I have not come to weep

In her memoir, translated into English as An Unknown Woman (2016), Jowshan Ara Rahman describes how the first poem on February 21, 1952 came to be written. Mahbub Alam Chowdhury, to whom she was engaged to be married, was the editor of the Chittagong monthly magazine Shimanto and the convener of the Chattagram Zilla Sorbodoliyo Rashtrabhasa Sangram Parishad, the all-party National Language Movement of Chittagong District. On the night of February 20, 1952, Mahbub, while working in the office of the Rashtrabhasa Sangram Parishad, came down with chicken pox.

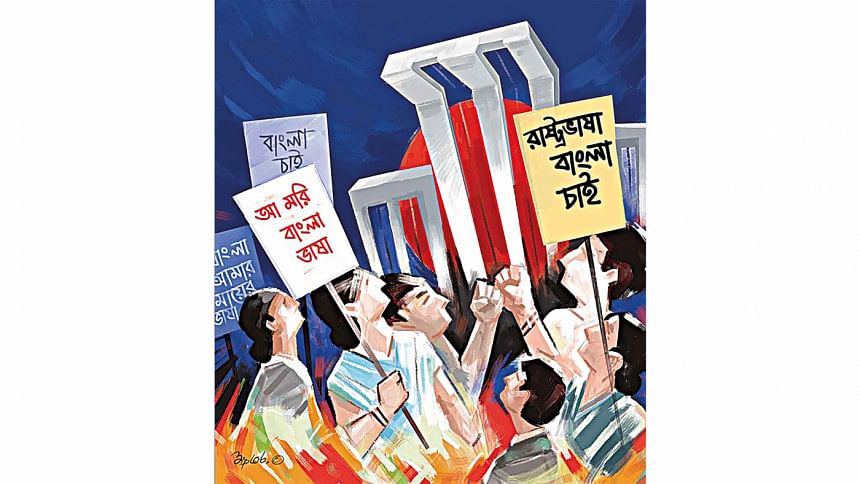

Late on February 21, the news of the police firing on students in Dhaka reached Chittagong. Despite his high fever, Mahbub composed a long poem dedicated to the language martyrs: "Kandte ashini – phanshir dabi niye eshechhi" (I have not come to weep but to demand the gallows). That same night, copies of the poem were printed. A day or two later the poem was read out at a public meeting at the Laldighi Maidan.

Mahbub's incendiary poem was confiscated and all available copies destroyed – though, as it happened, a police officer gave a copy to his sister, asking her to copy it down in her khata. This would later be recovered and the poem printed in its entirety. Meanwhile, fearing that he would be arrested, Mahbub was able to evade the police by fleeing in a burqa.

What was there about Mahbub Alam Chowdhury's poem that aroused the anger of the authorities? Perhaps because it demanded capital punishment for those who had shot and killed the protestors demanding Bangla as the state language. Perhaps because the number of deaths attributed to the police firing might incite further protests. As far as is known, there were five persons who died in the police firing that day: Rafiquddin Ahmed, Abdul Jabbar, Abul Barkat, Abdus Salam and a young boy named Ohiullah. Shafiur Rahman succumbed to his injuries the next day.

It is thought by many even today that there were others killed as well in the police firing but that the bodies were hastily removed and buried. However, the number of forty in Mahbub's poem has not been corroborated by anyone. Using whatever information he got – some of it incorrect -- Mahbub wrote this moving poem. For example, he wrote about women being killed. Though women were in the procession – in fact, women were the first to emerge from the university campus – there is no record of women being killed that day.

Despite this misinformation, Mahbub's poem is powerful, demanding justice for those killed even while mourning the loss of young lives.

I have not come where they laid down their lives

under the upward-looking krishnachura trees, to shed tears.

I have not come, where endless patches of blood

Glow like so many fiery flowers, to weep.

Today I am not overwhelmed by grief,

Today I am not maddened with anger,

Today I am only unflinching in my determination.

Translated by Kabir Chowdhury

The poet imagines the effect of the killings on the families and loved ones left behind: on the child who will never rush into his father's arms, on the housewife who will wait in vain for her husband, on the mother who will never clasp her son in her arms, on the beloved who will not see her lover again. He has not come to weep, the poet says, for those who gave their lives for their language, for their culture, for their poets and their poetry, but to celebrate them.

I have not come here to weep for them

who gave their lives under Ramna's sun-scorched krishnachura trees

for their language

those forty or more who laid down their lives

for Bangla, their mother tongue,

for the dignity of a country's great culture,

for the literary heritage of Alaol,

Rabindranath, Kaikobad, and Nazrul,

for keeping alive the bhatiali, baul,

kirtan and the ghazal,

those who laid down their lives

for Nazrul's unforgettable lines:

"The soil of my native land

Is purer than the purest gold."

Translated by Kabir Chowdhury

The dirge that accompanies the probhat feri, "Amar bhaier rokte rangano ekushey february ami ki bhulite pari" (Can I forget the twenty-first of February steeped in the blood of my brothers), is a song of remembrance and mourning. There is anger there too as well, but it is the iteration of the opening lines that accompany the barefoot procession on the day that people remember. By contrast, "I Have Not Come Where They Laid Down Their Lives" – the title given to the translation by Kabir Chowdhury -- is, from the very beginning, an angry poem, a poem of determination, even while being an elegy. At the same time, it is a poem that encapsulates what being Bangali means. It is almost epic in scope as it embraces the land and people of Bengal, the writers who have glorified its spirit. The complex of grief and anger, of celebration and remembrance make it unique.

In his essay "Twentyfirst February," in Essays on Ekushey: The Language Movement 1952 (1994), Khan Sarwar Murshid noted how the commemorations of Ekushey had become part of "a Government supported orthodoxy." The earlier fervour where individuals with small bunches of flowers in their hands walked slowly to pay their homage to the language martyrs has been replaced by political bands and institutional groups vying for position in front of the television cameras.

The fire that inspired Mahbub's poem seems to have died down where the Ekushey commemorations are concerned. The gate from which the procession emerged – now part of the Dhaka Medical College and Hospital – is lost behind makeshift shops and hordes of rickshaws. Only, if one looks up, can one see the plaque commemorating the event that took place there.

The killers of Rafiquddin, Jabbar, Barkat, Salam, Ohiullah and Shafiur Rahman were not punished. But, yes, Bangla became a state language along with Urdu. The events of 1952 have led to the recognition of the importance of mother tongues. On November 17, 1999, UNESCO adopted a resolution proclaiming February 21 International Mother Language Day. The day is no longer just Shaheed Dibosh, Language Martyrs' Day, but a day which recognizes the right of every individual to speak in his or her own language.

However, every time there is injustice, every time those in power order or allow the innocent to be killed, the spirit that inspired Mahbub Alam Chowdhury to write his poem flares again.

Niaz Zaman, Advisor, Department of English and Modern Languages, Independent University, Bangladesh, is a writer and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments