Luhani and the national question in the Third International

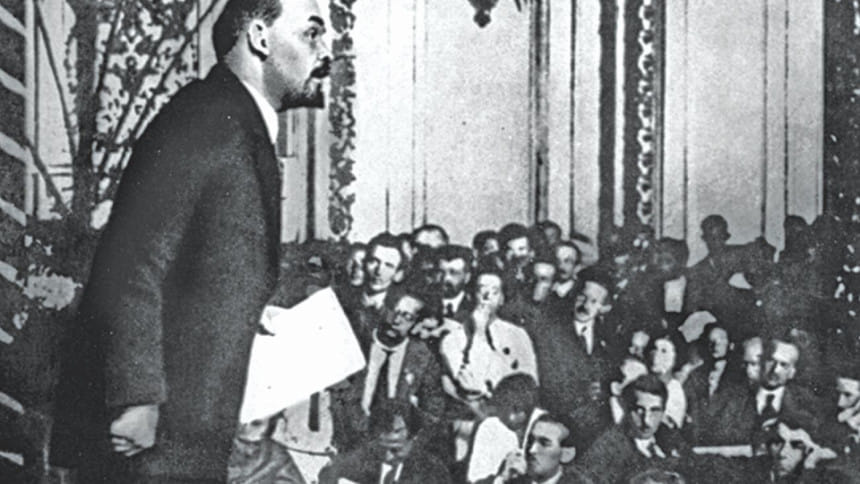

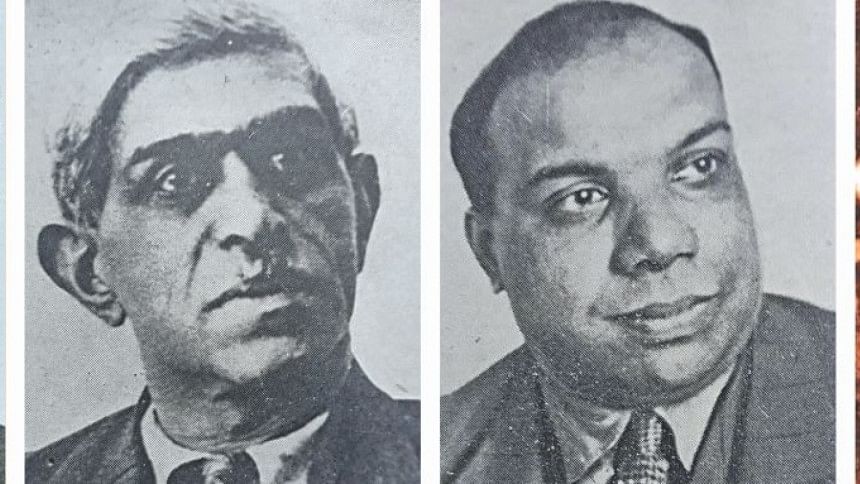

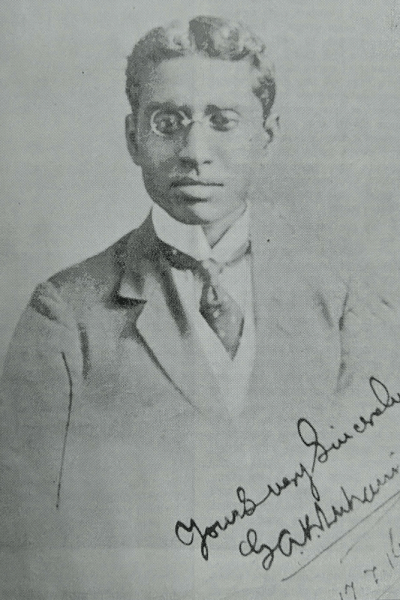

In 1921, a small delegation of Indians reached Moscow from Berlin. The team consisted of Bengali and Marathi émigrés who had earlier been nationalist conspirators or "terrorists" who had regrouped in Berlin, but were now eager to participate in the Third Congress of the Communist International. One of them was Gulam Ambia Khan Luhani, an East Bengali Muslim from Sirajganj.

Born in 1892, Luhani went to London to study law in 1913. The First World War soon broke out and the political tumult brought about radical changes in the outlook of the young student. At first he got in touch with the Berlin Committee that sought to overthrow British rule in India with German support. When Germany lost the war and revolution broke out in Russia, Luhani shifted his allegiance to communism.

In Moscow, the 14-member delegation found Manabendranath Roy, who also had earlier been a nationalist revolutionary and part of the Indo-German conspiracy. Like Luhani and co, Roy also converted to communism in 1917, and was already invited to the Second Congress of the Comintern in 1920. He quickly went on to form a Communist Party of India in Tashkent. The delegation from Berlin of which Luhani was a member was lukewarm towards Roy, as they were worried that he might stand in their way of making overtures to the Soviet leaders. They also wanted the CPI formed in Tashkent to be dissolved. As it worked out, however, they were not not accepted as delegates, but allowed to be present in the Third Congress as visitors. This first encounter foreshadowed the subsequent relations between Luhani and Roy: in later years, Luhani's ideas and actions at their best would have more in common with those of Roy than some of his comrades from Berlin, yet he would often explicitly position himself against Roy.

Luhani, Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, and Pandurag Khankhoje on behalf of the delegation submitted the "Thesis on India and World Revolution" to Lenin and the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI). MN Roy mentions that the thesis was prepared by the Indian comrades to replace the thesis of Roy himself that had been approved in the Second World Congress of Comintern (1920). Luhani drafted the thesis, being the most competent in developing a coherent argument. In the thesis, Luhani observed that while Europe had made transition from feudalism to capitalism, India had a mixture of modes of production. Luhani noted the intersectionality of caste, class, and creed, which were all affected by the structural shift introduced by the colonial situation. As the interaction between these social differences created a complex mix of many-sided antagonisms, a simplistic class-based analysis—holding class as the primary contradiction—was not too practical in the Indian context. His words merit a quotation at length:

"Indian society, like societies everywhere, has been implicitly divided along horizontal lines of cleavage between the exploiting and the exploited classes. But these lines of horizontal cleavage—so sharp and clear—drawn in the industrial West have, in India, been intersected, from the very inception of its history, by exceptionally strong vertical lines of social division and, latterly, of religious antagonism … The sense of social taboo and repugnance felt towards the (Pariahs/hereditary outcastes/numbering one-sixth of the population) even by the members of their own economic class from among the constituent castes of Hindu society has operated to inhibit the growth of any idea of common interest on a class-conscious basis… (The) antithesis between Hinduism and Islam, embodied in their respective religious ideas and social structures has hitherto made the exploited Musalmans and Hindus irresponsive to the necessity of a class-conscious union against a common exploiting bourgeoisie… British Imperialism has not only given a fresh vitality to these causes, but has also in itself been further obstacle to the emergence in India of those conditions which make a revolutionary class-conscious proletariat possible."

While Luhani thought that Lenin was favourable to their thesis, in reality the leader of Russian revolution was sceptical about a new thesis, or about exporting revolution to India. Luhani and co were redirected by the Soviets to work within the existing set up.

In August 1921, Luhani, Chattopadhyaya, and Khankhoje submitted a plan of work in India to the Comintern. It was an ambitious plan: They proposed formation of a 30-member Indian Revolutionary Council to operate from four centres—Russia, Europe, US, and India—to carry out propaganda among Indian emigrants, sailors, soldiers, and people, stressing on Indian troops stationed in North Africa and Southeast Asia as well as Indian migrant workers around the world. Marxist journals were to be published in five principal Indian languages. Cinema would be a key medium to reach the illiterate Indian working classes. The Gadar Party based in the West coast of the US would coordinate the propaganda work. They proposed infiltration of the ongoing Non-Cooperation Movement and the Khilafat Movement in India.

The Comintern, however, decided that no council would be formed. Instead, individual delegates should head out to India for propaganda work. Roy mentions that following the Congress, the Indian delegates, disappointed with the outcomes of the Congress and the meetings, went back to Berlin, save Nalini Gupta and Luhani. Luhani was annoyed with his Berlin comrades and warmed up to Roy. At Roy's advice, he worked for a while in the information department of Comintern.

The Comintern then gave him some money to go to India to carry out agitational work. He could however go only up to Berlin, where the British consul detected the communist agitator by his physical deformity, i.e. his lame leg, and blocked his visa to India. After a few more failed attempts to sneak into his motherland, Luhani headed out to Moscow in 1923.

In the meanwhile, the Indian nationalist movement had been going through momentous transformations under the leadership of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. In Paris, Luhani wrote a few articles on Indian affairs. In the article "Gandhi et l'imperialisme britannique", he lavished praise on the way Gandhi, the ascetic and saint in the eyes of the Indian masses, could mobilise the people against the brute military force of the British in the name of moral force to join civil disobedience, shaking the Raj to its core. For Luhani, imagination played a role in political vicissitudes.

In another article, "L'organisation ouvriere aux Indes", he noted that:

"the vertical organization of Indian society in castes still retains a considerable part of its old influence on the mentality of the workers and resists the conception of a clear-cut horizontal social division between the exploited classes on the one hand and the exploiting classes on the other. It is useful to add here a new element of confusion, which consists of the differences of religion. Hence, one sees the Brahmin members of a union opposing the Muslim members for religious reasons".

The revolution in India as desired by Luhani or Roy seemed to be still unmoored. Meanwhile, a vast communist movement had developed in China, holding up an instructive model in action to the Indian communists. In 1927, MN Roy, back from China, proposed the "decolonisation" theory, to which Luhani too would subscribe. The key question in China was whether the communists should work together with the nationalist Kuomintung Party. The Shanghai Massacre of 1927 dealt a death blow to the provisional collaboration between the communists and the nationalists.

There was no way to ignore the latest developments. In an article in 1928, Luhani noted that in post-war India, a native capitalist class was developing fast. The Indian Congress being a bourgeois organisation was veering towards an increasingly compromising stance. That year, the Simon Commission was to visit India to consider the future of India. Luhani proposed that there should be a common party uniting workers and peasants, while keeping an avenue of cooperation open with the nationalist bourgeoisie. He saw the Workers and Peasants' Party (WPP) formed in 1925—one of the founding members of which was Kazi Nazrul Islam—as a suitable organisation along with the home-grown Communist Party of India. He advocated formation of a Constituent Assembly in India, while presenting a vehement critique of the position of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB).

There are certain cognitive dissonances within communist culture, as a result of the tension between the need for a common line and the varied situations in the different countries. As the USSR served as the epicentre of action, intra-continental international relations to some extent affected the Russian policy towards the nations colonised by the European nations. There was also the contentious question of "labour aristocracy". The nexus between imperialist capitalist affluence and the development of working class in the metropolises often meant that workers' interests might be pitted against the development of competition at the periphery.

In July/August, 1928, the Sixth Comintern Congress was held. The Sixth Congress Theses on Revolutionary Movement in Colonies and Semi-colonies termed nationalist bourgeois-reformist movements as harmful for nationalist revolutionary movements. It called the proletariat to attain hegemony and be antagonistic to bourgeois-reformists. The Indian delegation suggested the amendment that the proletariat must take time to teach the masses about the counter-revolutionary character of bourgeois-reformist leadership. At this point, Luhani and co still were speaking in their own voice. By 1928, Indian affairs were largely delegated to the CPGB, against the protests of MN Roy and Luhani. An Indian sub-commission would be formed under the CPGB headed by RP Dutt.

1929 was the pivotal point in which the Soviet state decisively dismantled the residues of deliberative democracy in the communist movement. As Leon Trotsky was exiled and Nikolai Bukharin was expelled from the politburo, the same iron fist was applied to the darker-skinned communists hailing from further south. MN Roy became an unsalvageable outcaste. The Soviet leadership adopted the so-called "third period" strategy that calumniated any collaboration with the nationalist bourgeoisie.

Even as this contradicted with Luhani's earlier "thesis" calling for "radicalising" the bourgeoisie under a worker-peasant two class party, in the face of the Stalinist juggernaut, a cowed Luhani recanted his position and tried to sing to the tune of those higher-up. The surrender of intellect lock, stock and barrel however could not save his life. After the execution of his former comrades like Virendranath Chattopadhyaya and Abani Mukherjee in 1937, Luhani too was executed on September 17, 1938 in Moscow.

Luhani can be located in one of the blind alleys or digressions of the international communist movement as well as the nationalist movement of India—though his vision was never actualised. His flexible reorientation of subjective outlook from nationalism to communism, to match with shifts in the objective circumstances points at the unavoidable interstices between constructed ideologies. Yet, the deductive and analogical reasoning framework in a centralised communist movement created disjunctures where there needed to be none, while papering over moral and analytical lacuna. The over-institutionalised, over-centralised apparatus of Comintern in its Stalinist transmogrification crushed or silenced dissenting voices with a magnificent mix of epistemological arrogance and practical tyranny. The subsequent history of nationalism in South Asia shows that some of the insights of Luhani in his twenties were too true to be brushed aside.

T Zami is a researcher on Bengal history. He can be reached at [email protected]

Comments