The Bastion of the Lalbagh Fort

This essay is largely about the pictorial depiction of the once imposing south-western bastion of the Lalbagh Fort in Old Dhaka, along with a brief history of the fort. When the Buriganga River flowed past the fort even in the late 19th century, its high rampart, parapet and the main bastion had offered an awesome picturesque view from the river. Consequently, the formidable bastion of the fort was the most visually recorded (sketched or painted) subject by European artists visiting Dhaka in the colonial era, before the river finally shifted its course. With the advent of the camera and the river having changed its course, the ruinous massive southern gateway became the most photographed remains of the fort. Today, the main bastion exists in silent dignity in reduced circumstances. It is sadly hidden from view, compounded further by the vagaries of nature and the foolhardiness of man. Unlike other Mughal forts or the hill-fortresses of Rajasthan in our subcontinent, the Lalbagh Fort, let alone its main bastion, can no longer be viewed properly from the outside due to reckless encroachment of buildings all around it, especially on the Kazi Reazuddin street. Today, regrettably, visitors to the fort are compelled to view it from within its premises, that is, see it from inside-out.

The Lalbagh Fort is the most important Mughal monument in Bangladesh. It was initially designed as a riverine fortress-palace, the construction of which was initiated in 1678, during the viceroyalty of Bengal under Prince Azam Shah, the third son of the last great Mughal emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir, at his behest. Azam aptly named the under-construction fort in honour of his father as Qila Aurangabad. However, Azam was recalled by the emperor in 1680. The construction of the fort was then taken up with renewed vigour by the next provincial Mughal Subhadar or governor Nawab Shaista Khan during the second term of his viceroyalty (1680-1688) in Bengal. But as ill luck would have it, the construction of the fort was abruptly halted by Shaista Khan at the sudden death of his favourite daughter, Iran Dukth alias Pari Bibi, who was alleged to have been betrothed to Prince Azam. A bereaved Shaista Khan thus left the construction of the fort incomplete considering it as inauspicious. Had it been completed as per its original plan as envisaged, it would have been a gem of a small Mughal fortress-palace on a miniature scale, when compared to other important, sprawling Mughal fortress-palaces at Delhi, Agra, Fatehpur Sikri, Allahabad or Lahore.

From the remnants of the unique design of the impressive, yet incomplete three-storeyed southern main gateway of the Lalbagh Fort, it is amply clear that it was not designed as a siege-fort, but more so as a pleasurably fortified residential accommodation with a Charbagh or quadrilateral garden, especially to entice the recalcitrant imperial Mughal princes who were too often reluctant to proceed to Dhaka as Subhadars (provincial governors) because it was considered as a hardship posting. They dreaded coming to deltaic, tropical Bengal (read Dhaka) deemed as an unhealthy place, circumvented by mighty rivers (which awed and frightened them), negotiate its innumerable network of canals, formidable jungles with ferocious wild beasts and venomous snakes, huge swathes of malarial swamps, and bear with prolonged torrential monsoonal downpours and annual flooding. On top of all that there was frequent illness from pestilence due to the damp weather. Death was quite rampant from a myriad of causes. Although, the princes and nobles would endure the infernal summer heat of upper India they, nonetheless, preferred the dry climatic conditions there which ensured better heath. At that time Dhaka also did not have any befitting residential accommodation and most Mughal viceroys had to live in tent encampments in winter and wooden houses in the summer months. The old Afghan fort which was later incorporated into the 19th century Dhaka Central Jail was small and unattractive for residential purposes and holding of court by the Mughal viceroys. Therefore, at the slightest opportunity the Mughal princes as Subhadars (governors) in Dhaka were inclined to relocate their capital to Rajmahal in neighbouring Jharkhand with its drier climate, scrubland and undulating hilly terrain. That is why emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir had ordered his successive governors both Prince Azam and later Nawab Shaista Khan to build the new fortress-palace at Lalbagh as a permanent accommodation for Mughal viceroys, particularly the imperial princes as a befitting abode in the provincial capital city of Jahangirnagar (Dhaka).

A general comment on the salient features of the images:

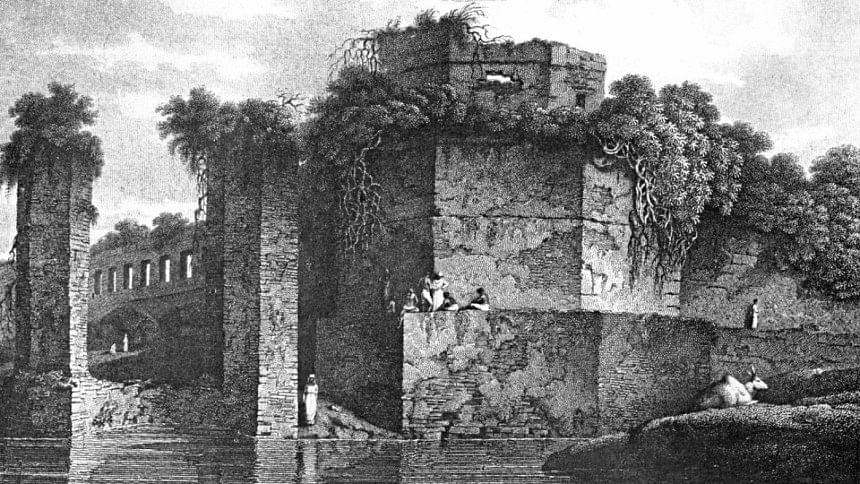

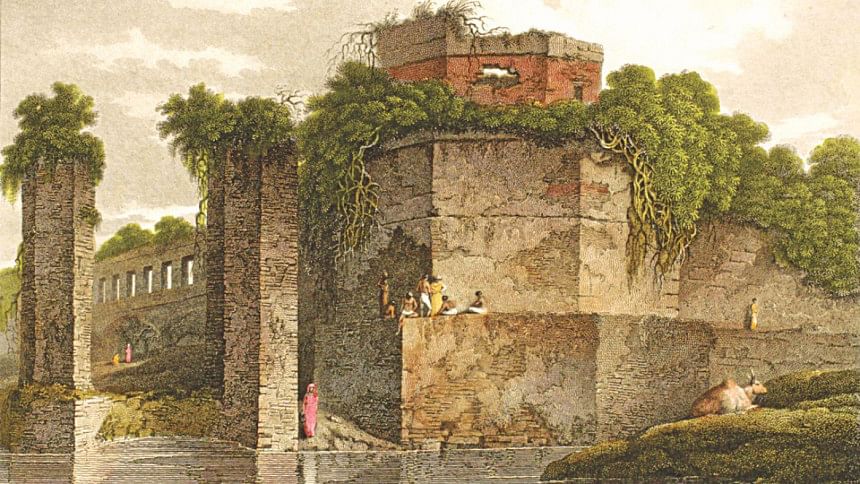

The first (uncoloured version) and second (coloured version) images pictured above are basically the same drawings of the Bastion of the Lalbagh Fort by Sir Charles D'Oyly. While the uncoloured version was published with other folios in the book Antiquities of Dacca, from London in 1816, when Sir Charles was still the Collector of Dhaka, the coloured version of the same book was published later in 1823. In 2017, I met with Sir Hadley Gregory D'Oyly, the 15th Baronet in Dhaka, a descendant of Sir Charles D'Oyly, the 7th Baronet (the artist). He confirmed the veracity of a coloured version of the Antiquities of Dacca, but could not give a precise date of its publication year. However, I now have it confirmed from the eminent British Art Historian, Charles Greig, that there is indeed a coloured version which was first published from London in 1823. Observe the growth of invasive wild vegetation at various points of the ruinous fortification in these images.

Clearly visible in these images, even at its unfinished stage, is the huge bastion or enormous outcropping which once formed the base of the highest point of the fort with a multi-purpose octagonal Burj or watch tower crowning its top. The Burj was raised as a secondary structure based entirely inside or upon the primary structure, that is, atop the bastion. Apart from being a vantage point for observation and cannonade to ward off any approaching danger from the river, it could also have alternated as a hawa-khana (airy-pavilion) to catch the pleasant evening breeze for the Subahdar and his harem/zenana ( comprising of noble ladies, concubines or nautch/dancing girls).

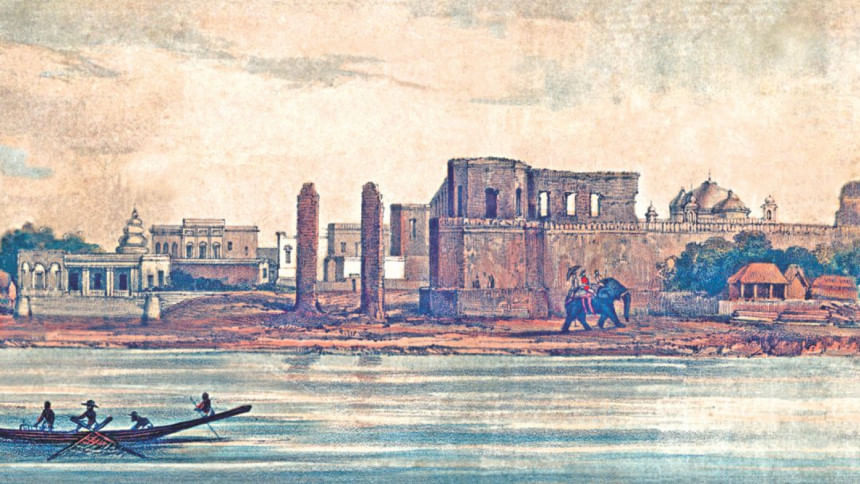

The third image is a very rare painting, hitherto unseen in the public domain, of the bastion of the Lalbagh Fort painted by the famous British artist, Robert Home, on his visit to Dhaka in 1799. The initial drawings was probably executed from a boat or barge moored at a vantage point in mid stream of the Buriganga River and, later on painted in oils. It is quite possible that the artist employed the Camera Obscura technique to make the initial sketch. The painting show the river either at high tide or during the monsoon floods. This painting also shows the growth of invasive wild vegetation at various points of the fort.

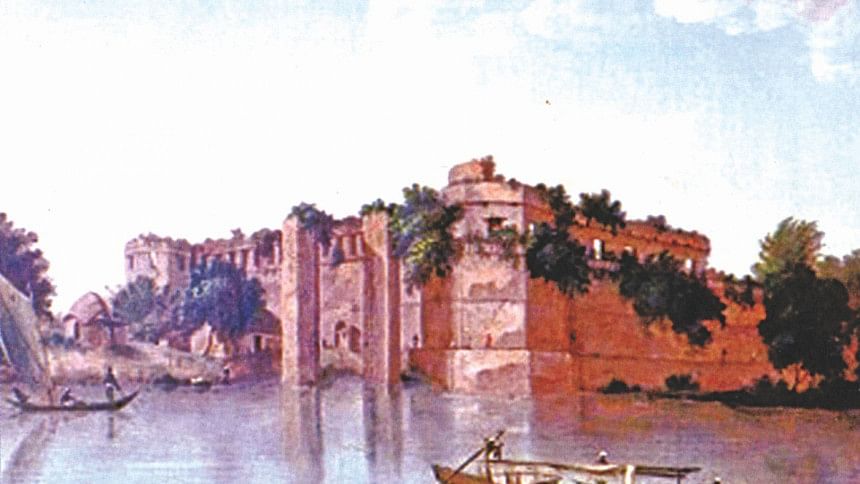

The eye-catching picturesque fourth image of the south western bastion is a single folio from a 4-foot long foldout scroll of the "Panaroma of the City of Dacca", by an unknown artist dated 1847. According to Charles Greig, the Dhaka panoramic scroll is now regarded as the finest and most exquisitely painted miniature scroll amongst all such picturesquely painted panoramic scrolls done of other major cities in colonial India. Thus, we can take genuine pride in such a revelation. In the Dhaka scroll, the artist also seems to have made the initial drawings from a boat or barge moored in mid-stream of the river. Here again, the artist probably resorted to using the Camera Obscura technique to do the initial drawings. Note that the ruins here appear to have been cleared of wild vegetation growth. It is also interesting to observe an East India Company official in a red coat and white breeches, sitting atop a lumbering elephant while going past the fort across the river with his khidmatgar (valet) holding a parasol over his head to shelter him from the sun.

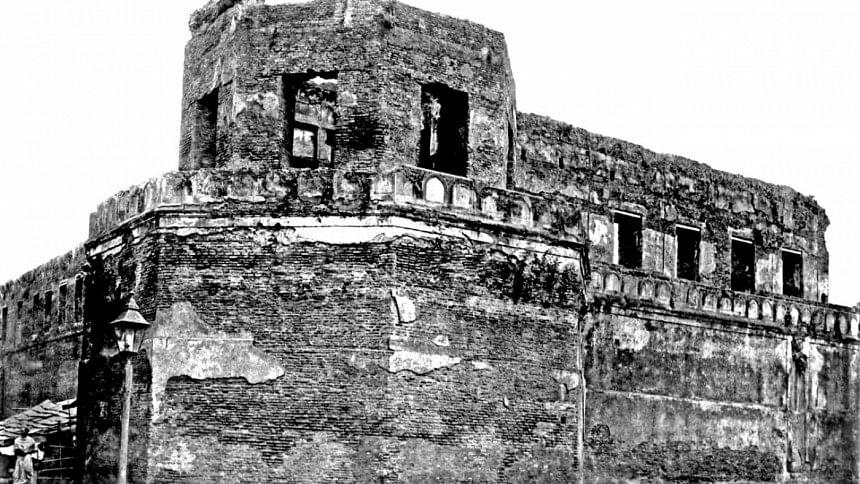

The fifth image, a rare photograph taken in 1950, soon after the partition of British India in 1947, shows the south western bastion of the Lalbagh Fort already much reduced in height on Kazi Reazuddin street, which was created when the river changed its course. It is interesting to note a kerosene street lamp of the colonial days still in use then. A Batti-wallah (light-man) with a portable bamboo ladder employed by the Dhaka municipality was entrusted to ritually alight the wick of these street lamps after dusk and put it out at dawn. Observe that the ruins here are almost free of weed or invasive wild vegetation unlike in the painted images.

Epilogue: In images one to four rather curiously lofty, oblong twin pillars slightly set apart can be seen to the immediate left of the south-western bastion of the fort on the edge of the river. These peculiar structures which apparently look like a gate for a landing ghat or quay for river vessels are not evident in any other Mughal fortress-palace in the subcontinent. These are unique structures. In hindsight, having deliberated upon it for long, I am now convinced of the utilitarian purpose of these two high pillars. The functional use of these two columns was to facilitate the circulation or rotation of a large Persian wheel (a Ferris wheel look-alike) suspended between them, to supply water directly from the river via pails attached to the Persian wheel which poured water through a channel into a reservoir. A network of clay pipes then fed water from the reservoir into a larger aqueduct within the palace premises for storage. Such a large Persian wheel with buckets for collecting river water was operated either manually or with the help of bullocks. Behind the mausoleum of Pari Bibi and the mosque within the fort are curious remains of large brick and mortar underground storage water-tanks set at ground level. Surprisingly, to-date, this fact has never been mentioned in any history book or journal while discussing the Lalbagh Fort. In 2004, when I broached this subject with the distinguished archaeologist Dr Nazimuddin Ahmed, the first Director of the Archaeology Department of Bangladesh, he fully endorsed my point of view. Most recently, I had a detailed discussion on this subject with Architect Professor Dr Abu Sayeed M Ahmed, a notable and experienced architectural/heritage conservation specialist in the country, who is knowledgeable in such matters. He not only agreed with me, but has already started to discuss and teach his university students regarding the water supply system of the medieval Lalbagh Fort, using relevant diagram of a Persian wheel. Thus, the riddle of these two oblong columns which had bedevilled me for long has finally been resolved.

Waqar A Khan is the Founder of the Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies.

Comments