The current status of Jerusalem

This is an excerpt of the paper delivered by Edward Said, author of the famous book Orientalism, at a conference on Jerusalem held in London on 15-16 June, 1995. It is nevertheless striking how accurate its description of the reality in Jerusalem remains, in spite of all that has changed since then.

I want to draw attention to the quite extraordinary act of historical and political neglect, whose effect had been to deprive us of Jerusalem well before the fact. … If we want to come to a full understanding not only of Israel's designs and accomplishments in the Eastern city since 1967 but also of what Palestinian designs and accomplishments have amounted to, we must be prepared to admit that an astonishing disparity exists between the two sides in the contest over Jerusalem. This was certainly true in 1948. It is, I am very sorry to say, equally true in 1995, although now we Palestinians claim that we have a legitimate representative who since the summer of 1993 has been engaged in direct negotiations with Israel over the transitional period; these talks are to lead to final status negotiations.

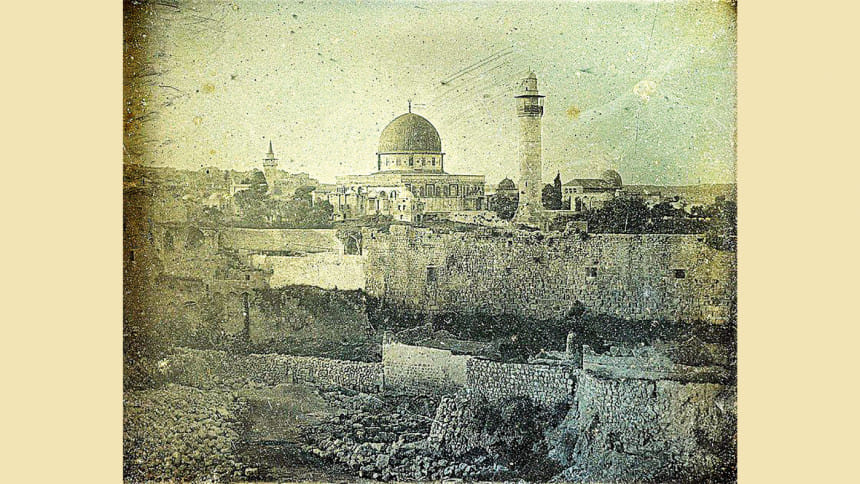

I believe it does need to be said, and reiterated that an Arab Palestinian claim in Jerusalem – a very real claim based on history and culture – does exist and must very strenuously be made. But it cannot, in my opinion, be made with any credibility at all unless the history of our gradual loss of Jerusalem is understood precisely and dispassionately to begin with. Only then can we begin to understand what is necessary for the claim to be pressed with some modest hope of success. Consider that at the time East Jerusalem was occupied by Israel in early June 1967 there were approximately 70,000 Palestinians who lived there and in the nearby villages. Almost 200,000 Jews lived in West Jerusalem. By the end of the month the barrier between East and West was eliminated, and the city's municipal boundaries were set at twenty-eight square miles, an area that included the Eastern part of the city. Kollek took over the city council, which so far as its Arab component was concerned was summarily dissolved, and over the years the two halves of the city were welded together. Although the Palestinian population doubled to about 150,000 in the early nineties, they were allowed to build on about ten to fifteen percent of the land. Israeli Jews in East Jerusalem now [1996] number about 160,000. Nearly ninety percent of new building was for Jews, about twelve percent only for Arabs. Expropriations of land in and around Jerusalem have been systematic; its area has been increased; and the city is now surrounded by a ring of massive (and massively ugly) Jewish settlements that dominate the landscape, stating the provocative idea that Jerusalem is, must be, will always be a Jewish city, despite the existence of a sizeable, albeit disabled and encircled Palestinian population. …

Thus Jerusalem in its current expanded form accounts for about twenty-five percent of the West Bank. Its Palestinian residents have an anomalous and resolutely eccentric status given them by Israel. Although Israel has annexed East Jerusalem, its non-Jewish residents are not citizens, cannot vote except in municipal elections, and have the legal designation of "resident aliens." During the Israeli-joint Palestinian-Jordanian negotiations that began after the Madrid Conference in Washington (late 1991) residents of Jerusalem were not permitted by Israel to be members of the negotiating team, and now, even during the discussions concerning elections that have been taking place between Israel and the Palestine Authority, the question of whether Palestinian residents of Jerusalem may or may not vote is a thorny one. On the other hand the closure of Jerusalem to most of the inhabitants of Gaza and the rest of the West Bank has created great hardship for them since, as Israel well knows, East Jerusalem is the hub of the West Bank; any design terminally to fortify, isolate and incorporate it into the scheme of "separation" now being pursued by the Labor government in effect means amputating it from its natural connections with the rest of the Palestinian territories, as well as gouging out a gaping hole in the territories which would permanently impair them.

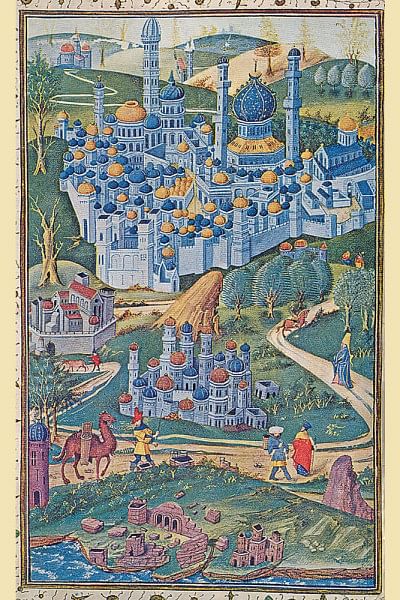

But this is exactly Israel's plan which, in effect, is an assault not only on geography but also on culture and history, and of course religion. Whatever else it may be, historical Palestine is a seamless amalgam of cultures and religions, engaged like members of the same family, on the same plot of land in which all has become entwined with all. Yet so powerful and, in my opinion, so socially rejectionist is the Zionist vision that it has seized on the land, the past, and the living actuality of interrelated cultures and traditions in order to sever, carve out, unilaterally possess a territory and a place that it asserts is uniquely its own. Here again Jerusalem is an excellent example of what I mean. It has had a recorded history of some 10,000 years, during which an almost unimaginable series of conquerors, inhabitants and coexisting traditions have maintained their presence sometimes harmoniously, sometimes precariously. It would be extremely difficult now to say – using any mathematical or equitable formula at all – that the predominating influence in the city over the whole period was Jewish. Certainly for the last 3,000 years there has been a Jewish presence and, for a short period before and shortly after the beginning of the Christian era, there was a Jewish kingdom with its capital in Jerusalem.

But there has been a longer, more continuous Muslim presence, and certainly a very dense Christian one too. To override all this by saying that only the Jews have a right to exclusive sovereignty over the city is, I believe, a very willful and insensitive act which has the effect of dispossessing everyone else. I will not deny at all what many scholars and religious experts have said, that Jerusalem occupies a special place in the Jewish religion and tradition, perhaps even more special than that of any other single group. But admitting that does not by any means guarantee Israel's right – Israel after all is a modern state – to say that Jerusalem is its eternal undivided capital to the exclusion not only of the city's present Palestinian population, but also to its past, extremely varied, mottled, and interesting in multi-cultural terms.

I find the whole debate about the possession and concrete ownership of Jerusalem in these terms to be extremely unpleasant, unedifying and objectionable. It neither does justice to the nobility of the city's unparalleled aura and grandeur, nor to its unequivocally rich-textured history of religious, cultural, and even political significance. The saintly Bernard of Clairvaux, preaching in the heart of the Burgundian countryside had no compunction at all in proclaiming the centrality of Palestine and the necessity of crusading several thousand miles in order to possess it. Seventh-century Islam, although much closer to Palestine than Europeans were, did something of the same thing without, however, that appalling disregard for and demonization of the Other that is very often the European hallmark. And in a perspicacious study of the role of territory in the Jewish imagination, Uri Eizenzweig has described the projections, fears and exultancies that characterize the role of sacred land for Jews in Europe.

But of course it is one thing in a scholarly way to examine the pattern of the past, and quite another to confront the coarse interjections of the present, those, that is, by which Israel since 1967 has adopted in Jerusalem. The plan is nothing less than to dispossess Palestinians and turn them into a numerical minority, at the same time building up, interposing, implanting a fortified Jewish presence that will either dwarf or totally marginalize all the other of the city's myriad actualities. …

In the main, however, Israel seems undeterred, aided and abetted in the stampede by members of the US Congress who have started a drive to move the US Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, thereby breaking with a constant in US foreign policy since 1948.

The most impressive thing about all this is not just that with the US employing its Security Council veto to protect Israel's delinquent, not to say criminal, behavior, the international community seems powerless to say or do anything, but that the Arabs and Muslims together, plus especially the Palestinians have yet to mobilize their considerable resources to counteract Israel's behavior in Jerusalem. Why for example was the Arab League summit, which had been scheduled as a response to Israel's announced expropriations, summarily canceled? And why, despite endless amounts of evidence proving Israel's bad faith, does the Palestine Authority supinely proceed with its negotiations, all the while doing absolutely nothing either locally or internationally to mobilize Palestinians against Israel's continued assault on Jerusalem?

To get answers to these questions we must first ask why in the Declaration of Principles itself Jerusalem, already annexed illegally, already aggressed against in all sorts of ways, was split off from the West Bank and Gaza and left, or rather conceded, to Israel from the outset of negotiations? The answer must lie in two closely connected facts, (a) that being much more powerful and backed to the hilt by the US, Israel simply asserted that fact unilaterally, reserving for itself the right to do what it wished both in Jerusalem and elsewhere and (b) the Palestinian conviction that there was no other alternative but to make that, as well as many other concessions. The implications of all this have been well spelled-out in a scrupulously careful study of the Oslo Accords by Burhan Dajani, which appeared in the Journal of Palestine Studies. One passage, which underscores not so much only the weakness but the prior moral capitulation of the Palestinian leadership, deserves quotation:

Given the power configuration, the only way the Palestinians can secure any gains in the welter of negotiations unfolding is in exchange for concessions. (For Israel, of course, anything it offers as a concession or sacrifice would be seen as requiring compensation by the United States and regional bodies and through regional funds.) The question is what the Palestinians have left to concede. They can make concessions on the delimitation of the territory of the self-governing authority [and have already done so in Cairo on May 4, 1995], concessions to the jurisdictions of the various authorities [each of which is carefully sculpted for them by the Israelis, then handed to them on the understanding that nothing the Palestinians do should go against Israeli interests or security; if they do then Israel can re-intervene], and – inevitably – concessions on the status of Jerusalem and the final shape of the so-called permanent status. Indeed, this "permanent status" will be no more than what is left over at the end of the transitional period; everything that is chopped off and conceded during the transitional period will be taken from the permanent status.

There is a valuable insight into the mentality that produced so catastrophically supine an attitude near the end of Hanan Ashrawi's recent book This Side of Peace. Expressing some dismay at the text of the Declaration of Principles Ashrawi is told by, as I recall, the architect of the accords, Abu Mazen, that she should not worry. We shall sign now, and then, he says chivalrously, you can bargain with them to try to get back the things we have conceded. I wonder where this prodigiously endowed intelligence got its ideas, or its impressions – they were scarcely more than that – about how the Israelis work, how they sign agreements, how they concede, and so forth. Dajani does well to remind us that it took the sovereign country of Egypt five years to win back the less than half a square mile area of Taba, and this with a mobilized foreign office, enormous experience and training in diplomacy, and little interest in Taba by Israel. It is also perhaps worth recalling that the Palestine Authority usually negotiates without consulting lawyers, with no experience whatsoever in settling international disputes, and with no real conviction in actually winning anything at all, except what Israel might deign to throw its way. The problem of Jerusalem in the peace process today is therefore largely a problem of the incompetence, the insouciance, the unacceptable negligence of the Palestinian leadership which has in the first instance actually agreed to let Israel do what it wishes in Jerusalem, and in the second instance evinces not the slightest sign that it is capable of comprehending, much less executing the truly herculean task that is required before the battle for Jerusalem can really be joined.

If then Jerusalem has been taken from the Palestinians by Israel, dispossessing them of it, what are some of the steps that need to be taken, what are the values and principles that need to be asserted, what are ways by which it can be re-possessed in the future? Jerusalem, for all its vaunted sanctity and importance, is no different from the other Occupied Territories in principle: that is, according to international law, it is not Israel's alone to dispose of, or to build in, or to exploit to the exclusion of Palestinians and others. From the outset then we need a clear statement of purpose and principle to guide our way, and if this in effect involves re-thinking and re-doing Oslo, then so be it. Israel has been re-interpreting, or rather violating Oslo, all along. The principle is this: there is a massive Palestinian-Muslim-Christian-multi-cultural reality in Jerusalem, and we will not tolerate either its obliteration or its supervention by Israel. Our role as Palestinians, as parties to and believers in a just peace between Israel and the Palestinian people, is to insert that fact into the peace process, from which over the past several years it has gradually been forced out. But it will do no good merely to say this –– unless the saying is part of a general strategy both of negotiating and in fact winning the peace that we desire.

Simply to speak about East Jerusalem mechanically as Arab is not enough. I myself do not at all believe it is in our interests as a people to introduce another division in a city that has remained ethnically separated albeit municipally glued together in the manner that Israel has done it; I think it would be much better to set an example, and provide an alternative to such methods as Israel's by projecting an image of the whole of Jerusalem that is truer to its complex mixture of religions, histories and cultures, than the one of Jerusalem as something that we would like to slice back into two parts.

Of course East Jerusalem is part of the occupied West Bank, and this point needs to be made over and over again; as such therefore it has to be re-connected with the whole issue of liberating Palestinians from the burdens of being under Israeli occupation. But beyond that Jerusalem is the one place, which, for the reasons I gave earlier, really can be a site of co-existence and sharing between us and the Israelis, and so we should insist on that, i.e. speak of Jerusalem as a city with joint sovereignty, joint and cooperative vision, which we do based on the principle of our self-determination and independence as a people and as a society.

The realities are of course much less simple and ennobling than that. Israel and the United States between them now in effect control the peace process and for twenty-eight years Israel has been adding to, plus implanting new, settlements. Jerusalem is part of the same policy, except that the pernicious slogan – Judaizing Jerusalem – has been openly put to service in the city as well as internationally. This has to be dealt with frontally, in my opinion, both by a coordinated, well-planned information campaign stating the facts, bringing it to the attention of Jerusalem's enormous worldwide constituency, as well as by a firm policy of re-connecting Israeli land-grabs, illegal building, and the like with the ongoing peace negotiations. A huge amount of time has been wasted. Israel began trying to change the character of Jerusalem from the moment it entered the city: its shameful record must be placed before the Arab, Muslim and Christian worlds who after all do have a stake in this business. Above all, we need to disprove the fraudulent claim that Jerusalem is, and always was, an essentially Jewish city. This simply flies in the face of the facts but, as no one needs to be reminded, the facts do not ever speak for themselves. They must be articulated, they must be disseminated, they must be reiterated and re-circulated….

Unless Jerusalem is re-projected and represented as a jointly held capital, not as an exclusively Jewish capital, it will continue to be hostage to Israel's deeply offensive designs. …

There is a generously eclectic history of Jerusalem to be excavated and inserted into the debate now dominated by Israel; there is also a redoubtable set of other, non-Jewish interests to be made clear; and there is at very least, a truer map to be drawn and clarified and mobilized around. Tacit acceptance or silence in the face of uncontested assertions must be dispelled, and dissolved. This means explicitly advancing a much clearer, more principled Palestinian view of peace and, at the same time, rigorously criticizing the origins as well as the course of Palestinian participation in the negotiations.

For perhaps the time at last approaches when the Arab world can begin to free itself from the miserable, impoverishing and undemocratic life imposed on it by its leaders. A campaign for Jerusalem of the sort I have been speaking about is part of that process, and it is certainly a strong antidote to the drifting, impossibly unwise course now being undertaken by the Arabs, Israelis, and Americans beneath the tattered banners of the peace process. …

Perhaps Jerusalem, with its thousands of new Jewish residents, its dislodged Arabs, and its illegally acquired spaces is already lost. If it is, then peace in this generation is not at hand. This needs to be clearly understood and acted on with intelligent determination. On the other hand, it is never too late for a vitalized and energized political will to spring into action, and then maybe, just maybe, a better peace can occur, although it may be not for us here ever to see it with our own eyes.

Edward Said was a professor of literature at Columbia University, a public intellectual, and a founder of the academic field of postcolonial studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments