The Enduring Enigma of Columbo Sahib!

It stands proudly as a silent sentinel - forsaken, forlorn, dilapidated - entwined in the vicious vice-grip of invasive vegetation – serpentine vines and clinging creepers - that threaten to bring it down anytime sooner than later. Yet, it audaciously mocks the vicissitudes of time and the vagaries of nature, by maintaining its lonely vigil over the 300 year old Christian cemetery at Narinda, Wari, old Dhaka. More than a hundred years ago, Francis Bradley Bradley-Birt (1874-1963), ICS, a British civil servant and writer in his book on Dhaka, a slim volume entitled: 'The Romance of an Eastern Capital', 1906, had also made a similar observation. He said eloquently," It stands namelessly, dominating the whole cemetery and jealously keeping watch over the three graves that lie within." It is the unique mausoleum of an enigmatic Columbo Sahib, I am referring to here. It is perhaps the best kept secret of Dhaka's past history. So, who was this mysterious Columbo or Colombo Sahib, whose remains purportedly lie buried within this imposing funerary monument? Let's proceed.

It was in 1970, when I first visited the old historic Christian cemetery at Narinda, on a cold and dreary winter afternoon. I spent a good deal of the time surveying the interesting graves, tombs and mausolea trying to read the epitaphs. The place looked wild, desolate and uncared for. The mausoleum of Columbo Sahib was the main attraction. Fifty years ago, although in a state of abject neglect, it was in a better state of preservation. The eye-catching old edifice intrigued me. Meanwhile, by 4:30 pm dusk had started to descend and jackals howled. There was not a soul in sight. It felt eerie. A sudden ominous foreboding gripped me, and I shuddered. As I hurriedly left the cemetery, a gentle breeze rustled the dry leaves and in my fervid imagination, I thought I heard strange whispers in the wind. I quickened my pace hailed a rickshaw and fled. And, that was that, until a revisit in 1973, and subsequent visits thereafter.

The name Columbo Sahib first appears, the metropolitan Bishop of Calcutta, entitled, 'Narrative of a journey through the Upper Provinces of India, from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824-5, with an account of a journey to Madras and the Southern Provinces,' published after his death by his wife Amelia Heber from London in 1828. An intrepid traveler Heber during his Episcopal tour visited Dhaka in 1824, and consecrated the Narinda cemetery. He was naturally drawn to the impressive unidentified tomb there, and inquired of the chowkidar as to who it belonged to. In reply the guard said something to this effect in Hindustani, " Yea Kalumbo Sahib ka maqbara, Kampany ka naukar,"(It's the tomb of Columbo Sahib, a servant/employee of the East India Company). The Bishop zealously took it down. However, it is to be noted that Bishop Heber a very resourceful person, also failed to identify this wealthy Christian personage. And, that is how the mausoleum got its name as the tomb of one Columbo or Colombo Sahib from a chowkidar! But the question endures to this very day: who was this Columbo Sahib? Surprisingly, he is completely missing from the pages of Dhaka's past history! To date, there is absolutely no mention of him or his identity anywhere in the old Persian, Urdu, Bengali or English chronicles available here.

Let's take a quick tour of a major portion of the Narinda cemetery. In the vicinity of Columbo's tomb are some old graves worthy of mention. These are the double tombs of Robert Crawford, the factor of the East India Company and his wife dated 1776. The mausolea of Wonsi Quan of 1796, a Chinese convert to Christianity—which bears no inscription to identify the persons buried in it and that of Joseph Padget in 1724, a Padre from Calcutta. There are some other interesting old tombs elsewhere in the cemetery. Dr Nazimuddin Ahmed the renowned Bangladeshi archaeologist, described the salient architectural features of Columbo's tomb as follows ,"The edifice has a high octagonal tower with eight arched windows surmounted by a dome. Slender round pilasters, faceted at intervals, occupy each corner of the octagon in three stages and vary in elevation, whilst a single band of blind merlons run right across the shoulder of the building in two stages." The mausoleum is actually a three storied building with a clearly delineated amalgam of composite architectural styles. While the base structure resembles a Mughal mosque with four evenly spaced arched doorways, the next floor above exhibit gothic features, and the uppermost cupola is tinged with a baroque flavor. Viewed from within, the circular ceiling of the tomb with the eight arched open windows offer a spectacular sight, with flecks of the original paint still visible on the ceiling after centuries. However, generally judged from its exterior façade the tomb may appear to the casual observer as a curious Mughal/Islamic style edifice. In the height of the monsoon season camouflaged in luxuriant greenery, Columbo's tomb peeps through a canopy of verdant foliage like an 'ageless bride' offering a most romantic visage, which can evoke in one an irresistible urge of poetic impulses.

The etymology of the name Columbo, surprisingly show Italy as the place of its origin. The name means dove in Italian, which was once used for naming of orphan children there. Thus, contrary to popular impression that the name Columbo is of Portuguese or Spanish origin, this findings may seem to be a bit puzzling at first. It is also interesting to note that the highest concentration of people with the surname of Columbo, reside today in the western hemisphere, namely in the USA and Canada. However, this etymological version is contested because of the fact that the famous name Columbus, when translated into Portuguese is known and pronounced as Columbo. Therefore, it can be safely concluded that it is a Portuguese name.

Tim Steel, a British amateur archaeologist, history buff and writer who once lived in Dhaka strongly felt that Columbo Sahib, was a merchant who came to Dhaka from Colombo to trade and prospered hugely. Thereafter, he came to be famously known locally as Columbo Sahib after the city of Colombo. Although, speculative it is a plausible theory and cannot be ruled out completely. I am also inclined to think that Columbo could have been a Portuguese or even a Sri Lankan Sinhalese Christian who came to Dhaka from Colombo. He could also have been a local Luso-Portuguese gentleman from the Indian subcontinent. The Portuguese connection is also attested to by Charles Greig, a notable British art specialist, historian, connoisseur and antiquarian. He wrote, "I think it is also a very real possibility that Columbo was Portuguese - the translation of the name we know as Columbus is Columbo in Portuguese. At the time that the tomb was built (in my opinion) - circa 1670-80 - there was still a very strong presence of Portuguese traders in Dhaka. Moreover, the early Church at Narinda seems to have been Catholic."

However, Dr Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, MBE, the eminent British historian of the 'Nawabi Lucknow fame', posits that Columbo was probably sent by the Dutch East India Company from Colombo, Sri Lanka to Dhaka to look after the Dutch commercial interests. And that his tomb has a striking resemblance to the famous grandiose Mughal/Islamic style Dutch mausoleums in the old Dutch-Armenian-English cemeteries in Surat, India. She says, "my supposition that Colombo Sahib's tomb may mark the resting place of a Dutch man is based on comparisons with the Dutch tombs in Surat, together with information that Dutchmen were sent to Bengal, from Sri Lanka, (the capital Colombo in particular), to start textile trading from Dacca in the middle of the 17th century. We may never know, unless someone is prepared to go through the VOC records at the Hague." It is a fact, that there is no other place in the entire subcontinent not even in Calcutta except in Surat, where likeness to Columbo's tomb can be observed which lends an unique dimension to its importance as an exceptionally rare funerary monument worthy of immediate restoration and preservation for posterity. It is our national heritage!

A word about the unique Mughal/Islamic style Dutch tombs and mausoleums of Surat. In the 17th century in particular, when Surat was an important port city ( 'Bandar-e-Mubarak ' or the 'Blessed Port') under the Mughals, the European traders in Surat emulated the ostentatious lifestyles of the Mughal nobility and grandees there to make a statement. As wealthy European 'merchant-princes' (read Dutch in our case) they too wanted to earn the awe and respect of the local populace of Surat, by flaunting their opulent lifestyles by imitating the Mughals, both in life and in death. Nowhere else in the subcontinent, is this more evident than in the city of Surat, India, where grandiloquent tombs and mausoleums left behind by the Dutch, Armenians and even the English can be seen in the old cemeteries. The most impressive and extravagant Dutch tomb in Surat is the 17th century mausoleum of the Dutch governor, Baron Adrian Van Reede (1636-1691), the director of the Dutch East India Company. Most of these remarkable collection of 17th and early 18th century Dutch tombs and mausoleums in Surat, can be easily confused for those of the Mughals.

Also, debatable is the fact that Columbo died in Dhaka around 1728, according to the records of the 'British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia' (BACSA, UK). If this date of his expiry is taken to be true, then he died a good 37 years prior to the conquest of Bengal by the East India Company in 1765. Therefore, he could not have been an employee of the Company as recorded by Bishop Heber as per claim of the chowkidar in 1824. Charles Greig who closely inspected the mausoleum of Columbo on his visit to Narinda in 2012, pushes back Columbo's presence in Dhaka by several decades to circa 1670s-80s, during the reign of the last great Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir I. However, only a proper carbon dating of the original bricks of the monument and other relevant indicators can precisely determine the date of the tomb's completion, and thereby also help calculate the year of Columbo's death.

Now, let us briefly discuss the images in the numbered plates. Plate-01: This beautiful landscape painting showing Columbo Sahib's mausoleum was done in 1769, by arguably the most famous European artist ever to visit India, Zohann Zoffany. On this, please refer to my article online titled: 'The Dhaka Masterpiece Paintings'. The exquisitely detailed Narinda painting is undoubtedly an exceptionally rare and invaluable visual document of Dhaka's past history. It not only shows the earliest known image of the spectacular funerary monument of Columbo Sahib on the bank of the now extinct Dholai Khaal (famous Mughal era canal) on a gorgeous moonlit night, but also highlights a range of ongoing nocturnal activities at play. It shows images of wild looking Naga ascetics gathered for their Naga Panchami festival, while at the same time stoking the fire of their dead on a funeral pyre. The mesmerizing effect of the fire and the moonlight makes the entire landscape not only luminous, but one of spectral beauty. Next to Columbo Sahib's tomb can be seen an elegant rajbari (palatial mansion), which I strongly believe to have been the house of Columbo Sahib and his family. They could have been residents of Narinda originally an old pre-Mughal settlement. Furthermore, to the horizon gleaming in the moonlight, is the small historic single white-domed mosque of Binat Bibi (Bakht Binat) built in 1454. This again, is the earliest known image of the oldest mosque in Dhaka, which has now lost much of its original architectural features.

Plate-02:

This is one of the earliest known photographic image of Narinda cemetery showing its main gateway leading to Columbo Sahib's impressive mausoleum to the right. The photograph was taken by the renowned Calcutta based European Photographic studio named Johnston & Hoffmann in 1875. Dr Nazimuddin Ahmed opined that the gate was a latter addition to the cemetery and was, therefore not a contemporary edifice to the Columbo tomb. However, in plate-02 the tomb of Columbo curiously appear somewhat visually bigger in size when compared to its images in plate- 01 (painting) and on plate- 03 (photograph of 1950), where both the Columbo edifices look more elegant and slender in form. In fact, the bulkier looking Columbo tomb in plate- 02, is probably a photographic (visual) aberration. Nonetheless, it does correspond very well with the two photographs of the old grandiose Dutch tombs in Surat, shown in plates: 04 and 05, with strikingly similar architectural features.

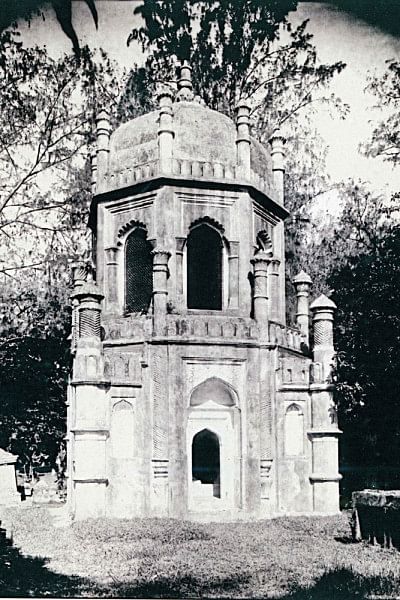

Plate-03:

It shows a radiant Columbo mausoleum in the morning sunlight taken in 1950. It was still in a pristine condition then. The remnants of Columbo's grave can be clearly seen through the main arched entrance to the tomb. Dr. Nazimuddin Ahmed who was present during taking of this photograph told me that he saw three unmarked graves within the mausoleum in reduced circumstances, but still clearly visible and demarcated. There was a larger grave in the middle (presumably of Columbo himself) flanked by two additional smaller graves, probably those of his immediate family. It is my hunch that the Columbo's may have perished from a sudden onslaught of the fatal pestilence, a deadly form of epidemic disease in those days from which people, especially Europeans are known to have died overnight in droves.

Epilogue:

It is most likely that Columbo Sahib was indeed a Portuguese, who may have come to Dhaka from Colombo, Sri Lanka or elsewhere. That he could have been a Dutch, cannot be dismissed outright. Since his peculiar Dutch name was perhaps difficult to pronounce, he probably came to be known in Dhaka as Columbo Sahib after the city of Colombo, from where he may have come. However, we cannot be sure of these speculations unless and until this riddle is finally solved by undertaking a thorough search of the archives in Calcutta, The British Library, the Hague and in Lisbon, to finally unravel the mystery of Columbo Sahib. It is also quite possible that even after all the suggested research have been conducted, his identity may still elude us. And, that he will continue to be known just as before, simply as 'Columbo Sahib' of Dhaka, thereby remaining an enduring enigma well into posterity.

This essay is dedicated to the memory of Aly Zaker (1944-2020), our beloved 'Chhotlu Bhai'. RIP!

Waqar A Khan is the Founder of Bangladesh Forum for Heritage Studies

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments