Rokeya's unrealised Dream

Feminism is considered an ugly word by many who have a passing acquaintance with it. An open assertion of being a feminist in social circles or even a betrayal of feminist sympathies will be met with incredulity, suspicion or disdain. That feminism is not a proclamation of women's superiority or a mandatory hatred for men, that it is the belief in equality of the sexes in every sphere, is often not acknowledged or understood.

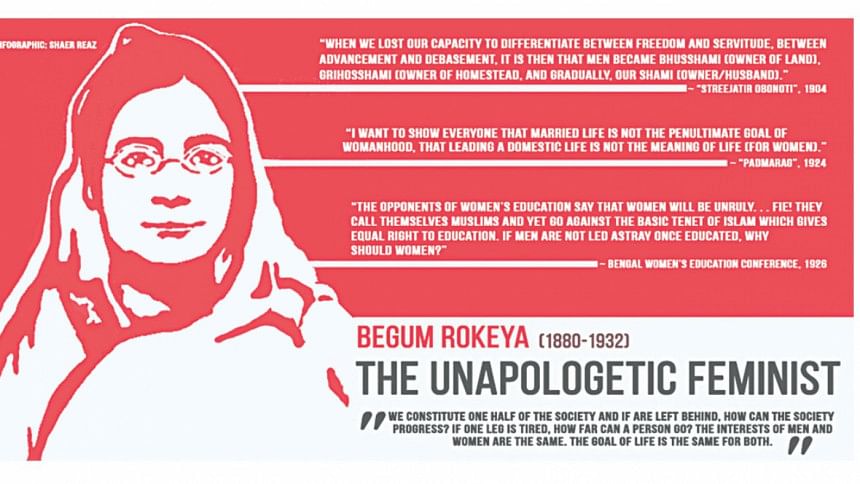

Ironically, amidst all the hostility surrounding the idea of feminism, we fail to realise that Begum Rokeya Shakhawat Hossain, a pioneer and hero for every Bangladeshi, was undoubtedly one of the first Bengali Muslim feminists of the sub-continent. Some scholars speak approvingly of Rokeya as someone who situated the discourse of progress for women strictly within the framework of religious patriarchy. Rokeya's lifelong work was, however, an implicit and often explicit criticism of this status quo. She wrote and campaigned in support of women whose needs were unmet by the male-centred and dominated socio-religious orthodoxy that was at the helm of the society she lived in. She addressed the issues of women's (primarily Muslim women's) confinement to narrow domestic lives in her writing, and rallied behind the cause of female education. She founded the Muslim Women's Association, offering poor Muslim women financial support, shelter and literacy classes. At a time when substantive education for women was frowned upon, Rokeya was one of the first to start a school for girls in the subcontinent.

Born on December 9, 1880 to a wealthy zamindar family in Rangpur, Rokeya was denied formal education by her strict, conservative family and was, in her own words, "locked up in the socially oppressive iron casket of porda" all her life. Rokeya and her sister managed to learn Bangla and English with the encouragement of their brothers. At sixteen, Rokeya was married off to Shakhawat Hossain, a widower several years older than her who supported the cause of women's education and encouraged his very young wife to keep reading, writing, and learning.

Rokeya's active interest in women's education and emancipation was initially met with disdain and heavy criticism. The girls of sharif (decent), well-to-do Muslim families could never be allowed to 'abandon' the respectable seclusion of their homes for 'wasteful' activities like education. In one of her notable speeches ("The Distressful Conditions of the Muslims of Bengal," Rokeya Rochanabali), she repeatedly apologised for 'bothering' people with the issue of her school, Shakhawat Memorial Girls School, but maintained that despite the risk of being labeled a nuisance, she would continue with the cause for the sake of future generations of the Muslim community. In her subtle, tongue-in-cheek manner she said, "I met a 'Brahmin Muslim' woman at the Bengal Women's Educational Conference who bluntly confessed that since girls in the Muslim community had no access to education, her father sent her to a Hindu school of great influence. Her education in a non-Muslim space resulted in her never having acquired the knowledge of the Holy Quran or Sunnah, and thus failed to adjust to Muslim society." She ingeniously played on the patriarchal society's bias for male children by asserting that lack of education for women did not just result in the waste of their potential but also 'derailed' Muslim men who wanted to marry educated women. "The Muslim society is paying a greater price for the lack of any system of education for their women. I have been informed by a reliable source that some educated Muslim youths of well-to-do families are setting conditions that if they can't find educated Muslim women, they will not marry. They even threaten to become Christians and marry someone from that community if they fail to find educated Muslim women." In the same speech, she argued that while other cultures and religions discarded their superstitions and borrowed Islamic laws such as a daughter's right to inheritance and her right to divorce her spouse, the Bengali Muslim society seemed to be giving up tenets of their beautiful religion and sound social system. Instead of haranguing the audience into accepting women's education on progressive or liberalist terms, she tried to win them over by playing on their fears of their children losing their sense of identity and community, and contended that the only remedy for this precarious condition would be to establish a school for Muslim girls, like her own school, where girls would be given a reasonable level of education so that men could marry educated women of their choice while girls could keep pace with the women of other nations.

Her iconic work Sultana's Dream, a utopian fantasy novella originally written in English, famously reversed gender roles. It tells the story of Ladyland which is run by women with the help of scientific knowledge and technological advances, while men are confined to the zenana, or as Rokeya terms it, the mardana. The novella begins with Sultana who seems to have been transported to a different world in her sleep, as Sister Sara, a native of Ladyland guides her through this new world order.

While explaining how women came to be in power despite being "naturally weak," Sister Sara offers the irrefutable logic that since men are "dangerous like wild animals," they must be locked up, while Sultana reflects that in her world, men who are capable of "doing no end of mischief, are let loose and the innocent women are shut up in the zenana!" Upon hearing this, Sara gently chides Sultana, stating that it is women who have neglected themselves and thus, "have lost [their] natural rights by shutting [their] eyes to [their] own interests." Calling the novella a "science fiction utopia" in her article "Feminism's Futures: The Limits and Ambitions of Rokeya's Dream" (October 10, Economic and Political Weekly), Rajeshwari Sunder Rajan writes that "there is poetic justice in the fate that men suffer as it is their own self-destructive aggression that brings them to defeat." Women don't use physical might but instead exercise their political and military power "wisely and with restraint," putting their scientific knowledge to the best use for the economy. Over a hundred years ago, Rokeya wrote about the ideal use of solar power to generate electricity and explained how nature and science can be used simultaneously for sustained growth. As Rajan writes in her article, Rokeya's utopia bears the "specific lineaments of science fiction – either the scientific fantasy of a world where science and technology deliver womankind (and mankind) from their condition of enslavement, or alternatively where women acquire and use scientific knowledge to transform the world."

Literalists might allege that Sultana's Dream was an act of literary revenge or an attack against the male sex, but I believe that Rokeya was attempting to portray an alternate reality in an ironic manner, presenting the absurdity of a hierarchy based on sex and gender. Rajeshwari Rajan argues that the writer could not "have been blind to the ideological implication of an idealised female ruler maintaining segregation and retaining the sexual division of labour while merely inverting it." Just as how women are rarely accorded the right to voice dissent or be heard and their issues are largely unseen by the male-controlled society in our world, men in Sultana's Dream are invisible, their voices are never heard; we don't get to know how they actually feel about their reversed role in the social order as the story presents men's narratives from women's point of view. In her reluctance to discuss the politics of the "reverse enslavement of men," Rokeya seems to reflect the apathy and discomfort in discussing the politics concerning women's rights in our patriarchal society. I would thus read Sultana's Dream as a destabilisation of gender, where the politicisation of gender rather than the sex of a person is the main problem.

Rokeya's critiques of shareef marriages question the dominion of men within this contentious institution. As writer and anthropologist Rahnuma Ahmed puts it in her article, Re-Reading Begum Rokeya (December 14, New Age), Rokeya "personifies the husband as the ruler", the korta or shami. In her novel Padmarag, Rokeya's protagonist Joynab spiritedly argues that even if she were to forget "all the insults and the neglect" that she endured and return to her domestic life, then "grandmothers and great-aunts will give my example to strong-willed young girls in the future and say, 'Forget all your pride and resolve. Look at Joynab! She has returned to a life of devoted service to her husband.' And men will exclaim with great pride, 'However high minded, strong willed, educated and noble a woman might be, she is bound to come back and fall at our feet.'" Joynab wants to set a different example to society as she seeks to let everyone know that "married life is not the ultimate goal of womanhood," that wifehood could not be the definitive aspect of her life. When Rokeya argues in Streejatir Obonoti that women's acceptance of "servitude" was the reason behind men becoming the shami or owner, you notice that her anger is not merely reserved for men, who have colonised women's mind and body as their property, but towards women themselves, who have accepted and accommodated this usurpation as the 'natural way of life.'

It's been 83 years since Rokeya's death; parents are still unwilling to send their daughters to school, fearing sexual harassment or violence; domestic violence and murder of women for dowry are common occurrences; women's lives are still conscripted by the choices and decisions of the men in their lives. Over a 100 years after Sultana's Dream was first published, the zenana still exists, not physically, but in the mindsets and attitudes of people. Over a century since Rokeya was born, a religious leader in Bangladesh crudely compares women to tamarind while another in India smugly declaims that women are fit only to deliver children and can't withstand crisis situations.

One would imagine that more and more people would by now realise that over 50 percent of the world's population lives in daily conditions of injustice and inequity. The facts about rape culture, lack of access to education, lower pay are available to anyone with an internet connection. But instead of anything resembling universal support, women are now beleaguered with accusations of a "war on men." Women who speak of equal pay or protections against sexual harassment are confronted with deeply vile terms like "femi-nazi" (as if the demand for a society where all people, regardless of gender, are afforded equal rights and dignity, were akin to perpetuating genocide). "Meninists" and Men's Rights Activists have entered the fray, armoured in misogyny and unchecked privilege. Some argue that feminists should instead call themselves 'humanists' if they actually believe in equal rights for all humans. The issue, which ought to be transparent to anyone with a grain of sense, is that the playing field is not level. A certain kind of human already has protections, and privileges built into the systems that govern our existence just by virtue of his anatomy and gender identity. Women are denied rights that men have enjoyed throughout history, and they are vilified now for asking for those rights, for daring to conceive of a world where their personhood is as valuable as that of a man. Feminism, or the recognition of (as Gloria Steinem put it) "the equality and full humanity of men and women," is still the call for the day. We still have a long, long way to go before Begum Rokeya's dream of gender equality is realised.

The writer is Sr. Editorial Assistant at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments