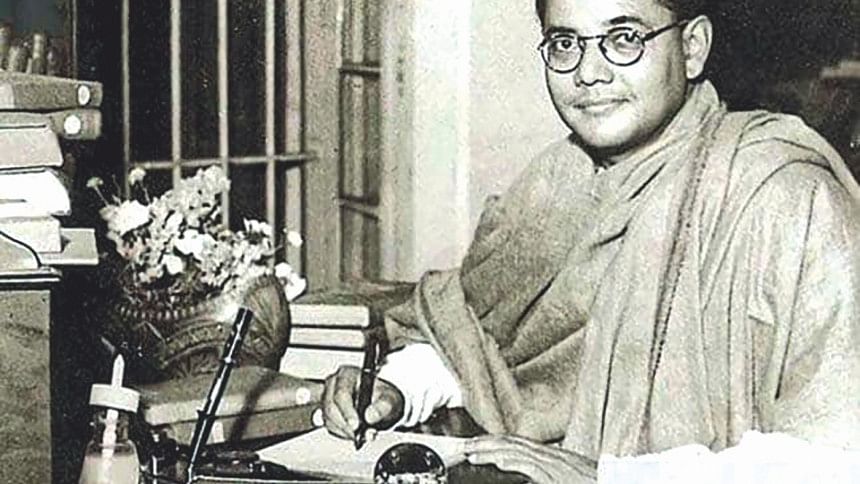

Netaji Subhas Bose in Chattogram

I am enamoured of Netaji. I have been since I was a five-year-old, when I had first listened with wide-eyed wonderment about this legendary hero from the elders in my family. And with each passing year, by leaps and bounds, his stature as an indefatigable Indian nationalist and freedom fighter against the British Raj has kept on growing.

He is now one of the foremost iconic figures in our sub-continental history. He has gradually been resurrected and elevated to a pedestal where he squarely belongs. Sadly, it took the Indian government until 1992, to recognise him as a national hero and confer on him the Bharat Ratna posthumously, the highest civilian honour of the republic of India. However, the award was withdrawn by the Supreme Court of India in 1997, on technical grounds, a great shame for India. I have observed his revered memory being literally worshipped as a semi-divine in Calcutta, West Bengal.

In recent times, Netaji has started to rock the Indian historical, academic and intellectual circles as never before. His legacy continues to haunt us. Sooner or later, the final truth of his supreme sacrifice for India's freedom will place him in the rightful place in the Indian national struggle to achieve political emancipation from the British Raj. Only then will the alternate historical narrative, which has steadily begun to emerge with the declassification of a portion of the Netaji files by the Indian government, substantially rewrite the history of the Indian freedom struggle.

Netaji was so satisfied with the love and care of Nabinchandra's family that when he came back a second time to Chattogram in 1940, after he had resigned as the Congress president, he himself chose to stay again in the same house. In the meantime, he had grown very fond of Urmila Deb because of her selfless devotion to the cause of the motherland.

In 2017, I had written a feature article entitled "Images of Netaji in East Bengal" in The Daily Star. In it I had shared with the readers five rare photographs taken of Netaji's last visit to East Bengal (now Bangladesh) in May 1940, before his "Great Escapade" on January 21, 1941, in disguise from his house on Elgin Road, Calcutta, for Germany via Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. It is also a matter of great pride for us in Bangladesh that Netaji's very last public speech in undivided India was delivered right here in Dhaka on May 20, 1940, under the aegis of the Bengal Political Conference, where he forcefully advocated self-rule for India. In this connection, he had toured Dhaka, Sylhet, Barisal and Chattogram.

However, during my relentless search for a photograph of his visit to Chattogram in 1940, I was unable to find one. It is inconceivable that Netaji did not have Chattogram on his itinerary, the second largest city in East Bengal and a hotbed of the Swadeshi movement, home to the daring Chattogram Armoury raid of 1930, when a lightly armed band of ragtag followers of a valiant Masterda Surya Sen successfully managed to cut Chattogram off from the rest of British India for four days, before the brave sons of the soil were finally overwhelmed by a British military offensive. It had a telling impact on all freedom-loving people throughout India, especially Bengal. Masterda knew that his bold insurrection was doomed to failure and that he and his followers were destined to die in the ensuing shootout with the British forces in their daring attempt and be captured, hanged or jailed. He categorically told his dedicated band of followers the truth. He sincerely believed that their fearless example would be emulated and thus replicated all over British India by similar actions by other freedom-loving groups, whereby, sooner or later, it would exhaust the British Raj and force them to concede India its freedom.

Today, there is no doubt in my mind as to where Netaji got his idea from of an armed rebellion against the Raj. It was undoubtedly from Masterda and the heroic Chattogram Armoury Raid. And that with the advent of WWII, Nazi Germany's European offensive and the Japanese invasion of South East Asia (war on Britain and its capitulation of Malaysia and Singapore) provided him with the golden opportunity he was looking for to embark on his gallant mission with the formation of the Indian National Army (INA) against the Raj. The rest is history.

Early this year, I was pleasantly surprised to get an email from one Tanusree Dey of Chattogram based in the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman. She had read my piece on Netaji and most kindly observed that I had lamented of not finding any information or photograph of Netaji's visit to Chattogram in 1940. She informed me that her family was in possession of two old photographs of Netaji from his two successive visits to Chattogram in 1938 and 1940 and, moreover, that Netaji had actually stayed at her ancestral house in Chattogram. She further wrote to say that Netaji had forged an affectionate relationship with her pishi (paternal aunt), who was an active member of the Swadeshi Andolon (self-rule movement) and was a disciple of Masterda Surya Sen. I was ecstatic.

I requested Tanusree to provide me with some basic information about her erstwhile zamindar family and her family's association with the Swadeshi movement of Masterda Surya Sen and, above all, their close relationship with Netaji Subhas Bose. She readily complied and sent me some rare photographs and documents. I remain beholden to Tanusree for her enthusiasm and help. Here is the remarkable story of Netaji and the Deb Barman zamindar family in brief.

We are used to hearing, viewing (on the internet) and visiting former zamindar houses all over Bangladesh, but never hear of one in the Chattogram region. Well, here is the story of a notable zamindar family of Chattogram. My friend Tanusree's paternal grandfather Nabinchandra Deb Barman went to Burma to seek his fortune in the early 20th century. With hard work and good luck, he soon became a successful merchant dealing in timber, besides other goods. Once he started to prosper, he regularly sent enough money to his dependable older brother, Chandra Deb, an astute man in family matters. Soon Chandra started to invest wisely in landed property in their village home in Rosangiri in Fatikchhari, Chattogram. After buying a considerable amount of property, a zamindari was acquired and a large mansion was built in the village which still stands today known as the Deb-Bari, or the house of the Deb family. The wealthy family also started to buy landed property in Chattogram town and build fine houses in Andarkilla, Khatunganj and the Patharghata areas. The family hosted memorable Puja ceremonies and acquired social prominence through their association with the fine arts, education, cultural and political attainments. They often travelled to Calcutta and maintained a close connection with the premier city of Bengal. As a result, the family became one of the most prominent families of the Chattogram region of the 1930s–40s.

Indian school textbooks are dominated by the post-independence official narrative of the role played by the non-violent movement, that is, the "soft power" approach of the Indian National Congress, while the pivotal role of Netaji and the Indian National Army is dismissed in a few cursory paragraphs.

During this period Chattogram also attained the enviable distinction of becoming the hotbed of anti-colonial agitation and clandestine activities of secret societies in colonial India. The entire environment was such that it was nigh impossible for the educated, politically conscious youth not to be inspired and affected by a towering personality like Masterda Surya Sen and his inspirational activities against the British Raj. Zamindar Nabinchandra himself was a member of the progressive Indian Congress Party. His eldest daughter, Urmila Deb (paternal aunt of Tanusree), got involved with the Swadeshi movement. Being from a rich family, she would often help by secretly donating gold jewellery for the cause of the motherland. Her younger brothers acted as her courier. However, upon being discovered, she was caught by the police, interrogated and jailed. Urmila was released in 1938.

In 1938, Netaji Subhas Bose came to Chattogram on a visit as the president of the Indian National Congress. Zamindar Nabinchandra, himself a member of the Congress Party, was well-known to the chairperson of the Chattogram unit of the Congress Party, Mahim Das. Therefore, it was resolved by all that Netaji should be lodged as a houseguest of Nabinchandra at his Patharghata residence, because of his status and social prestige.

Tanusree's youngest pishi (paternal aunt), Hashi Rai, wrote in her memoir about the spontaneous reception accorded to Netaji on his arrival at the Chattogram railway station and their house. Two fine horses from the zamindar house were garlanded and taken to the railway station in a procession with a band-party by male members of the family along with rank-and-file members of the Congress Party to receive Netaji. The big gate of the zamindar house including the driveway was decked up with a profusion of flowers. As Netaji entered the premises of the zamindar house, riding a handsome horse, the female members of the household welcomed him with rose petals and sang the patriotic song "Bande Mataram". The entire household was refurbished using deshi khadi/khaddar cloth for the occasion in the Gandhian tradition. For curtains, bedsheets, bed spreads and table cloth, only khadi cloth was used. Everyone in the zamindar household including men, women, children and even the house-servants were attired in clothing made of deshi khadi/khaddar to receive Netaji. English goods, clothing especially, was rejected as propounded by the patriotic Swadeshi movement.

It must have been a proud moment for the host family when Netaji entered the house and admiringly observed it all. In those days, when most zamindar families were given to ostentatious lifestyles, the Debs were a different lot. They were progressive minded and imbued with a nationalistic fervour. Zamindar Nabinchandra, who was away in Burma at that time, made sure that Netaji's visit to Chattogram and stay at his house went smoothly as planned. Netaji was so satisfied with the love and care of Nabinchandra's family that when he came back a second time to Chattogram in 1940, after he had resigned as the Congress president, he himself chose to stay again in the same house. In the meantime, he had grown very fond of Urmila Deb because of her selfless devotion to the cause of the motherland. They kept up an endearing correspondence between them. I have been fortunate to read the warm letters of Netaji written to Urmila between 1938 and 1940, from his Elgin Road house in Calcutta and his ancestral home in Cuttack.

Meanwhile, in 1939 Urmila Deb got married to a revolutionary, Subodh Bal, a comrade of Masterda Surya Sen who fought in the battle of the Jalalabad Hill, Chattogram, against the British forces in 1930. He was a cousin of Loknath Bal and Tegor Bal, also comrades of Masterda. It should be recalled here that the teenage Tegor Bal was the first martyr in the Jalalabad battle. It was Tegor's cousin, a close comrade of Masterda, Loknath Bal, who saved the life of a wounded Binod Bihari in the Jalalabad battle by carrying him down the hill at night to safety. When Netaji last visited Chattogram in 1940, Urmila Deb Bal and her husband Subodh Bal were photographed with him (as shown here).

In the groundbreaking, meticulously researched and engrossingly narrated book Bose: An Indian Samurai (2016), the Indian Major-General (retd) GD Bakshi puts forward some pertinently incisive questions and even posits answers on the efficacy of Netaji, the Indian National Army (INA), and its overall impact on the hurried decision of the British to withdraw from India in 1947, granting it freedom. Did India win Independence because of the non-violent movement led by Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Nehru or was it the impact of Subhas Chandra Bose's Indian National Army that made the British panic and leave India? The declassification of the Netaji files has sparked a massive debate on the need to rewrite modern Indian history.

In his book, Major General Bakshi quotes from a conversation between former British Prime Minister Clement Attlee and the then Governor of West Bengal Justice PB Chakraborthy. In 1956, Clement Attlee had come to India and stayed in Kolkata as a guest of the then governor. Attlee was the man who, as leader of the Labour Party and as the British prime minister between 1945 and 1951, had signed off on the decision to grant Independence to India. PB Chakraborthy was at that time the chief justice of the Calcutta High Court and was also serving as the acting governor of West Bengal. The justice wrote, "When I was acting Governor, Lord Attlee, who had given us independence by withdrawing British rule from India, spent two days in the Governor's palace at Calcutta during his tour of India. At that time, I had a prolonged discussion with him regarding the real factors that had led the British to quit India. My direct question to Attlee was that since Gandhi's Quit India movement had tapered off quite some time ago and in 1947 no such new compelling situation had arisen that would necessitate a hasty British departure, why did they have to leave? In his reply Attlee cited several reasons, the principal among them being the erosion of loyalty to the British crown among the Indian army and navy personnel as a result of the military activities of Netaji and the INA." But that's not all. Justice Chakraborthy further added, "Toward the end of our discussion I asked Attlee what was the extent of Gandhi's influence upon the British decision to quit India. Hearing this question, Attlee's lips became twisted in a sarcastic smile as he slowly chewed out the word, m-i-n-i-m-a-l."

The idea behind putting the Netaji files in the public domain is not to undermine in any way the significant contribution of Mahatma Gandhi or Pandit Nehru. However, it is absolutely necessary to start a vigorous debate about the real significance of the role played by Netaji and the Indian National Army. Indian school textbooks are dominated by the post-independence official narrative of the role played by the non-violent movement, that is, the "soft power" approach of the Indian National Congress, while the pivotal role of Netaji and the INA is dismissed in a few cursory paragraphs.

The time has come to revisit modern Indian history and acknowledge the immense contribution of Netaji in helping India win its freedom. A brilliant thinker and strategist, Netaji, went straight for the "jugular vein" of the British Raj, that is, its mainstay, the British Indian Army, which made Pax Britannica possible. He sprung a surprise at the Raj at its most vulnerable period. And he succeeded in doing the impossible. He managed to perform a complete psychological break in the allegiance of the king's and the viceroy's commissioned and non-commissioned Indian officers and troops who had surrendered to the Japanese imperial army in Singapore and Malaysia, by making them break their oath to the British crown and fight for the independence of India by taking on the might of the British Indian army and allied forces in the Eastern theatre of WWII, especially, at the Burma front.

This episode of mass volte-face by Indian officers and men was tantamount to "sacrilege" in the annals of the British Indian army in the modern era. It was an unnerving experience for the Raj. It sent shockwaves throughout the British Indian empire and the corridors of power in London. The British being the "past master" of colonialism knew that their time was nigh up. So they decided to hurriedly quit and run. But not before dealing us a final blow. The wily and "unholy" Anglo-American imperialist combine insidiously managed to successfully split British India into two successor states—India and Pakistan—as a parting gift to its hapless peoples, with the connivance of our own leaders. For starters, read Shameful Flight by Stanley Wolpert. The rest, as they say, is history.

Waqar A Khan is the founder of Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments