REMEMBERING YASMIN

A 14-year-old girl got on the wrong bus on her way to Dinajpur from Dhaka. Upon realising her mistake, she stepped out of the bus, and was looking for another way home, when a police van stopped in front of her. A group of police officers got out and assured her that they would drop her home. Probably thinking that she could trust these protectors of the law with her safety, the young teenager got in the car with them. A day later her body was found by the side of a road, bruised and battered.

Yasmin Akhter was brutally murdered 20 years ago on August 24, 1995. And two of the three police officers involved in her murder were arrested two years later in 1997. While the delay in justice is definitely troubling, what's more worrisome is that nothing was done until the entire district of Dinajpur protested the crime, taking up arms, besieging a police station in the district for two days until the police opened fire against the protesters, killing seven. It took a massive people's movement for the government and the state to sit up and take notice of the crime committed by officers within a law enforcement body.

Unsurprisingly, the local police tried to block investigation processes and at first had even refused to lodge the case in an effort to save their colleagues and consequently, the "image" of their force – an image of an empathetic, duty-abiding body that jumps to the service of victims of crime that has so lovingly been held and preserved over the years. Women rights activists and the ordinary citizens of the country continued tirelessly to demand justice for Yasmin until the three policemen were finally arrested in 1997.

"This blatant act of blocking the investigation and creating barriers for justice to be served clearly shows how our society is shaped and reacts to violence against women," Ayesha Khanam, President of the National Women's Association, has said.

All three rapists and murderers were sentenced to death in 2004. However, before his hanging, Amrita Lal (driver of the police van) was absconding for a good many years before he was finally captured and his sentence was executed. The delay in bringing this perpetrator to justice, activists say, was because the police failed to carry out their responsibility.

In fact, police interference in the case was noticeable since the beginning. Instead of carrying out investigations diligently to prove to the public that their safety is the first priority for law enforcement agencies, the police and other administration forces tried to assert their dominant standing in society by asserting that no crime had taken place. At first, they refused to file a case. And then they tried to tamper with the evidence. During the proceedings, Advocate Zaed Al-Mamun had reported to the media that Yasmin's autopsy was first conducted by some civil surgeons of Dinajpur, who concluded that Yasmin was not raped. After continued protests and movements by activists and citizens, a board was finally formed consisting of principals of some medical colleges. "Her body had to be exhumed and it was finally proven that she had been raped," said Zaed. He further added that instead of being served with strict punishments so as to deter future tampering of evidence, the officials who submitted a false report were released after a trial.

Yasmin's death mobilised a whole movement that influenced a dialogue addressing violence against women. It brought attention to the flawed legal system of the country which took two years to arrest the perpetrators and almost nine years to execute their punishment. People from all over Bangladesh protested against the crime, united in their demand for justice. For the first time in the history of the country, policemen were tried and sentenced to capital punishment.

But 20 years after her death, Yasmin has more or less been forgotten. Most people don't even know the name of the young girl whose gruesome death provoked a mass movement and brought women's rights issues to the forefront. Most media houses ignore the day of her death while they observe the death anniversaries of "far more important dignitaries" of the country and the world. Few women's rights organisations carry out rallies in remembrance of her untimely death anymore. Yasmin, once a symbol of the fight against the powerful perpetrators of crime, is now shoved into the background, a lost name in the growing list of victims of unrequited lust and violence.

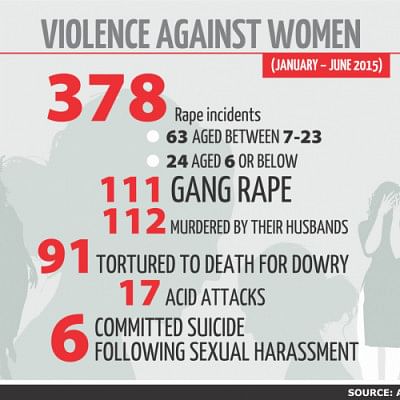

While it's always a struggle for a female victim of any crime – be it domestic violence, sexual harassment and abuse, torture, dowry related abuse – to receive justice, it seems that women from less privileged classes find it almost impossible to even demand justice, let alone get access to it. Even feminist discourses continue to focus on the abuse meted out to privileged women of a certain class, and stories of women belonging to poorer backgrounds are lost in the crowd of numbers and statistics.

And this leads to the next, more prevalent problem in our society – the denial of a rape culture. For those who don't know what this means, rape culture is one in which sexual violence is common, accepted, normalised, tolerated and even pardoned in a society. Rape is so common in Bangladesh that many feel only a slight annoyance or at worse indifference when they hear or read about such incidents. Rape jokes are common; we even hear songs glorifying violence against women, so it's definitely normalised and accepted in our culture. As cases time and again have proven, our society is more willing to put the blame on the victim for "inciting" sexual violence than on the perpetrator whose act is condoned only because he is a man with "natural urges".

A 2013 United Nations study based on anonymous interviews with more than 10,000 men aged 18 to 49 years from Bangladesh, China, Cambodia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Papua New Guinea showed that nearly a quarter of the men surveyed in this region have said that they raped a woman at least once in their life. Almost three quarters of those who admitted rape said they did not experience any legal consequences.

How shocking is that, really? If the chief of the Dhaka Metropolitan Police thinks that "a little jostling", "shoving" and "pushing" of girls by some "naughty boys" is nothing to be too worried about, why should we be surprised when rape counts continue to rise every year and criminals continue to be provided a shelter of impunity? The IGP had gone as far as to say that the "public should have arrested the miscreants." And when the public does try to wake the police and other authoritative bodies from their deep slumber of indifference, they are welcomed with sticks and guns, as evidenced by the seven people killed during the protests surrounding Yasmin's death. Or when their wrath was unleashed on the protestors who demanded the quick arrest and punishment of criminals involved in the Pahela Baishakh incident.

After Yasmin's rape and murder and the involvement of police officials in this case came to light, many, including members of the police force, were quick to assert that she was a prostitute, an "unchaste" woman whose life is of no consequence. Irrespective of the fallacy of the claim, this just goes to show how much importance we, an entire society, give to the sexual morality of woman, so much so that law enforcement agency could even think of giving this as an excuse as way of seeking pardon for its members.

When a rape survivor tries to lodge a complaint, she's besieged with intrusive questions that only serve to continue hurting the unclosed wounds:"Where've you been touched, show us the place, are you sure you were raped?"

Our culture is one that silently accepts the whipping of a 14-year-old rape victim for engaging in an "affair" with a married man.Teenagers like Yasmin, ten-year-olds, five-year-olds, even two-year-olds are brutally raped, and we still talk about women 'asking for it', as if a person would intentionally request to be sexually, physically and emotionally battered and humiliated.

Society normalises rape by humiliation and sanctioning violence against women in the name of social norms, says human rights activist and Executive Director of Ain O Salish Kendra (ASK) Sultana Kamal. "Family and the society are places where indoctrination and socialisation of patriarchal values nurturing principles of male hegemony over women – which motivates both men and women to accept it as natural – takes place. The socialisation process ensures men's control and disciplining power over women's body, mobility and labour," says Kamal.

Twenty years after the death of Yasmin and we still have to protest and sometimes plead for justice to be rendered on time to survivors and victims of rape and abuse. Thousands of Yasmins have been abused in the years following her death and the mass scale protests following it, their souls crushed, their voices unheard. Her death anniversary will probably just be another day for most of us. There will be some who will observe it, who'll place wreaths on her grave and give empowering speeches. But at the end what will all of this achieve? Yasmin is gone but her death should have served as a platform to not only launch a dialogue but actually realise a safe environment for women. Until our society, our law enforcers, the state, the government and the world at large begins to see women as actual human beings, not just as someone's mother, sister, wife, we will continue to see such heinous crimes being committed with latitude.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments