A Paean to Aleppo

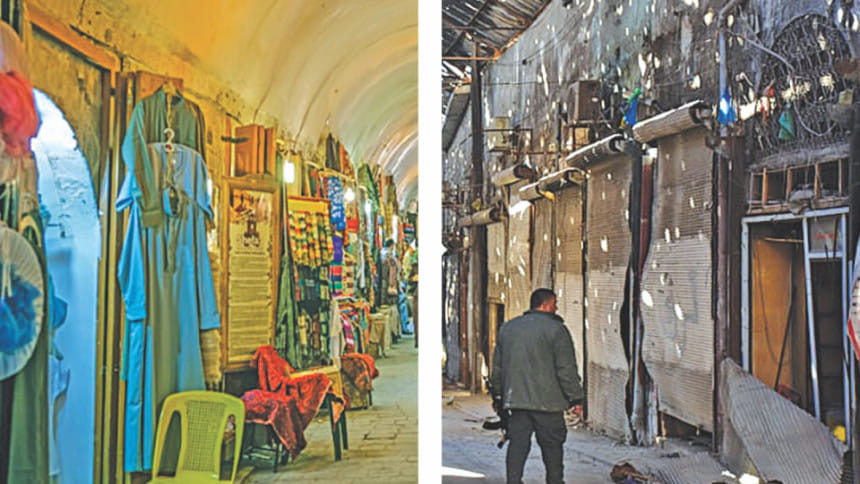

The heart-breaking visuals and devastating destruction that has befallen the citizens of Aleppo, its infrastructure and architectural heritage over the recent past has prompted me to provide the readers of The Daily Star with a personal travel account and perspective of the ancient thriving city and till recently – the modern thriving city of Aleppo. I want to share with you the cosmopolitan and diverse profile of the city's inhabitants. I want to tell you of the rich cultural mosaic of this historical bedrock. I feel it is my literary responsibility to present Aleppo in its yesteryears. For many today, Aleppo, Syria is just another war-zone. Just another civil war in the Middle East. Yet…

My book 'Fragrance of the Past: A Middle Eastern Itinerary' was published by Tara-India Research Press, New Delhi in 2007. The book explores my travels in Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. One of the chapters on Syria covers 'Aleppo: The Milky Way.' The trip was made in 2000. Other chapters on Syria include 'Bosra's Hidden Amphitheatre', 'Damascus: By Right the Eternal City' and yet another war-zone hitting the headlines in the civil war impacting Syria – 'Palmyra: 'The Bride of the Desert.'

In the Prologue to 'Fragrance of the Past: A Middle Eastern Itinerary', more than a decade later; I read with even greater remorse the following lines: "…for any traveller in the Middle East, the upheaval exists as a sad backdrop to a composite architectural and cultural legacy that is rivaled by few other regions and belongs to all mankind. Ultimately, it is the people and the land that speak and it is the fragrance of the past that endures."

Today, I lament. What has become of 'Aleppo: 'The Milky Way'?

Flying into Aleppo from Damascus, the barren beige landscape gave way to checkerboard patches of fertile cultivation. The soil appeared a rich reddish brown. I took it to be a positive indicator of the historical prominence and current prosperity of the city. Aleppo is Syria's second capital. Legend has it that the Prophet Abraham milked his cow on the hill that dominates the city. Hence we have Aleppo's Arabic name Halab al-Shahba, Aleppo: "The Milky White". The Syrian name for Aleppo is 'Halab'.

The Kingdom of Aleppo existed in the reign of the Akkadians around 3000 BC and the city boasts a history that long predates the advent of Islam. Aleppo has witnessed the sweep of history, every civilisation in the Middle East has added to its rich legacy; the Hittites, the Egyptians, the Sumerians, the Aramanians, the Cananites, the Persians, the Macedonians, the Seljuks, the Romans and Byzantines. The Arab conquest of Aleppo in 637 lasted approximately 900 years until the Ottoman Turk reign from 1516 to the end of the First World War. A period of French mandate followed. Syria gained independence in 1945.

Today's international boundaries situate Aleppo in northern Syria, close to Turkey to its north, Iraq to its east, Lebanon to its southwest and Jordan to its south. The city's unique strategic location has historically lent itself to its position as a thriving commercial centre at the crossroads between the Middle East, Asia, the Mediterranean and Europe. In ancient times, Aleppo reigned as a major commercial entrepot for regional and international trade -- a prominent halt along the fabled Silk Road connecting the East and the West. Testament to its international standing, innumerable remains of caravanserais dot the city. These stopovers provided necessary facilities to travellers and traders and were sources for the exchange and replenishment of stocks and products. It was a halt for weary merchants and their transport, be it camels or horses. Today's transport is more likely to be a massive four-wheel-drive vehicle. The transit complex could house a bazaar, water reserves, a mosque, a hamaam, a madrasah, offices, storage and accommodation. The caravanserais of yesteryears were the equivalent of today's hotel/motel, garage, petrol-station, bank, cafe, restaurant and travel agency.

European travel literature has mirrored the cosmopolitan element that is so apparent in this city. Aspiring and established entrepreneurs from Europe -- Amsterdam, London, Marseilles and Venice -- mingled with Armenian, Jewish and Muslim merchants. The Armenian presence in Aleppo is pronounced; Armenian villages of eastern Anatolia (Turkey) were early sources of immigrants to Aleppo. Aleppo's cosmopolitan culture attracted people from far and wide and the city's population reached its peak of about 120,000 inhabitants in the second half of the seventeenth century. Aleppo ranked as the third largest urban centre in the Ottoman Empire, after Istanbul and Cairo.

The Arab period saw the city flourish in terms of architecture, with the building of innumerable mosques, madrasahs, hamaams and souqs. A fortress on the central hill of Aleppo was built by Sayf-al-Dawla in 944. The Aleppo citadel stands in the centre of the city, 160 feet high. It was attacked by the Mongols in the middle of the thirteenth century and then again by Tamerlame at the end of the fourteenth century. The Mamluks added on to the indomitable citadel of Aleppo in the thirteenth century. Earlier civilisations dating back 5000 years had already built an edifice on the site. The citadel today, surrounded by a dry moat, rises abruptly from the midst of the teeming city.

We crossed the bridge over the moat and then crossed the first line of defence, the exterior thick wall of the massive citadel. The colossal wooden door with metal bars threatened to close behind us. We climbed up and down stairs and over the remnants of walls. There were towers that gave us a bird's eye view of the city and, in the depths of the towers, cold, dark and damp caves. There were elaborate hamaams, built separately for men and women, for steam baths, cold baths, rest rooms and tea-rooms. Aleppo's hamaams are renowned and about sixty of them are to be found throughout the city, some dating back eight hundred years. An enormous hall has been restored with an Arab interior complete with ceiling and walls painted in rich colours on panelled and carved woodwork.

Aleppo's status as a major commercial transit city attracted the first Europeans. At the end of the fourteenth century, Venice had appointed a vice-consul at Aleppo. The French and then the English in the second half of the sixteenth century followed suit. Yet the city also had to endure the Mongol invasion by Hulagu in 1260 and Tamerlame in 1401 when the city was pillaged and scores of people were killed or sold into slavery. In 1348, the bubonic plague decimated the population. Yet, again and again, Aleppo rebuilt itself and, each time, regained its primary role as a regional commercial hub.

ALEPPO: "THE MILKY WHITE""The day will come when one must part from you, city of Aleppo. |

By the time Ottoman rule had established itself in Syria in 1516, Aleppo was recognised as a thriving commercial centre. It is important to note that the Ottoman sultans regarded themselves as custodians of the Sunni Islam faith. The Haj pilgrimage passed through much of the Ottoman lands. The two major gathering centres for the pilgrims were Damascus for the Arab and Asian Muslims and Cairo for the northern Arab and African Muslims. In convoys consisting of thousands of people, humans and animals moved towards the Hejaz in present day Saudi Arabia. At a strategic crossroad, Aleppo was a key supplier of goods and services to the Haj pilgrims.

In these mass gatherings, commercial exchanges within the sprawling Ottoman Empire were both extensive and intensive. There was a large market within the empire for the transfer of foreign goods. It is said that in the Middle Ages 'one day's sale in Aleppo equalled a month's in Cairo.'

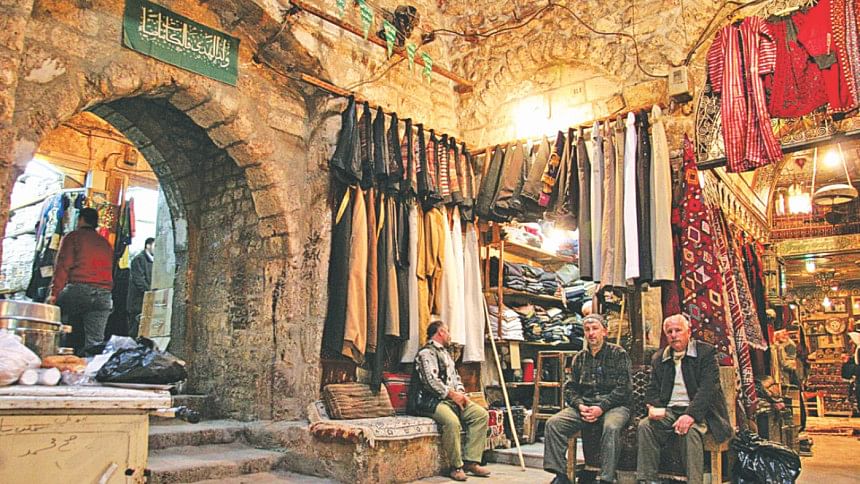

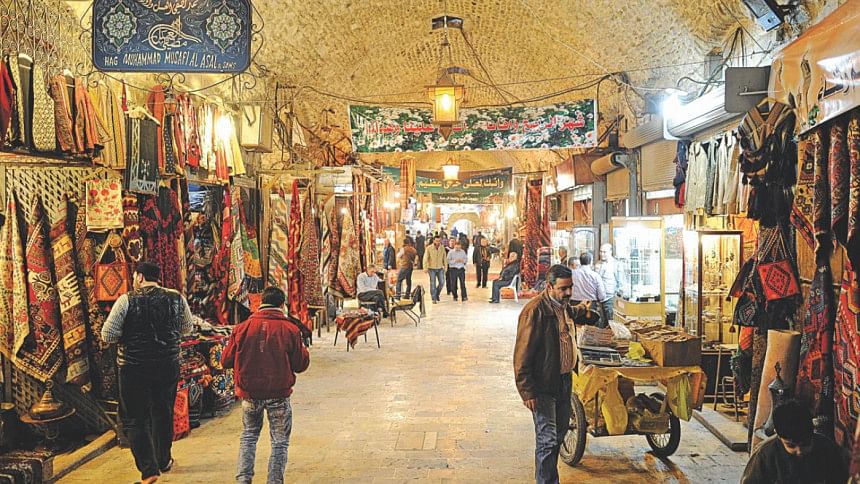

Our next visit was to the famed covered souqs of Aleppo that extend some ten kilometres and are located at the base of the citadel. The majority of the bazaars belong to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Many regard the Aleppo souqs as only second to Istanbul's Kapah Carsi (Covered Market). We found the souqs remarkably clean.

A renovated section of the central souq caters now exclusively to tourists. All the souvenirs one may want from Aleppo, Syria and even Iran, Turkey, Lebanon and Egypt can be found here; Iranian block-printed tablecloths, Turkish rugs, Lebanese glassware and Egyptian papyrus prints are some items sold among the range of products. This is the artisans' modern retail outlet, under one roof for the sake of convenience.

We strolled into a 'real' souq, a never-ending tunnel of bright lights further illuminated by the sunlight that glimmered through the roof-openings and vaulted window-openings and with everything under the sun to buy. I succumbed to temptation and we acquired a blue and gold brocade tablecloth -- an essential for survival! However, it was reassuring to know -- and it marginally eased feelings of guilt -- that Aleppo has always been known as a major silk trading centre. Iranian silk from the Caspian Sea region of Gilan, Turkish silk from Antioch and Bursa and silk from distant China had frequently changed hands in the textile souq where we had been bargaining for our purchase.

The souqs are named after their trade. Thus we have the cloth market, the gold market, the silver market, the shoe market ... Then there is the spice market where the various aromas from sacks of colourful spices waft by leaving a fragrant trail. Then there is the bazaar that stocks sweatshirts with "Harvard" printed across the front, Tex-Mex T-shirts, bland coloured track suits, shiny polyester dresses and trousers, and pink and yellow frilly nylon dresses that no child, I think, would like to be caught wearing. This souq is visually representative of today's international interaction.

We had a delectable dinner of Syrian/Allepine cuisine in a beautifully restored sixteenth century palace. Beit Wakil (Wakil's House) is located in the old district of Aleppo in a narrow alley paved with cobblestones. A recent private initiative to restore some of the old houses has resulted in the opening of a number of restaurants that have combined age-old architecture and tradition with modern amenities. Another 'new' restaurant named after the empress of Austria 'Sissi' looked most inviting as we walked by it. Adjacent to it is an Armenian school for girls.

Beit Wakil combines a fine restaurant with a hotel consisting of sixteen rooms. I asked about the occupancy rate, with the thought that it might be fine to dine in a sixteenth century palace but perhaps not to spend the night there, the manager replied that except for one vacant room (that he showed us), all the rooms were occupied. He led us upstairs, along wrought-iron balconies overlooking a courtyard and into a small but comfortably furnished room with Syrian woven fabrics and a newly attached bathroom -- perfectly cosy and inviting. Hotel Baron is a historical institution in Aleppo and well known among travellers throughout the Middle East.

We left Hotel Baron mesmerised by the long and extensive voyage through history and ready to hit any trail before us, armed with two gifts of modern carry-bags with 'Hotel Baron' discreetly printed on them. These bags accompanied us on many other travels within the region.

Raana Haider has a MA in Sociology from the American University of Beirut, Lebanon. Her most recent book 'India: Beyond the Taj and the Raj' was published by University Press Limited (UPL), Dhaka in 2013. The article has been abridged from the original.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments