History and the Birangona

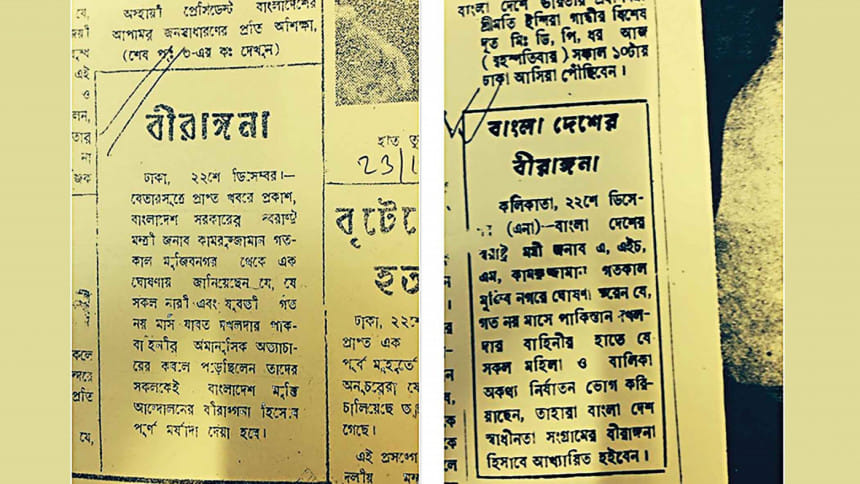

In December 1971, East Pakistan became the independent nation of Bangladesh after a nine-month war with West Pakistan and their local Bengali collaborators. Faced with a huge population of rape survivors, the new Bangladeshi government – six days after the end of the war – publicly designated any woman raped in the war a birangona (a brave or courageous woman; the Bangladeshi state uses the term to mean 'war-heroine') as an attempt to reduce their social ostracism. Even today, the Bangladeshi government's bold, public effort to refer to the women raped during 1971 as birangonas is internationally unprecedented. Yet the term remains unknown to many outside Bangladesh.

Forty years [50 years] after its independence, the issues of genocide and rape during the Liberation War remains unresolved and the Bangladeshi state is seeking to redress these injustices through the war crimes tribunal. In this context, it is important to historicise rape in Bangladesh, especially the reports of wartime sexual violence in the press in the 1990s. The reinscription of personal stories into the national and international domain has tended to obscure the moral complexities of womens' accounts and their experience of dealing with sexual violence.

In 1972, the independent government of Bangladesh set up rehabilitation centres for birangonas, which undertook abortion, put their children up for international adoption, arranged their marriages, trained them in vocational skills, and often ensured them government jobs. Wartime rapes were widely reported in the press from December 1971 until the middle of 1973, after which it was relegated to oblivion in government and journalistic consciousness for 15 years, re-emerging once again in the 1990s. (The issue of wartime rape, however, remained on the public stage as a topic of literary and visual representation – films, plays, photographs – since 1971.) What was missing were testimonial accounts of birangonas and their experiences. In 1992, three birangonas from an impoverished background were photographed in a civil society movement demanding the trial of collaborators. These photographs were published in leading national newspapers. From here, the political trajectory of the birangona assumed a new form as the Bangladeshi press began reporting on wartime rapes again.

A large number of Bangladeshi feminist and human-rights organisations set about documenting testimonies of the birangonas as oral-history accounts, so as to bring to book Bengali men who had collaborated with the Pakistani army in 1971. In the late 1990s, a famous sculptor, Ferdousi Priyobhashini, publicly acknowledged that she had been raped during the war. She emerged as a central protagonist in demanding the setting up of a war crimes tribunal to try collaborators.

Since 2001, a large number of women have come forward acknowledging their experience of wartime rape in 1971. Quite a few changes have taken place in the representation of the public memories of wartime rape since. These changes are part of attempts by left-liberal activists to rethink and rewrite 1971 in Bangladesh. In 2009, the International Crimes Tribunal was set up. One allegation of sexual violence has been testified to in court: in 2012, a woman spoke against one of the accused, Abdul Quader Mollah. (Some journalists have questioned the veracity of her testimony.) Even in the recent Shahbagh movement of 2013, the figure of the birangona was commonly invoked in protest slogans. Thus, despite assumptions of silence in the last 40 [50] years in Bangladesh, there now exists assertions of a public memory of wartime rape through various literary, visual (films, plays, photographs) and testimonial forms, ensuring that the birangona endures as an iconic figure.

In the 15 years of silence between 1975 and 1990, military governments, state accounts and journalistic reports put greater emphasis on the role of freedom fighters during 1971 when memorialising the history of the war. The re-emergence in the 1990s of the narratives of women's wartime-rape arose in the context of numerous developments: the reinstatement of collaborators; the absence of trials of Razakars (collaborators of the Pakistani army), implicated in the killings of intellectuals during the war; rise of fatwas; international reference to Muktijuddho or Liberation War (occurring at the conjuncture of Cold War politics) as a civil war in the international legal language of human rights; the need for the history of the war to be transmitted to the projonmo (younger generations), and hence the lack of acknowledgement of its genocidal birth. All this represented the unresolved, unreconciled history of the nation.

To the call for trial of collaborators was added the need to establish a war crimes tribunal where the Razakars could be tried and an apology demanded from Pakistan. The documentary War Crimes File, made in 1993 in London, traced the war crimes committed by three collaborators who were based in London's East End and added further fuel to the fire. Internationally, the declaration of rape as a war crime in the Beijing session in 1995, the apology by the Japanese government to the "comfort women" (who were abused as sex slaves by the Japanese army around the Second World War), the wartime rapes in Bosnia and Rwanda, the setting up of the International War Crimes Tribunal, spoke profoundly to the Bangladesh situation. Above all, the publication of the two volumes of Nilima Ibrahim's Ami Birangona Bolchi (This is the War Heroine Speaking) in 1994 and 1995, provided personalised accounts of sexual violence against seven women with whom Ibrahim had been in close contact with when she worked in the Women's Rehabilitation Centre in 1972.

This documentation of the history of rape gathered more momentum from 1996 under the new Awami League government led by Sheikh Hasina, as she was seen to embody the spirit of Muktijuddho. In the 1990s, Bangladeshi feminists, journalists and human-rights activists started to document testimonies of 'grassroot' war-heroines through oral histories, so as to provide supporting evidence to enable the trial of the collaborators. As a result, one would find the frequent presence of portraits and narratives of 'newly discovered' war-heroines in newspapers in the 1990s.

One of the post-event traumas that human-rights advocates wrote into the story of birangonas (ironically, in order to create an authentic subjectivity of the war-heroine) was that rape severed women from structures of marriage, kinship and friends. Mapping her horrific trajectory through disruption from social networks, she was constructed as an abnormality. Though activists attempted to narrate individual accounts of birangonas, they could only exemplify or represent the birangona by exaggerating her trauma.

The case of the three women in Enayetpur whose photographs were published in national newspapers without their consent, in the midst of a civil society movement, is well-documented. In the 1990s, an organisation in Dhaka brought together a number of women who had been subject to sexual violence to testify about their experiences. This was a part of a movement undertaken by the left-liberal civil society to demand the trial of Gholam Azam, a Razakar who had been reinstated in Bangladeshi politics. When the photograph of the three women at this event was published on the front page of all leading Bangladeshi newspapers, it became a visual testimony of how women raped during 1971 were still seeking justice. Although they did not speak at the event, the photograph brought the topic of wartime rape back into the Bangladeshi press.

The photograph framed the women in the midst of a crowd – the three of them squatting and huddled together; one of them appears to be cowering in her posture. Two of them are looking down but seem to be aware of the gaze of the crowds around them, the third looks sideways away from the camera. The photograph, depicting the shrinking body language of the three women, is a far cry from the idioms of protestation and heroism suggested by the captions under the photograph. These photographs resulted in not only giving the '200,000 mothers and sisters' a tangible identity with a face and a name, but it showed that they had a village, a family with husband, sons, daughters and in-laws. This photograph was assumed, without any questions asked, to be an important marker of 'empowerment' and 'agency' in the women's movement in Bangladesh, as rural women were seen to be 'rising' against the collaborators of 1971.

As one of the husbands of the women recalled: "Everyone in Enayetpur knew of the ghotona [event, referring to the rapes during 1971] of these women. After the war, we were asked to give the names of our wives in the list as affected, violated women, as we were told this would get us money, house and medical help. Since that time our name has been on the list." Soon after the war, lists of Muktijoddhas and martyrs were made all over Bangladesh. New lists are today compiled under each successive government with new sets of criteria based on local and national patronage, and power politics.

Local leaders blame each other and say, "I thought the women were to be present in a meeting in Dhaka, not to be made witnesses there and their photographs to be publicly splashed in national newspapers." The women were given various assurances to go to Dhaka: medical treatment, jobs and education for their children. But in order to fulfil these promises, they were asked to "cry their own tears" (to quote one of the women), represent their pain, be a birangona and give their 'jobab' in a machine, in a crowded room in front of many people." 'Jobab' meaning 'to reply' in Bengali, also connotes testimony and witness, each indicating a definite oral and verbal activity. One of the birangonas recalled, "It was a feeling of intense shame (shorom) in front of so many people. I felt the ground under my feet was splitting."

This analogy of 'the ground beneath ones feet splitting' is similar to the account in the Hindu epic Ramayana, when Sita asks for the earth to split so that she can be swallowed in when Ram asks her to go through a second Ogniporikkha, or trial by fire. (I am not trying to suggest that the birangona's organising metaphor was necessarily this epical account, though it could be, given the popularity of Ramayana in the rural public culture in Bangladesh.) For her, this phrase is, perhaps, connotative of the intense desire to make oneself physically disappear from the gaze that portrays her as a birangona due to humiliation and shame. It metaphorically highlights the devastating effect of the 'ground under my feet splitting' and the shattering of one's life-world. They told me: "Only we were asked to get up on a truck and give jobab in front of millions of people, including bideshi (white foreigners) who started taking our photographs." The women angrily ask, "Shouldn't you tell us why, where you are taking us?"

The women did not speak, but it was announced that they were making demands for the death sentence of Gholam Azam. Here 'jobab' gave a visual, physical and tangible connotation beyond the statistical anonymity of 200,000 birangonas.

After the event, various individuals from around the village and Dhaka started visiting the women to record their experience of 1971. Assurances of jobs, medical treatment, and education continued through the 1990s. These visits generated scorn (khota) from the villagers towards the women and their families. During the eight months I spent in Enayetpur doing my fieldwork from 1997 to 1998, villagers would say to me, "Ora to haush kore jai nai, e to jor purbok hoyeche; the women didn't go on their own, this was done by force." So when they heard about the rapes in 1971, they had nothing to say and there were no social sanctions against the women because they knew that this violent sexual encounter was forced, a tragedy that could have befallen anyone's family. However, in the 1990s, since the women were seen talking about something that is a public secret in Enayetpur, many villagers deployed sanctions against them. According to the villagers, the rapes and, above all, the women's perceived intentionality of talking about it publicly when there was no possibility of bringing the perpetrators – the Pakistani soldiers – to book, was one of the reasons why the women and their families were subjected to khota. The human-rights activists have portrayed them as being rejected by their husbands, families and communities. The complexities through which these women have lived, given the violence of wartime rape and its innumerable renarrations, remain consigned to oblivion.

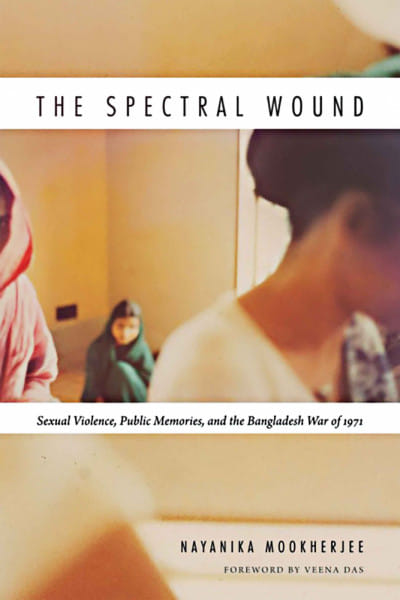

In innumerable instances which I discuss in my book published in 2015, The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public memories and the Bangladesh War of 1971, of documenting and staging testimonies of wartime rape based on oral history projects, the narrative of the birangona is made horrific beyond the details that emerge from the testimonies. She is either identified through the presence of physical markers, like ill health and loss of mental stability or she is constructed as an individual rejected by family and the community. As a result, only the birangona's 'horrific' history of rape is told, not forgotten or silenced, even as the complexities of her life story are occluded from the prevalent discourse of the war.

The significance of oral histories in being a supplement to existing women's history is undoubted. In fact, it is what created the conditions which enabled Bangladeshi women from different background to narrate the violent histories of their 1971 and post-1971 lives. However, while drawing on oral history, researchers need to identify its limitations, especially if they are depending solely on it. I am particularly cautious of how oral history, testimony and memory is often invoked uncritically in retrieving 'untold stories' of a 'real past', and that speaking or having a voice alone is deemed to be healing. Instead, oral histories and national narratives in Bangladesh need to approach the issue of testimonies differently. They need to explore the social life of these testimonies to examine how narratives can be appropriated in various contexts, including by the documenters of these oral histories. Rather than a focus on a linear, voyeuristic narrative of the experience of rape of 1971, testimonial accounts need to focus on the post-conflict trajectory so that small, individual voices are not only connected to the national narratives but their accounts address and connect events of 1971 and the 1990s. Through this, the political functions and the social ramifications of testimonial witnessing within national processes would be highlighted.

At the same time, it is important to ask whether in these instances human-rights narratives require victimhood, and what kind of victim is necessary for that process. In Bangladesh, the authentic victim is marked by trauma, which is determined by a physical condition resulting as a consequence of rape. It also identifies the real war-heroine as one who has no familial and community support. The politics of remembrance here is based on an assumed impact of sexual violence, the consequential trauma and a necessary traumatised post-event life trajectory. Thus the genre of oral history seeks to fit fragments from subaltern voices into a totalising mould whose multiple voices however resist such imposition. Ironically, some activists assume wartime rape has been silenced; on the other hand, the same activists attempt to simplify and erase the complex experiences of the raped women.

All of this should not be read as a negation of the sexual violence of 1971. The point is to move beyond that: instead of a macro, nationalist objective, the representation of the narratives of sexual violence should first and foremost reflect the desires and wishes of the women whose narratives are being highlighted. As a result, I would argue that what constitutes a narrative of rape should not be deductively pre-determined. Instead, it should include the various nuances of experience as expressed by the women. Otherwise a disjunction would arise between the macro narrative and the personal lives which find a place within it. This is one of the ethical dilemmas here. I have attempted to resolve this by straddling two boats: remembering Gayatri Spivak's cautions that research and representation are irreducibly intertwined with politics, power and privilege; and Michael Taussig's challenge to anthropologists to be self critical of their historical and contextual positions, and to speak out against the injustices they encounter in their research 'habitus'. We must tell these narratives not as a horrific, 'traumatic' account, and instead communicate how people fold the violence of wartime rape into everyday social lives.

The writer is the author of The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh War (Duke University Press, 2015). She is a reader of Socio-Cultural Anthropology in Durham University, UK and has published on the anthropology of violence, ethics and aesthetics.

A longer version of this article was published in Himal South Asian on November 9, 2015.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments