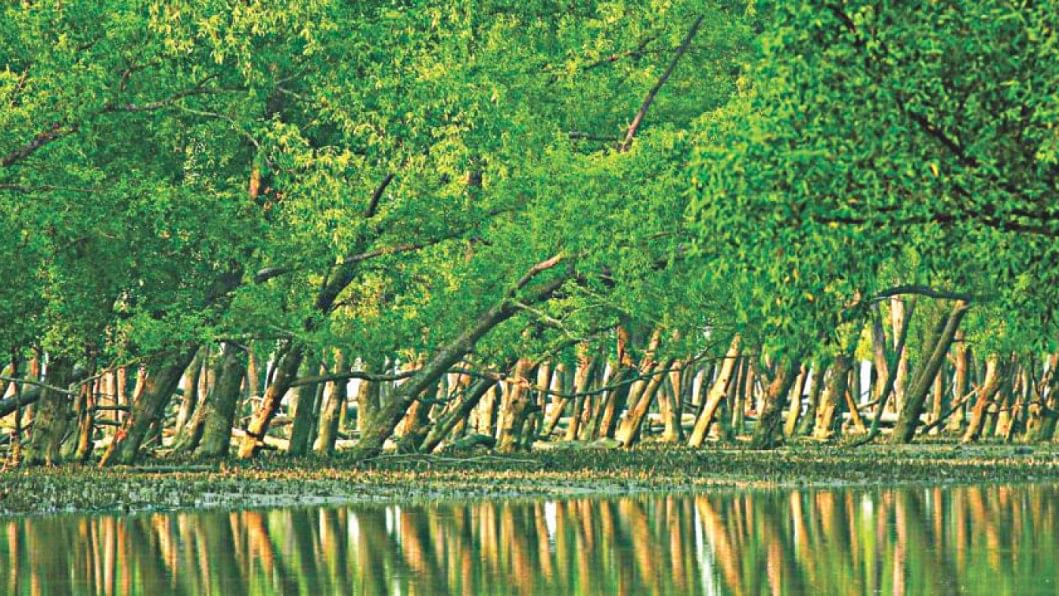

SUNDARBANS UNDER THREAT

Ask anyone, and they can tell you that you cannot put a price on the Sundarbans. The people who live in and around the Sundarbans, those whose lives depend on it, can tell you, even without a degree in environmental science, that the mighty mangrove forest, which provides for them and protects them from natural disasters, is an irreplaceable asset. They'll tell you, as will environmentalists anywhere in the world, that there simply is no alternative to the Sundarbans, though there may be many alternatives to power production.

And yet, barely 14 km away from the edge of the world's largest mangrove forest, construction work is going on for a 1,320 MW coal-fired power plant in Rampal. The mega-project is being implemented by the Bangladesh-India Friendship Power Company (Pvt.) Ltd, a joint venture of the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) and National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) of India. Incidentally, no such plant can be set up within 25 km of a preserved forest, animal sanctuary or bio-diverse forest in India.

The government has consistently claimed that the power plant would cause no damage to the Sundarbans, despite expert opinions to the contrary. Local environmental groups, including Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon (BAPA), Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association (BELA), the National Committee for the protection of Oil, Gas, Natural & other Resources (hereby called National Committee) and the National Committee for the Protection of Sundarbans, have all vociferously protested the government's proposal since the bilateral project was announced. Meanwhile, international bodies, such as the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, Ramsar Convention Secretariat, and International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Bangladesh, have formally expressed their concerns over the grave threats posed by the proposed power plant to the Sundarbans and urged the government to review their position.

Only last month, three French banks refused to invest in the Rampal power plant for the risks it posed to the critical ecological area. Bank Track, a coalition of organisations tracking the financial sector, declared in its report that there were "serious deficiencies in project design, planning and implementation" and that the failure to comply with minimum social and environmental standards and the corresponding financial risks made the project a clear "no-go" for financial institutions. The report called on signatory banks "to publicly rule out involvement in financing or support of any kind for the Rampal coal plant." Six months earlier, two Norwegian pension funds pulled out their investments from NTPC for the same reason. The Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global's Council on Ethics, after conducting a thorough investigation, recommended divesting from NTPC "due to an unacceptable risk of the company contributing to severe environmental damage."

With 70 percent of the project to be financed from loans and 15 percent by India and Bangladesh each, the financial viability of the project – or a lack thereof – is a reality the Bangladesh government must confront, sooner or later. "We also must remember that it is Bangladesh which will have to pay back the loan and interests. This means that though Bangladesh has a 50 percent ownership of the project, it is financially responsible for 85 percent of it. In case the power production is stopped, Bangladesh will have to bear the cost of the entire loss," informs Dr Abdul Matin, general secretary of BAPA.

Under the circumstances, instead of re-evaluating the environmental and economic feasibility of the project and relocating to a different site before construction work proceeds, the Prime Minister, on June 29, once again made it crystal clear of her government's unequivocal support of Rampal. Insisting that she would not have approved the project if there were any risks to the Sundarbans, she added, "I don't believe that others will have more kindness to save the country as well as saving Sundarbans. It is like shedding crocodile tears."

A FLAWED EIA

The premier's assurances would have been comforting had it not been for her government's consistent downplaying of the potential environmental cost of the plant. Environmental activists have even raised questions about the legitimacy of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for this project, rejecting its findings for being biased, distorted and inaccurate. It is telling that the EIA for this project was approved by the Department of Environment (DoE) on August 5, 2013, but land acquisition began two years earlier on August 23, 2011, and the joint venture between NTPC and BPDB was signed on January 29, 2012.

"That work on the project began long before the EIA was approved only goes to show that it was done as an eye-wash to justify the project. How can a bilateral agreement be signed when the environment impact hasn't even been completed?" asks Prof Anu Muhammad of Jahangirnagar University, also member secretary of the National Committee. "The inconsistencies of the EIA are apparent, even on a cursory glance through the document," he adds.

Dr Abdullah Harun Chowdhury, Professor of Environmental Science of Khulna University, charts numerous reasons as to why he considers the EIA to be flawed. "It would take a whole class to outline the flaws, but to name just a few – it uses secondary data collected before 2010 for most of the parameters; it fails to use proper location and methodology for primary data collection of air, water, soil, biodiversity; it compares sulphur oxide (SOx) and nitrogen oxide (NOx) levels in the Sundarbans with that of urban areas, as if Sundarbans is an urban area, and not an ecologically critical area!" he says.

"Without specifying which country the coal will be imported from and its quality, the extent of damage from the coal cannot be assessed by an EIA, making the current assessment flawed," argues Prof Muhammad.

In addition, the EIA does not adequately assess the factors and risks related to transport and disposal of coal ash, waste management and water requirements for operation of the plant. Additionally, say experts, it minimises the impact of the proposed plant on the livelihoods of the people who depend on the Sundarbans and the Passur river.

Notably, the organisation that conducted the EIA, the Centre for Environmental and Geographic Information Services (CEGIS), is not a non-partisan organisation, but rather a government-owned one. "The extent of its 'objectivity' can be deduced from the fact that the acknowledgement section blatantly praises the 'visionary thinking' of the energy advisor and admits to receiving 'instructions' and 'guidance' from the government," says Dr Matin.

According to the EIA Guidelines for Industries 1997, public hearing and public participation must be ensured during the environment assessment. However, according to citizens groups who were called at a consultation meeting following the publication of the EIA report on BPDB's website, the public hearing was conducted in name only, for the objections and recommendations of the groups were not included in the final document.

"We were consulted in a one hour meeting and, in the end, our feedback wasn't incorporated anywhere," says BELA Chief Executive Syeda Rizwana Hasan. "On the contrary, when organisations with international legal mandate to work on conservation issues objected to this project or raised concerns, the government either opted to remain silent, or probably addressed the concerns in a very unscientific manner and without substantiating its stance."

According to activists of Khulna, Bagerhat and Rampal, the opinion of the locals and affected people were also not taken into consideration at any point of the project design and implementation, even though the EIA states that different groups of people, including farmers, fishermen, development workers, activists etc. were consulted. Activists claim that most people who were invited to the views exchange meetings for the EIA were in the pay-check of the ruling party and did not reflect the people's concerns.

Although the DoE approved the EIA, it did so with reluctance, after rejecting the document numerous times over the course of three years. According to a higher-up at the DoE, the department was under tremendous pressure to approve the EIA. "If you look through our meeting minutes, you will see just how many times we objected to the EIA document and asked that it be reviewed again. Ultimately, we were compelled to approve it, but we did so conditionally, stipulating 59 terms. I believe that if the company meets all these stipulations, it would no longer be an economically viable project," he says, under conditions of anonymity.

Sharif Jamil, Council Member, Waterkeeper Alliance from Bangladesh, says, "It is not difficult to imagine the kind of pressure the DoE was under. It is also perhaps no coincidence that the then Director General of the DoE was promoted as the Secretary to the Ministry of Power shortly after the EIA was approved."

AT WHAT COST?

Much has already been said and written about the multifarious damages posed by the coal power plant to the environment. For instance, the coal fuel for the power plant will be transported through waterways in Sundarbans, which will cause heavy waterways traffic through this ecologically-sensitive Passur river (a sanctuary of Ganges river dolphins, Irrawaddy dolphins and river turtles); the wastes, sounds, waves due to the movements and light pollution will destroy the habitats, and any accident or spillage will cause an ecological disaster. Incidentally, no independent EIA has been conducted on the transportation of coal through the Sundarbans, even though it was one of the 59 conditions set by the DoE. The severe sound pollution from the operation of the plant, from the turbines, generators, compressors, pump and such will affect the wildlife, as will other activities like dredging of rivers. Again, no EIA has been conducted to evaluate the extent of damage such extensive dredging of rivers would cause.

Experts note that acid rains and inhabitants' lung diseases will be caused by the sulphur and nitrogen gases produced during the operation of the plant. Solid and liquid wastes from the plants will also infiltrate the river and canals, and spread further into the Sundarbans.

Several lakh people are being directly affected by this power plant, as their livelihoods depend on the Sundarbans. About 8,000 people of 40 villages in Sapmari, Koigordas and Katakhali moujas have allegedly already been severely affected, with many losing their arable lands to the acquisition.

According to the government, 156 families were displaced by the land acquisition process, but locals claim that the number of families affected was significantly higher. Shushanto Kumar Das, a victim and a member of The Committee for the Protection of Agricultural Land, claims, "3,500 land owning families, who were directly affected by the acquisition, submitted written applications to the District Commissioner stating that we objected to the acquisition. Another 400 landless families lived and worked on the land, all of whom have now been driven off."

He also notes that every year, this area produced fish, paddy, meat etc. worth millions of taka. "But now all our livelihood opportunities are gone along with our paternal homestead lands. The workers who worked on the shrimp farms or agricultural lands have lost their employment as well."

The landowners in the villages state that the compensation they received was insufficient (BDT 270,000 per acre) and much lower than the market price of equivalent land in nearby areas (BDT 500,000 – 700,000 per acre). The landless people who were dependent on this land received no compensation.

Abdul Rajjak, an affected villager who lost 5 acres of land, says, "The compensation they gave is just not enough for a family to relocate to a different place and start a new life. I don't have any skills to get a job anywhere at this age, and with no agricultural land to cultivate anymore, I am struggling to feed my family."

Locals fear that once the project is completed, more people will be displaced and lose their livelihood opportunities. "For us, Sundarbans and the surrounding rivers are our lives. But they want to dump wastes in it, pollute it, kill our fish and vegetation, and then, when we're out of jobs, dangle jobs at the factory in front of our noses," says a frustrated Jahid Hasan, also a victim. "We don't have any hopes that we'll get jobs in the plant"

The 1,320 MW coal based power plant is supposed to hire 4,000 people for construction purposes and 600 people once the plant is operational. Jamil, also joint secretary of BAPA, argues, "The workers who would be hired by the project are mostly skilled workers, but the people of the area are farmers, fishermen or manual labourers. How many of them will get jobs in the end when the plant is operational? In fact, as outsiders move in to get these skilled jobs, more locals will be displaced."

Local activists and villagers state that they have protested the land acquisition process – which, they claim, was done without following due process – and the Rampal project since 2010, but the authorities have not paid heed to their protests. Instead, they have been constantly harassed, threatened and assaulted by powerful quarters; and false cases have been filed against six of them.

"The authorities have cracked down on protests organised by different groups, declaring Section 144 to stop us from gathering, and beaten us with the help of law enforcement and thugs. They've threatened to make arrests if we showed up at protests. An activist's house was set on fire. Many people who were with us in the beginning are now afraid to speak up, as they and their families are specifically targeted by the powers-that-be if they are too vocal," Forrukh Hasan Jewel, an activist from Bagerhat.

WHO DO WE TRUST?

The people's protests have, thus far, fallen on deaf ears of the government, which insists that no environmental laws or regulations will be flouted in the process of establishing the plant. The government has also stated that it trusts NTPC to follow up on its promises to maintain the environmental standards and protect the Sundarbans. But why, one may ask, are we trusting this entity called NTPC and what does it stand for anyway?

In a recent study conducted by the Centre for Science and Environment in India, NTPC was considered the worst polluter in an objective performance rating for 47 Indian coal-fired power plants. The study claims that the Indian company was secretive and non-transparent in its operations, and that it hid its poor operational record from the research organisation. The report also mentions that Indian plants fell well below global performance benchmarks for efficiency and pollution controls in comparison to coal plants elsewhere.

"The study is certainly worrying because it clearly shows the kind of company the government has chosen to trust. If their track record is so poor in their own country, why should we believe that it's not going to be worse in Bangladesh, a country where there is such poor environmental governance and monitoring?" asks Rezwana.

Environmentalists across the board believe that the coal power plant should be relocated without any delay. Although the project is underway and construction work has begun, the cost of relocating would be insignificant, they argue, to the cost to the Sundarbans – and to Bangladesh at large – if we go ahead with the project.

But with the government refusing to see or hear no evil, who are we to turn to, to protect our Sundarbans from the imminent threat of destruction?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments