Recovering the stories of the Armenians of Asia

Liz Chater, a family history researcher based in the UK, has been working on the Armenian communities in South Asia since 2000. Currently, she is working with the Armenian Church of the Holy Resurrection in Armanitola on the Bangladesh Armenian Heritage Project, which aims to "build the stories, starting from the ground up" of the Armenian communities of Bangladesh and India. In an interview over email with Moyukh Mahtab, she talks of her own heritage, which led her to her research interest, and of her past and present projects.

How did you come to be interested in the Armenian communities of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries in Asia?

My interest in Armenian genealogy in Asia began because of my own family history in India and Dacca [Dhaka]. Like a lot of people here in the UK I was curious about my family's past but actually knew very little about my own family name. My father didn't speak much about his life as a child in India and of course when he passed away it was too late for questions. His brother had been killed in the Second World War at 17 years of age. Their father had also died in the 1940s and I was very young when their mother died, so there simply was no one that I knew of who could tell me about the India connection. My mother gave me a little information and armed with that I travelled to the British Library in London to see what I could discover. I soon realised that there were many people with the name Chater in India and I decided that it would be useful to try and record everyone in the archives with my surname, to try and build a bigger picture. It wasn't long before I found references to my Chater line in Calcutta and Dacca, and that was the spring-board for the journey of a lifetime.

Naturally my research led on to a wider collection of Armenian names. It dawned on me that there was very little information available at the time (around the year 2000) online that was Armenian related. Instinctively, I wanted to try and bring the Armenian family presence in India into a more accessible place to help others who may also be looking for their own Armenian connections in India. I created my website (www.chater-genealogy.com), and started putting general Armenian family history related information on it. Of course when you are researching, you are constantly working backwards and it wasn't long before my enquiries had taken me from the early 20th century, back to the 19th and even earlier to the late-18th centuries and beyond. The further back I went the more engrossed in Armenian family history I became and invariably an answer to a query often created more questions. I began to develop a much deeper interest—a passion for Armenian family history in Asia. I quickly recognised it as one of the less popular aspects of genealogy in India. With only a handful of people who had undertaken research on Armenians and their families in India, it made me even more determined to get involved at roots level. Helping people realise their own personal history, particularly if it contains an Armenian connection, is very important to me.

You mention your search for your family roots in Dhaka and Kolkata. Who were the Chaters here?

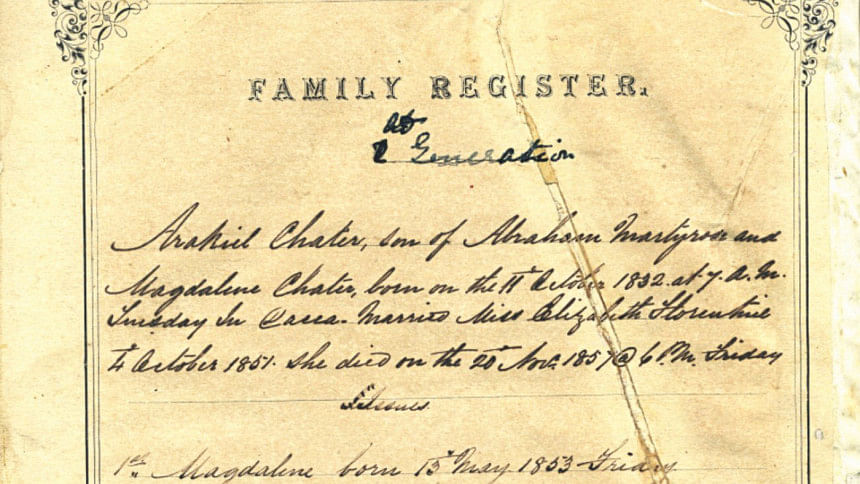

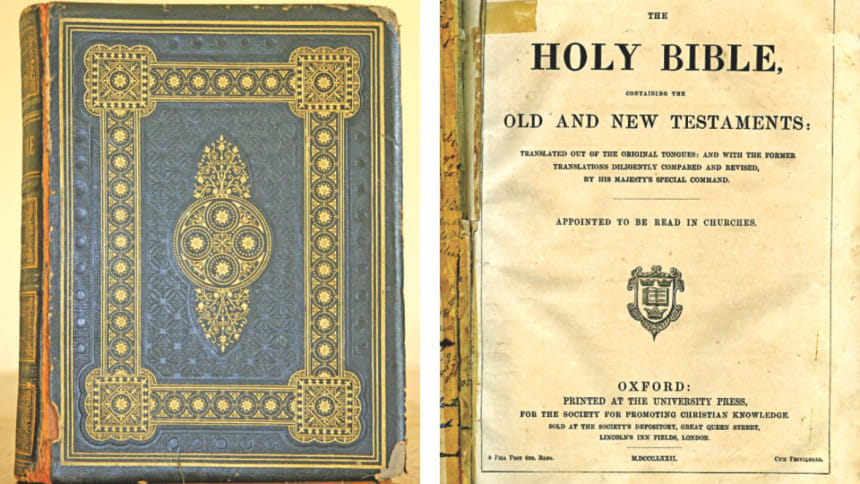

Like many Armenians who settled in Asia, my particular Chater line migrated to India from Persia. I am very fortunate that the family bible of my branch has survived. The earliest entry in the bible is of Arakiel Chater, son of Abraham Martyrose and Magdalene Chater. It states he was born on October 11, 1832 at 7am. Tuesday in Dacca. It goes on to record that Arakiel married Miss Elizabeth Florentine on October 4, 1851 and that she died on November 20, 1857 at 6pm on a Friday. The bible records their children and other generations too.

In the image provided it can be seen that Arakiel and Elizabeth's first child was born on May 13, 1853, whom they named Magdalene. A second child, Elizabeth was born on February 2, 1856 on a Saturday and that she sadly died on the October 5, 1880, although it does not state where.

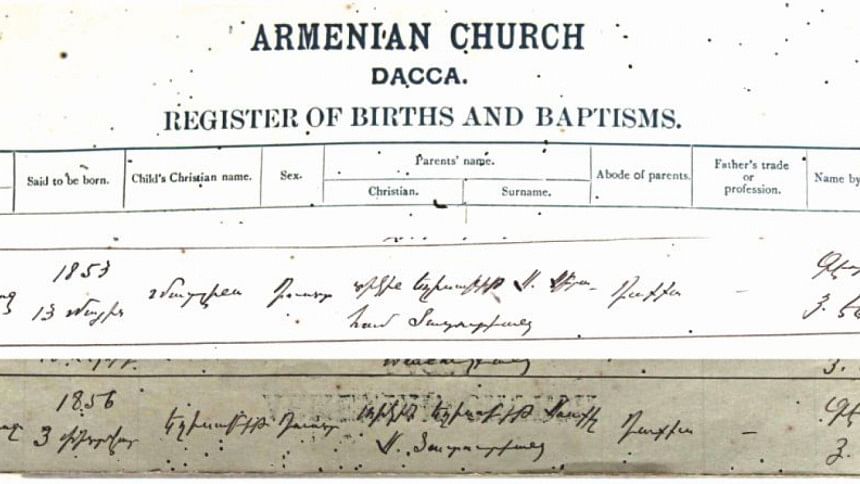

Whilst assisting with the Bangladesh Armenian Heritage Project, what has been exciting for me personally is the process of organising the translating and transcribing of the Church registers. These will eventually be added to the Church website. However, what should be borne in mind is that the Dhaka Church registers are not the original ones. Those seem to have disappeared long ago—the registers the Heritage Project are working with are ones that are much later copies, probably written up in the 1950s or 1960s. Nonetheless, having got them transcribed to English, I have been able to match entries from these records with those entered in my family bible.

Arakiel became a clerk in a Judge's office in Arrah, Mymensingh and Dinajpore. One of his seventeen children was my great grandfather Abraham who became a Post Master working in Port Blair for 10 years, then later Calcutta, Patna and Bankipore. Abraham went on to have at least thirteen children of his own, some of whom did not survive infancy.

I have found the records at the British Library invaluable in my personal research. Besides the baptism, marriage and burial returns, there are numerous other records available for consultation. For example military papers, wills and estate inventories, directories, newspapers, East India records, personal papers, Parliamentary and Treasury papers, Marine Department records such as ships' journals and logs, telegraphic, customs, intelligence and secret records, and much more.

Previously, you have worked on the genealogies of the graves in the Armenian Church in Dhaka. Could you tell us about that project?

I have made several trips to India, particularly Kolkata and during the course of each visit, I made a point of photographing as many Armenian graves and tombstones as I could. On returning home I spent time transcribing the ones in English and uploading them on to my website. The Armenian ones were trickier. I don't speak or read Armenian, but I was fortunate that an Armenian student from Kolkata I met on one of my trips shared my passion for history and with his help, along with the help of one of the Armenian teachers, as well as a number of other people including Professor Sebouh Aslanian, these language-locked stones are once again telling their stories, but this time in English. As I began to make progress with the Armenian tombstones in India, I turned my attention to the ones in Dhaka. I hired a photographer to capture all the stones within the compound of the Armenian Church and once again set about transcribing those I could, and getting professional help for the ones written in Armenian. The Very Reverend Fr Krikor Maksoudian's help was invaluable in this regard.

The Armenian community in Asia has such a rich history, the stones will one day wear away and those people who lay beneath and the stories of their respective lives will be lost and forgotten. If I am able to make a contribution to the preservation of the Armenian presence in Asia then I will be very pleased to play a small part in that.

During a trip to Kolkata in 2005, I was fortunate to be given permission to access one of the many baptism, marriage and burial registers of the Armenian Holy Church of Nazareth. I was able to photograph the very early baptism register entries between 1793–1859. It was of course written in Armenian and I once again had to find a patient and willing helper to translate and transcribe them. It took around two years to complete the register and I was very happy to donate all the work to The Families in British India Society (www.fibis.org) for their growing database of freely available data.

What are you working on currently? How has been the response about the project with the church in Dhaka?

Currently, the Bangladesh Armenian Heritage Project is the main focus of my attention. Over the last few months we have made appeals to anyone who may have had a family connection to the Armenian community of Dhaka at any point during the history of the church. Considering the community's numbers have always been small in Dhaka, both Armen Arslanian (warden of the church) and I are very pleased with the response and contributions that have been made so far. We have been given access to personal family archives, containing a wealth of commercial related documents, photographs and stories.

A completely unexpected side-story that has come to light is of an Armenian musician called Rouben Karakhanian. In 1935 Rouben was in Kolkata visiting the Armenian community there. Travelling on to Dhaka he played a concert in the grounds of the church; the Armenian community enjoyed it immensely. The musician found a most attentive audience and a new friend in a young 22 year old Armenian, Ruben David who was living with his uncle and family at the church who happened to be the resident priest, Reverend Ter Bagrat. The musician gave the young Ruben two signed photographs that became treasured possessions of Ruben's family, and we are delighted that the David family are sharing their archive with the Heritage Project. What is even more extraordinary is that when I was talking through this discovery with Armen, he was rather taken aback, because as a young boy, he remembers meeting the musician 30 years later in the late 1960s at his own home in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Rouben Karakhanian had been invited by Armen's parents to play at their house. Suddenly in 2018, because of his own sequence of life events, Armen, as warden of the Armenian Church in Dhaka found himself remembering a long forgotten memory of his early childhood. Armen says: "Looking at the photograph of Rouben the musician I find myself being reminded of a moment from my very early childhood time that I had no idea would connect me to my future responsibilities of the Armenian Church in Dhaka"—the extraordinary circle of Armenian life, spanning many decades and continents.

As a team, we are pressing forward on the work of the Bangladesh Armenian Heritage Project and continue to appeal for anyone who has or had a family connection to the Armenian community in Dhaka to get in touch with us. This is very much a community driven venture. When we first started this project, we had no idea what material, if any, would be shared with us. A story like that of the David family above just shows how a long forgotten photograph perfectly preserved in an album can be given a breath of life and meaning again.

It seems that with this subject there is a lot that we can still learn about our shared pasts—is there enough research being conducted in this regard?

I haven't come across an Armenian who hasn't got a story to tell but so much history is being lost, forgotten even destroyed. We all have a responsibility to preserve and record what we can as well as help to rediscover the elapsed past. We are fortunate to have Armenian academics dedicating their careers to exactly that.

*The printed version of this article stated that Liz Chater has been working on Aremenian communities since 2010. It has been corrected to 2000.

For more details regarding Liz Chater's research, visit chater-genealogy.com and chater-genealogy.blogspot.com

The Armenian Church would love to hear from anyone with an association to the Armenian families who once lived in this part of the world for their forthcoming research project. To get in touch, email [email protected]

For more on the Armenian Church in Dhaka, visit their Facebook page

Comments