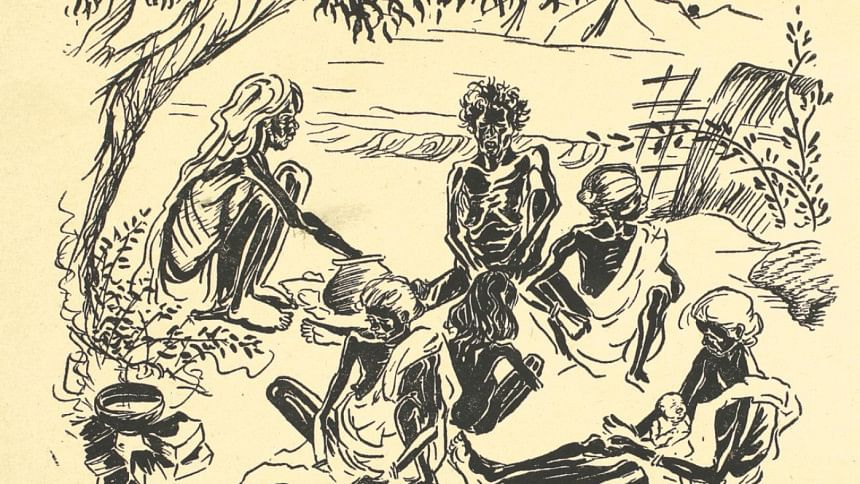

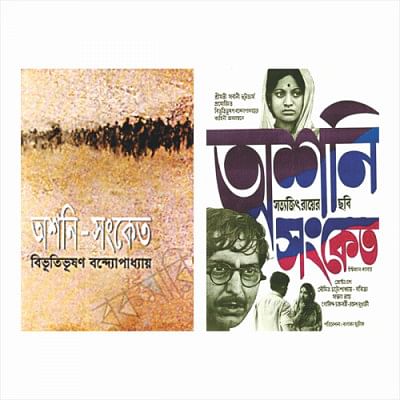

The famine of 1943-46, also known as Panchasher Manwantar (the Famine of the Fifties, referring to Bengali year 1350), almost inevitably reminds one of the drawings of Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin. Known as one of the most devastating human-induced disasters in Indian sub-continental history, the famine is also an integral part of the works of Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay. His best-known work Pother Panchali, subsequently made famous through the Apu Trilogy movies of Satyajit Ray, presents him more in the line of a Wordsworthian and romantic author who softened the harsh poverty and romanticised the scenic beauty of rural Bengal. And yet, he is also the author of the novella Oshoni Shongket, an acute rendering of the famine that occurred during the last days of the British Raj. The plight of Anango Bou, her family and neighbours was later turned into a movie with the same title (English title: Distant Thunder) by Ray again and has been placed among the 1000 best-made movies listed in The New York Times. The drifters and beggars that left their homes and villages and wandered around the country in search of food and work, found their way into Bibhu Babu's work. Many of Bibhutibhushan's short stories too. depict the devastation caused by the famine, its effects on the middle class and the disappearance of agricultural labourers, marginal farmers and share croppers, and artisans like potters and weavers of rural Bengal.

Dr Gideon Polya, an Australian biochemist, called the infamous famine, "a man made holocaust" that struck the Bengal province of British India, which included present day West Bengal, Odisha, Bihar and Bangladesh. According to the Famine Enquiry Commission under Sir John Woodhead, the Great famine of Bengal in 1943 was not caused just by a crop failure and natural disasters, but was largely due to an increase in food demand and economic boom during a wartime situation that saw food prices soar and go beyond the reach of the rura1 poor. Thus, it is estimated that "about 30 percent of one particular labourer class died in the famine." It also contributed to an economic shift that drastically changed the social structure of Bengal. Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay's works delineate the predicament faced by a marginal people and situate them under a light that questions the ethical perspectives of a social system and human responsibility.

Oshoni Shongket portrays the pre-famine rural Bengal where an upper class Brahmin is treated with respect and welcomed in every way if he chooses to settle in the village of the lower-caste Hindus. The reasoning is very simple—the local villagers would not have to look for Brahmins to perform the puja and other rituals that only the upper-caste people are entitled to. An impoverished Brahmin, Gangacharan chooses to settle among the lower caste inhabitants of Notun Ga (new village). Ananga, Gangacharan's wife, an affable and affectionate woman, becomes popular among the village women. Things appear smooth enough until the sudden price hike of rice. And it keeps on soaring. A new kind of struggle of survival begins, a struggle that would see the end of many like Gangacharan who do not own land of their own, but depend on tradition and the generosity of their neighbours. Even if his brush strokes are not half as brash as Manik Bandopadhyay's, Bibhutibhushan also shows painstakingly how the poor were reduced to eating wild berries and plants and women forced into prostitution.

While Oshoni Shongket is recounted by a third person narrator, many of Bandopadhyay's short stories are narrated by a first person speaker providing authenticity to the tales. Regardless of the techniques, however, all the tales bring in the daily life of rural Bengal spent in simplicity and relative ignorance of the vices that would later take over. "Bipod" (Trouble) relates the story of Haju, a teen-aged girl deserted by her husband, who signs up for prostitution during the rough days of the famine. Bandopadhyay describes in somewhat ludicrous and yet sensitive manner how the young woman with a small child initially works at other people's houses and then takes to begging, before finally turning into a sex-worker. The story is narrated from the viewpoint of an elderly man of some social standing who was a childhood playmate of Haju's deceased father. His standing in the story is that of an onlooker, a paternal kind of figure, who wonders if he can help a destitute girl, but fails to do anything substantial.

In "Chaul" (Rice) we come across a destitute wood-cutter who decides to leave his home in the hills to seek better fortune in the city. He is forced to choose the profession of begging for lack of anything else and when the famine becomes fierce, he decides to return to his village. The narrator, again a middle-class observer working in the forest, comes across the vagrant with a small girl-child and takes an interest in them. Some eight months later, he comes across the same wood-cutter at another place seriously injured in an accident. His search for rice had brought him to a dangerous profession of blasting boulders with dynamite. As his life runs its course, the author observes with profound sadness, that he had no time even for his soon-to-be orphaned daughter Thupi.

While in all these Wordsworthian tales there is an element of pathos, there is also that grudging understanding that a few coins or a treat would not solve the problem delineated here. It would require an entire system to elevate these people from destitution. Another point to remember here is that the poor of this land were already living on the margins. As the Famine Inquiry Commission reported, "even before the famine of 1943, at least half of the nearly 46 million in Bengal who depended on agriculture for their livelihood were landless or land-poor labourers under consistent threat of food insecurity, with landholdings barely adequate to provide for the dietary needs of the owner's family" (6). For them it was just a matter of tipping the balance and that is exactly what happened in 1943 and while many of the city-dwellers thrived through economic boom during the war, these folks lost it all.

Dr Polya calls this a "holocaust," and indeed this was a holocaust induced partially by war-time emergency and the government's unwillingness to admit that there was a famine in Bengal. The historian Madhusree Mukherjee blames the British government, which even refused Canadian and American help of relief, for the situation. It is as if the natives of Bengal were expendable, and that the ego of the politicians was more important than the lives of these people. Winston Churchill, the war-time prime minister of Britain, blamed the people of Bengal who, as he said, "bred like rabbits," and that the famine could not be so bad as Gandhi was still alive. Therefore, the narrators that Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay featured at the centre of his tales are the witnesses of this man-made holocaust. And like any other witness to the sufferings of such a holocaust, they ensure that the tales of these wretched and brave ones reach others, and that future generations are aware of the struggles they went through. The author's descriptions of the famine-affected people are not sentimental but drawn with bold strokes. Here he is not the romantic story-teller of Pother Panchali who softens the harsh reality by glorifying poverty:

I stayed with a relative and saw them coming from dusk to late night—-lines of emaciated children and elderly men and women bent with age. They came with blackened utensils in hands and begged for starch from boiled rice....

Little children waited with pans at the narrow drain of Boheragoda boarding school to collect the starch. The starch that fell through the narrow drain of the kitchen. Even rice starch was precious at this point! The headmaster of the school observed that all these poor children would fight with street dogs for the starch and wait for it all day long and at night.

("Chaul")

There is no enforced sense of pathos here, but a bleak description of scenarios much like the drawings of Zainul Abedin of famine-afflicted Bengal. And these stories are not simply about the manner of people dying, but also of people striving to live through the terrifying famine with everything they had. Ananga Bou retains her humanity by sharing with her neighbours the little rice and food she had acquired for her family. She begs her lower caste companion Kapali Bou not to submit to prostitution and promises that they will survive together. Theirs is the tale of many others who lived a meagre life, satisfied with the little they had, but they were also the ones who lost everything including their very lives with the advent of the famine.

They are the homeless ones that Bandopadhyay also identifies in his story, "Bipod":

"The famine of the fifties was over. One could still see one or two skeletons lying by roadsides. The homeless and destitute from the Tripura district left their mark on the face of the earth."

Haju's story is not unfamiliar either— a woman choosing prostitution to feed her family and herself, a tale that is also reflected in Oshoni Shongket through the character of Kapali Bou. These women do not seem much bothered by their lack of morality in the choices they have had to make, although they know that their neighbours would condemn them. The narrator of "Bipod" from his middle-class social standing recognises that Haju had transgressed. But then, he also acts as a witness to her sufferings; and rather than blaming her, he identifies her act as one induced through necessity and finally leading to economic freedom.

The other aspect that is intimately associated with these stories is Bandopadhyay tracing the loss of a class of people—the poor labour class that did not have land, but made their livelihood by small trades, or Brahmins performing the religious rites, or destitute people working at other people's houses or as field hands. These are the people who were gone in the aftermath of the famine. Haju, for example, belongs to a poverty-stricken family that had seen better days. They may never have been actually well-off, but as it is discovered by the narrator, Haju's mother worked as a helping hand as did Haju after returning from her in-laws. And after that even though she begged in the village, she was somewhat protected by the village elders from serious assault; e.g. the narrator himself does so a few times. But, when the famine arrives with all its horrors, she loses that protection too. The villagers who used to give her alms are now irritated at the sight of her. Thupi's father, the woodcutter who dies in the dynamite blast is another example drawn from this dwindling working class that disappeared in the famine. The famine turned many such working class, landless people into vagrants, beggars and prostitutes, and in the end most of them died leaving patches of empty places in the social structure, and deserted thatches in many villages of Bengal.

However, the most significant aspect of the 1943 famine is not death. Famine is degrading for humanity. It can happen to anybody anywhere and it takes away the coverings of civilisation. The streams of suffering humans that are forced to leave their homes in search of food, defecate under the open sky, hold out their pans and plates to strangers for food, and dubbed as animals and nuisances, are humiliating to human dignity. Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay attempts to humanise the terrifying aspects of the famine by showing how it happened and how human beings stand helpless in the face of such disasters. Indeed his work is of relevance and importance for us who dwell in a world that faces similar tribulation dealt out in civil-war and ethnic cleansing.

Sohana Manzoor is Assistant Professor, Department of English & Humanities at ULAB.

Comments