Remembering the Battle of Bhomra

Hell had broken loose. The sky above the Bhomra bund of Satkhira suddenly turned bright, thunderous colours going in all directions. The large contingent of soldiers was in slumber, half asleep, half awake – all voluntary members of the Mukti Bahini who had travelled many miles to confront the brutality of the Pakistani soldiers. The innocent people of Satkhira were being savagely killed and raped by the Pakistan Army.

The Mukti Bahini command post was at the root of a large Shimul tree. Past afternoon, one air bomb from the enemy fire had destroyed the top branch where I was present along with my co-soldiers. Captain Salahuddin of the East Bengal Regiment was in charge of the company. He tumbled up from his drowse, recognising the early dawn attack, and cried out to us: "The enemy is trying to locate our position. Get into trenches and be ready to fire back. Let's teach the heinous Pakistanis a lesson. Joy Bangla."

The plan was to stay camouflaged and probe the space in front so that, when striking was required, it could be achieved smoothly. The area was reverberating with the sound of long-range artillery and cannon shells bursting over our heads.

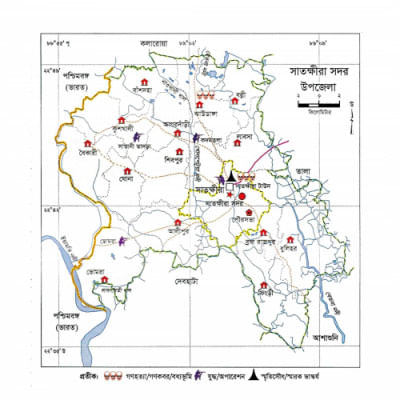

In the meantime, Captain Salahuddin called out for me, his second in command. I was posted out from the South-western command of the Mukti Bahini after the withdrawal from Jhenaidah after its fall. My large group of combat soldiers ranging from all walks of life had trailed me through a circuitous way: moving from Jhenaidah through Chuadanga, Meherpur, Kushtia, via Betai and Benapole onto Gojadanga via the Indian state of Nadia, Kolkata etc. to land on the other side of the Bhomra border. The border outpost of India called Gojadanga finally offered me a space to align my troop for the upcoming struggles.

At the time, my title was Captain Mahbub. I am originally from Jhenaidah and served as the Chief of Police in the subdivision of Jashore District of East Pakistan. I was well known as SDPO Jhenaidah. I organised the resistance in Jhenaidah with my police officers and constables serving in all the six small police stations of the subdivision. I distributed 400 rifles of 0.303 origins from my armoury amongst all from the ordinary rank and file of the local citizenry and my close political friends of the Awami League. I took enthusiasm from their trust upon me to stand against the Pakistani atrocity let loose in Rajarbagh Police Line, Dhaka, Pilkhana of East Pakistan Rifles (EPR), Iqbal Hall of Dhaka University and so on. Bangabandhu's call for independence created the base for guerrilla warfare in the country.

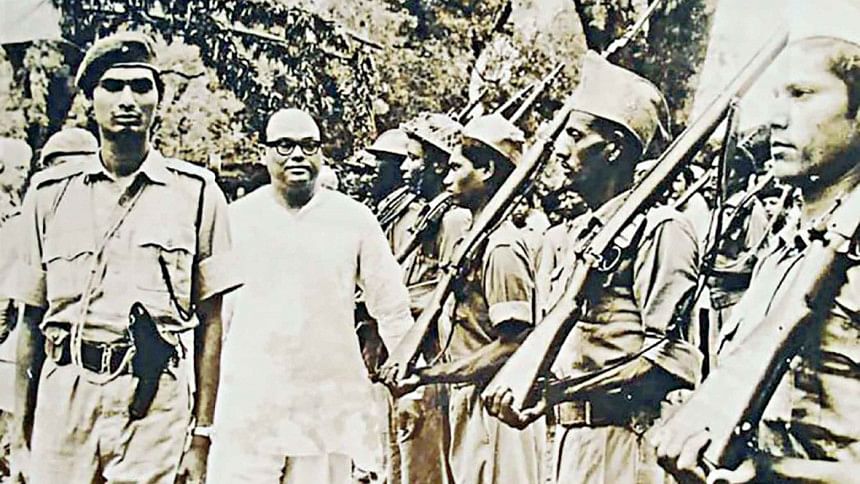

I had encouraged the local Sangram committees to get ready for arms training. I had instructed the Ansar and Mujahid Battalions of Jhenaidah to impart training to young students and juveniles. I opened up my Jhenaidah police station ground for training any person willing to take it. KC College in the locality was the training ground for another large contingent. We started training as early as March 18, 1971 and used dummy rifles and bamboo sticks. Our fight started just before the clock struck 23 hours on March 25, 1971. By that hour on that fateful night, the Pakistani 27 Baluch S and T Regiment was already on its way to Kushtia. Unfortunately for them, the route they chose to enter Kushtia was via my area, Jhenaidah. It became a fateful event in Pakistan's history of the war but, for us, the most incredible. Jhenaidah was the venue of my insurrection against Pakistan, where the enemy lost their initial attempt to destroy the Mukti Bahini, and all of them got killed. Within a couple of days of their passing over my territory, I had converted Jhenaidah into a fortress, creating trenches, cooking up traps, piling resources to mobilise in strength, and entrenching soldiers in the Mukti Bahini imbued with only one spirit, to fight the marauders. Such collective spirit of mind and heart, such enthusiasm and valour of ordinary folks, have never been observed anywhere else in the world. In the meantime, I had grown into prominence when I had the opportunity to award the Guard of Honour to the first Acting President of the People's Republic of Bangladesh at Baidyanathtala, now called Mujibnagar. This honour heightened my glory to the apex among the Mukti Bahini. This was who I was when, on a summer morning, I fell fast asleep in Gojadanga with my large contingent of responsibility.

We had established a listening post on a high tree at a distance of nearly 800 yards looking eastward to observe enemy movement in the vicinity. One of my original Mukti Bahini members, Kamaluzzaman from Jhenaidah, was on the post when the first light was thrown up. He abandoned his post, as was instructed to avoid peril. He came back running and said, "There is heavy enemy movement."

Nearly 40 members of the Jhenaidah Mukti Bahini accompanied me as a solid block of fighters. Others joined from places in Satkhira, Khulna and even Faridpur. Gun trotting Mukti Bahini members from Madhukhali and Madaripur joined with their own bands. A large contingent of EPR had joined me from Jhenaidah and continued at my beck and call under the leadership of Subedar Major Khairul Bashar, Subedar Jabbar, Lance Naik, later promoted to Naib Subedar Jahangir, and Sepoy Dudu Mia. The total strength was well into a few hundreds, a formidable fighting band to discern the advancing troops of 25 Baluch Regiment pitted against Salahuddin and me. With overwhelming firepower, alongside long and short-range artillery and guns, the early dawn attack was put into action. A part of 55 FF joined in with the Baluch to win a heyday. However, a wetland with swamp and quagmire was waiting for them in the jute and paddy fields of Satkhira.

By the time the Pakistani early dawn attack had infested the sky with untamed lights agog with sound and fury, they had lost two valuable hours. It was already dawn. We were dug in a higher ground along a two-kilometre-high bund. Now the counter forces were in full view of each other in the clear morning light. With a stretch of canal meandering behind us as the no man's land connected to India by a small culvert for offline rear movement, we were in no hurry to react. More so when the command was to be frugal with bullets, as we had a limited stock. It felt like a theatrical stage with attacks and counterattacks for the next two fatal hours to take one another down.

On May 29, 1971, the Pakistani Army drew up a well-orchestrated plan to uproot Mukti Bahini from its Bhomra position. 55 FF and 25 Baluch hatched the arrangement with the full-fledged support of Brigadier Durrani of the Jashore Brigade. The agenda was to wipe out the Bangalee Bhomra stronghold completely. However, they failed to realise their objective. At the end of 16 continuous hours of firing, cannon mongering and bomb blasting, they lost and had to leave in ignominy, with significant casualty and destruction. The loss was so complete that the entire regiment was disbanded and sent back to Pakistan.

The three thrusts of the Pakistan Army at the Battle of Bhomra are described below.

Bhomra Thrust One:

After two hours of tracer rounds crisscrossing the sky, the ground below was clearly visible, and the enemy could see the movement of the Mukti Bahini. They continued their errand in slow motion. We mobilised between flashes of the artificial lights and the darkness of the night. As a result, our real movement remained unknown. In these two hours of respite-less free shooting, they lost millions of bullets, and an unlimited number of mortar shells, bombs, crackers, long-distance and short distance.

We were within two kilometres of their target. I took my dependable companions, including police officers and EPR stalwarts and made a few rounds around the length of the trenches, where our boys were earnestly waiting to receive firing order against the enemy. The morning was bright, providing clear visibility. We were positioned at the right of our trenches, overlooking a pool of rice and paddy fields. The plants had thick stalks of rice and long stems of jute, which would allow the enemy to advance stealthily. However, I was sure the enemy did not know that they were walking onto an extensive swampy lowland.

Once they approached the vicinity of our firing range, with their heads down to avoid eye contact, all the trees and crops stood against their line of vision. Slowly but surely, they drew themselves into the wetland and got bogged down in perilous soft soil. Now they could neither go forward nor fall backwards. The most powerful, trained army of the time found itself slowed down with weapons thoroughly soaked in water. In this lull of enemy activity, our boys chanted "Joy Bangla" and started firing. A pathetic morning fell on the invaders who were now looking to retreat. But our boys' tirade continued to kill, maim or wound them in numbers they never thought possible. The firing continued unabated from our side for nearly an hour until all enemy movement fell into total silence.

After a few minutes of exuberance and celebrating our victories, we settled back into our positions; we also discussed and reviewed our following execution plans. I was walking back when I was left dumbfounded by a high-pitched explosion next to me. In less than a second, I found two men lying next to me in a pool of blood, limp and motionless. A split-second mistake in handling a grenade took away two of my Mukti Bahini members.

Bhomra Thrust Two:

After the terrifying defeat in their early dawn attack, there appeared to be little to no activity in the enemy ranks. I observed some movement along the road falling in my plain of vision. These enemy soldiers appeared to have been moving to achieve a specific target. They were using an expansive date garden with robust trees that was very strongly built. The garden allowed them nearly free movement. A level playing field was thus created between us on high ground. When their entire column fully entered the garden, they started shooting to keep our heads down. It was almost midday when Naib Subedar Jahangir came running from his trench to inform me that the enemy was leading a vigorous attack through the date garden. The only way to extricate them would be through the narrow canal right behind our dugout trenches.

Within our circumference, there were some abandoned mud houses. I realised that these structures could act as stone walls against any advancing high-power bullets or bombs, so I directed a few of my men and myself into these houses – this would become our protection.

I called for Dudu Mia, Sepoy of EPR, my dear mortar man, with a few rounds of 1.5-inch mortar. Dudu and I moved effectively within ten yards of our hind lines, commanded by Jahangir in the trenches under him. When we took up position behind a thick wall, counter firing was already razing like hell. It was an exchange of fire between modern automatics and outdated single shots and semi-automatics. I alerted the LMG men accompanying me and Dudu to prepare to fire. It was impossible to see the other side due to the obstruction of the heavyset trees. However, in a few minutes, all the noise from the enemy side ceased. They were completely diminished. Everyone standing in the mud hut areas and the trenches started screaming, "Joy Bangla!"

Bhomra Thrust Three:

The third thrust occurred at the central road leading from the Pakistani advance post to Bhomra high bund. Long-range artillery and guns continued defiling the sky and land in no uncertain terms to inform the enemy's intention to continue. However, the number of shelling was few and far between.

We regrouped, took some downtime and returned to our positions – some of us in trenches, others behind our lines under the sky's protection. I discussed the possibility of taking ammo from 13 Dogra Battalion to increase our firepower, so we could hold back the advancing enemy when the time came. I rushed straight into the field office of Colonel Nair. He ordered twenty thousand small arms bullets, a few thousand machine gun (MG) rounds and a considerable lot of high explosive (HE) grenades.

Amid the intermittent drop of bombs and artillery blasts, our head was held low to keep a safe composure. Finally, their movement was visible along the road to Bhomra towards our direction. This time they were mobilised in a one by one continuous fashion, zigzagging along the two sides of the road.

During this third and final thrust from our enemy along the Bhomra rib, they made a ferocious attempt to take over our position at the tip of the Satkhira Bhomra road leading up to the bund. I pulled up Dudu with a grenade thrower. I then took position at the back of the culvert, behind a mud wall, hardly 20 feet away from my forward trench, on the divide along the border. I asked Dudu to throw hand grenades. These grenades burst on the advancing enemy's front line, and they were forced to put their heads down. At that exact moment, all my boys in the trench who had grenades started throwing them on the enemy ranks who were trying to crawl ahead. The few grenades had a singular effect on the enemy again, and they stopped any further forward moves. This emboldened my trench men, and they continued shooting ahead while Dudu and I ran back to take our post in the trench.

As the enemy reached the vicinity of our range, the commander ordered targeted fire. Upon closer inspection, the number of Pakistani soldiers appeared dwindled, and their movement's pace seemed to have slowed down. It took another half an hour for us to maul the enemy heavily while they were trying to move towards our position at Bhomra. Approaching nearer, they stopped their backyard long-range support to avoid self-infliction and continued their tirade with powerful automatic weaponry. We replied with greater intensity. This continued for another thirty minutes when the enemy approach was very near. They were almost on us. It was time for a fistfight to stop them. In a few minutes, the big guys ran away into the woods or far behind, as far as they could, leaving behind the dead and wounded. They regrouped and continued firing on our boys from a reasonable distance, but they were still exposed in the open, making it easy for us to spot them.

Reporters came from as far as Kolkata to cover the news of the Mukti Bahini victory at Gojadanga, Bhomra sector of Sathkira. The Mukti Bahini ruled over the modernised army of Pakistan, a remarkable feat indeed.

We had suffered four casualties: Subedar Jabbar, Subedar Shamsul Huq, Abul Kashem, a member of Mujahid Bahini and Sepoy Abdul Mannan. Abdul Mannan and Kashem died in a trench waiting beside me when a grenade blasted due to improper handling of the pin. Subedar Shamsul Huq was killed in action on May 29, 1971, when the third wave of attack ensued. His memorial plaque stands high in a pool of bright light in front of the DC Satkhira office, honouring his high standard of training, discipline and bravery.

Mahbub Uddin Ahmed Bir Bikram was the Sub-divisional Police Officer (SDPO) of Jhenaidah during the Liberation War. He was in charge of presenting the guard of honour to the Acting President of the expatriate government of Bangladesh, Syed Nazrul Islam, at the oath taking ceremony on 17 April, 1971.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments