The post throughout the ages

The generation of the '90s would fondly remember that creaky, static-y sound of a 14K modem; the screech, like music to their ears! The joy of finally getting connected to the World Wide Web after frantic efforts lasting 30 odd minutes, through an ailing analogue landline, or the sheer terror of someone picking up the phone while this process is ongoing, is something only that generation can relate to. The youngsters of the '90s witnessed the world getting smaller, communication getting faster, and some might argue—the demise of the post office.

Communication between civilisations of the past, and between modern nations in present times, is one of the biggest achievements of the human race. Looking back at the annals of Indian culture, we find poets musing on couriers in the form of the clouds or swans. The use of homing pigeons to transmit messages is a regal lore of the Mughal dynasty, and quite astonishingly, is still used in some remote regions of India.

History records well-established, functional postal networks as early as 500 BC. Herodotus c.484 BC, was so impressed by the Persian system of mounted postal carriers, that he wrote:

"Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds."

In the Indian subcontinent, the development of the organised postal service can be dated as far back as the reign of Sultan Qutubuddin Ibek, the first Sultan of Delhi in 1206-10 AD. Modelled after the Arabian administrative structure, a network was maintained from Delhi to Bengal, but it was not until Sher Shah Suri (1538-1545 AD) that the significance of a well-maintained communication link was realised.

He established a mounted post by improving the early dak runner system, and constructed the grand trunk road from Sonargaon to the bank of the river Indus, covering a distance of 4,800 kilometres.

Emperor Suri's postal system was based on a self-centred policy and solely for governance of far-flung regions of his empire. The service was strictly designed for the Durbar.

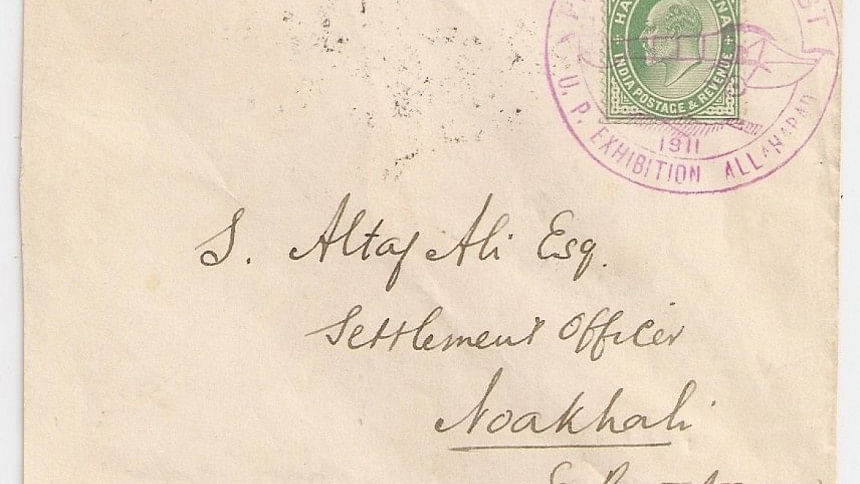

Even during the Mughal rule of India, European merchants had their own "self-centred" communication line. Mail to their respective countries were carried on naval ships or merchant vessels. As the East India Company gained more and more control across the subcontinent, other "aspirant" European colonialists shrunk their activities, with shattered hopes of making a colony in the East.

It must be stated that none of these postal networks running over a millennium had any impact on how commoners communicated. Literacy rate was low, and people wishing to write letters mostly relied on village scribes—a person held in high esteem in early societies. Letters, like these, were carried by travellers, either as favour or a small token of appreciation. In most cases, messages were just transmitted verbally.

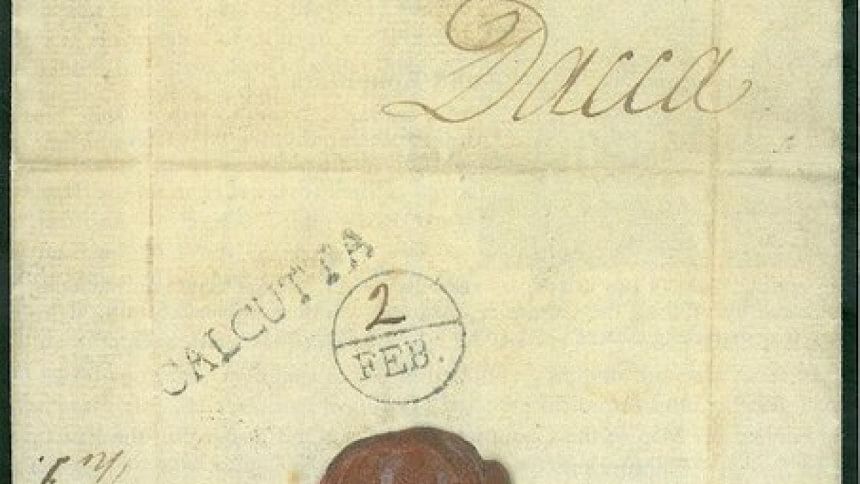

In 1766, the first reform in postal service was introduced by Robert Clive. A postmaster was appointed in Calcutta, which was connected with six mail routes. The main connection was with Dhaka and Patna. This system was known as Clive's Post.

Although the problem of inland mail routes was somewhat solved, mail to international destinations was a problem. Some were carried in exchange of money, but postal tariffs were not released. However, it is wrong to assume that no transcontinental routes existed. The biggest impediment of those times was the fact that nothing was organised and planned.

Transmission of mail between different nations posed difficulties and the solution primarily depended on bilateral or, at times, tripartite agreements. Not only were the contracts cumbersome, at times mail had to route through perilous conditions, when a simple agreement between certain countries could provide a global solution.

"The Universal Postal Union is a specialised agency of the United Nations (UN) that coordinates postal policies among member nations, in addition to the worldwide postal system. Bangladesh became a member of the UPU on February 7, 1973. The purpose of World Post Day is to bring awareness to the Post's role in the everyday lives of people and businesses, as well as its contribution to global social and economic development. UPU member countries are encouraged to organise their own national activities to observe the event, including everything from the introduction or promotion of new postal products and services to the organisation of open days at post offices, mail centres and postal museums.

It was not until the creation of the UPU on October 9, 1874 that the chaotic situation was brougt to acceptable terms. And to mark that significant day in world history, since 1969, October 9 is observed as World Post Day.

The Post Office, many believe, has lost its importance. In utmost certainty the "romance" is gone. The culture of sending that "blue letter" is now a nostalgic remnant found only in works of fiction.

While this may be true from a personal point of view, as we prefer to send emails rather than scribble on a postcard or send a heartfelt greeting card—a simple message in social media suffices for most people.

Yet, for a country like Bangladesh, an emerging tiger in terms of economy, business opportunities are now more widespread than ever. While negotiations between parties now take place over Skype, the traffic of industrial samples is still a big market, and shall continue to be so in the foreseeable future.

However, the Bangladesh Post, along with all postal services run by other governments, face severe competition from rival private services, both home and abroad. And there is no iota of doubt that as far as the quality of service is concerned, the private couriers are much quicker, and far more efficient than the Bangladesh Post.

Yet, all hope is not lost. Philately, once a major source of income for various postal departments at one time, can be revived to recoup some of the losses that the Post Office now incurs on a yearly basis.

The world's first postage stamp was released on May 1840 in the UK. It cannot be established how the hobby went "viral", but within the next two decades, Victorian society was immersed in an obsession of collecting stamps. Post-1900, till the beginning of World War I, was the zenith for philately as a pursuit. Stamps issued by countries not only served the postal purpose but also made way for some additional revenue from collectors.

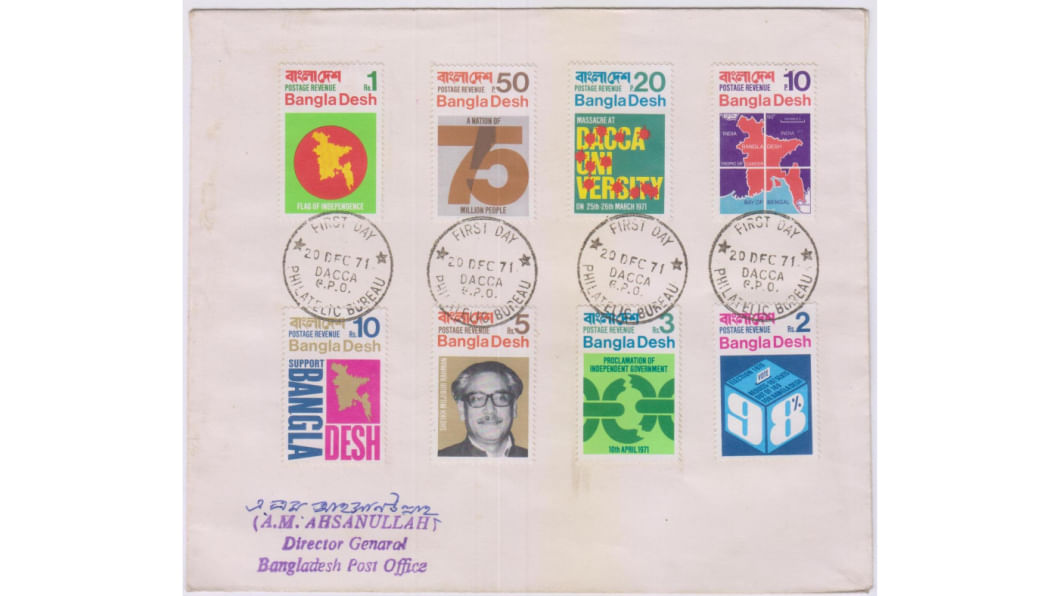

Bangladesh issued its first postage stamp on July 29, 1971. Designed by a Bengali artist, Biman Mullick, the idea for issuing the stamp was put forward by John Stonehouse MP, a former Postmaster General of Royal Post, UK, to the Mujibnagar government in exile.

Such a move, Stonehouse believed, would help create a widespread response within the global community and the money collected through the sale of this stamp could also be a valuable additional to the Mujibnagar treasury.

After December 16, 1971 the Directorate of Post and Telegraph resumed work with A M Ahsanullah, as the Director. It must be mentioned that the subsequent decisions taken regarding the sale of these Mujibnagar stamps (a topic beyond the scope of this article) by Ahsanullah and the ministry concerned, remain testament to the foresight and zeal of officials to create a new nation full of hope and glory.

Since independence, Bangladesh had maintained a conservative stamp issuing policy. The selection of theme, the designs, and even the production of stamps was able to attract a wide number of collectors at home and abroad. The first Bangladeshi philatelic exhibition was held in 1973 and played an active role in promoting Bangladeshi philately to the world.

Yet, some wrong moves and lack of enthusiasm from the postal authorities, and collectors themselves have resulted in an ever-shrinking world market. What is more alarming is that even established collectors are now shying away from continuing with their collection.

A group of local collectors have, over the last one and a half decades, participated in various international exhibitions, some achieving prestigious awards. These however, are personal achievements. To ensure a revival of philately in Bangladesh, the post office should patronise exhibitions, seminars and workshops; philatelic societies and associations too should shrug off their lethargy and promote the educational and creative aspect of the hobby.

Philately can be a useful means of garnering revenue for the postal department and can also provide young people alternatives to engage themselves in beneficial pursuits than the ills that now surround society at large.

Mannan Mashhur Zarif is a Sub-editor at The Daily Star and a philatelist.

Comments