The Burden of Dis/honour

Reena's parents were shot by the Pakistani army in front of her eyes. She didn't know where her brothers were, or even if they were alive or dead. She herself was taken by the same men who killed her parents, and first kept by one army officer, then later made to serve several in a camp with 20 other women, repeatedly raped for almost six months. But at the end of it all, it was Reena who was regarded with curiosity at best, disgust at worst. After the war ended, Reena had even decided to go to Pakistan, for she felt there was no place for her in Bangladeshi society, but her brothers who, as it turned out, were alive, found her and brought her home. When she finally got up the courage to go back to university, her classmates distanced themselves from her. When her fiancé returned from abroad, though he agreed to marry her secretly and take her abroad with him, he was clearly not comfortable with the idea. Reena knew that, though he may be a good person, he did not have the strength to bear her burden and courage to do so publicly and she released him from their relationship. She finished her education, worked for some time, and later, married a man who respected her, understood her ordeal, and honoured her sacrifice. She went on to have three children and a fulfilling life.

Reena's is one of the several stories documented by educationist, writer and social worker Nilima Ibrahim in her book Ami Birangona Bolchhi, published in the 1990s, based on her work with the survivors of wartime sexual violence in post-conflict Bangladesh. These as well as other stories – though official documents were destroyed after the war – attest to the atrocities committed against women in 1971.Official and unofficial estimates claim that between 200,000 and 400,000 women were raped. Several of these women committed suicide, some left the country after the war, others moved on with their lives in physical and emotional pain and secrecy. Many women were left pregnant as a result of the wartime rape, with there being at least 25,000 documented cases of abortion, while many other "war babies" were put up for adoption. As Susan Brownmiller documents in her seminal work from 1975 Against Our Will: Men, women and rape, the first to bring the case of Bangladesh to international attention, girls and women aged eight to 75 were raped, Hindus and Muslims, irrespective of class, caste, anything at all except their gender. After the war ended, Bihari women were also violated by the Bangalee population as a means of avenging the wartime violence against Bangalees in which many Biharis supported the Pakistani side. Both narratives are veiled in silence for the most part. This goes to show that despite the honorifics of the title of "Birangona" accorded by the state to the survivors of sexual violence after the war ended in December, the women remained marginalised – by their families, their communities and the society at large. According to researchers, some women have actually claimed the Birangona title to be their "greatest sorrow". This identification/isolation/singling out of their experience made it even more difficult for women. Reena was one of the relatively lucky ones; many women were not accepted by their own families – parents or husbands. Those who attempted to reintegrate into society did so without ever talking about their experiences, as if it was they who were at fault. Some women to this day live around neighbours who handed them over to the Pakistani army in 1971. While the state may have had a good intention in declaring the women war heroines, the reality in which they lived was not ready to accept them except as victims or, even worse, as ruined women, with the label adding to the burden of their already unbearable trauma of the war.

The history of rape in wartime is said to be as long as the history of war itself, but for the longest time, it has been treated as an unfortunate byproduct of war and it was only beginning in the 1990s, following mass rape during the conflicts in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, that rape as an actual weapon of war started to receive policy, media and scholarly attention and the systematic use of rape in warfare was defined as a war crime.

The causes, strategies and forms of wartime sexual violence have varied in different contexts, playing a major role in some, minor in others and none at all in certain conflicts. Because of physical differences between women and men, but also because of the differences in cultural meanings ascribed to male and female bodies, women and men are abused and tortured differently and die different deaths. Women, who are seen as carriers of cultures, bear the brunt of it for several reasons – from an "ethic of purity" which legitimises the cleansing of internal enemies of the state as well as aliens on the land, to being an effective way to strike at the honour of the nation (motherland) and humiliate its men. The official sanctioning of rape by officers in order to promote soldierly solidarity through male bonding and the booty principle, whereby, along with the conquered territory, the victor in any war also wins the right to (violate) the enemy women, serve to further institutionalise the crime.

In extreme cases, such as that of Bangladesh and Bosnia-Herzegovina, rape has been used as a tool of ethnic cleansing, to either impregnate women so that they bear the "enemy's" children, or to prevent them from becoming mothers in their own communities by making them socially unacceptable or physically unable to bear children. Even as the Pakistani army was surrendering after the nine-month-long war, some of its members claimed to be leaving their "seed" behind in the Bangalee women they had impregnated. Their deliberate policy to demoralise, dehumanise and destroy the enemy largely succeeded, for they did render many of those women unacceptable in Bangladeshi society. In the case of the war babies, some of the women themselves did not want to have or keep the babies, while others were compelled to abort or put them up for adoption as the state did not want "polluted blood" in the country, with national leaders also claiming that the children would lead better lives abroad.

The Birangona title was heroised in post-war Bangladesh but the Birangona herself remained a cause for shame and secrecy. As many Birangonas have observed, they are not the ones commemorated on national occasions, or who roads are named after, or who are even treated with dignity and respect. It is only in recent years that we have begun to hear about our war heroines, that they have become the subject of academic research, newspaper features and television dramas. But it is still rare to find a woman who will proudly declare herself a Birangona – not because she does not comprehend her contribution to her nation's freedom but because her country does not value and honour her sacrifice.

The demand of rights groups for decades has been the according of the title of Freedom Fighter to the Birangona, and in October of last year, the government for the first time bestowed the title of Freedom Fighter and its associated facilities and benefits to 41 war heroines. The list still remains separate from that of the original list of freedom fighters, and the process of selecting women for this list – based on the Birangona filing applications which are then scrutinised and approved by local authorities – is ongoing. This March the Parliament has passed a proposal to include Birangonas in the list of freedom fighters.

It has taken us almost half a decade to just begin to recognise the sacrifice of women who fought a different war with their bodies in our struggle for independence and who to this day live with those wounds, physical and psychological. For as long as women's bodies are the site on which violence and power are inscribed, they will continue to be violated in peace as well as wartime, and for as long as the victim of rape and not the crime is stigmatised, women will not be secure, let alone respected, in society. Rape in wartime must be treated as a war crime, with appropriate legal proceedings against the perpetrators, and reparations – as much as is possible in such cases – made to the victims/survivors. This includes their rehabilitation and social reintegration in the true sense, not in shame and secrecy, but in acceptance and with respect.

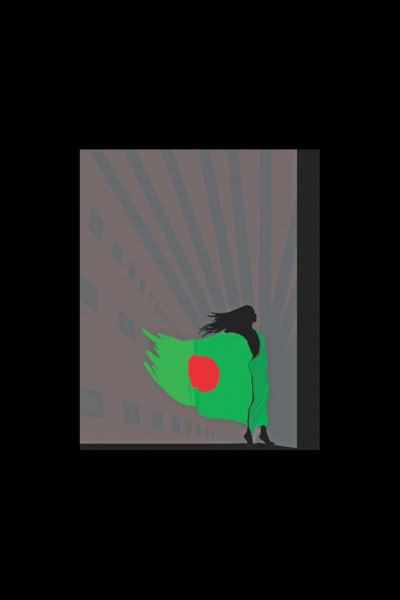

Reena's tale ends with the realisation that, despite getting everything any woman could want in life, there remained an emptiness, a lack of fulfilment inside her. This void could only be filled, she felt, by the respect of the youth of this generation, of her recognition as a freedom fighter, as one who claims to be a part of the nation's flag, whose voice reverberates in the national anthem, who has a right to the country's soil. This is the hope that Reena had clung to all her life.

This is the least, and perhaps the most, we as a free nation can do for the Birangona who is yet to be liberated.

The writer is Assistant Professor, University of Dhaka, and a doctoral student at SOAS, University of London.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments