“Most of the commentators are unaware of the importance of the events between 1948 and 1952.”

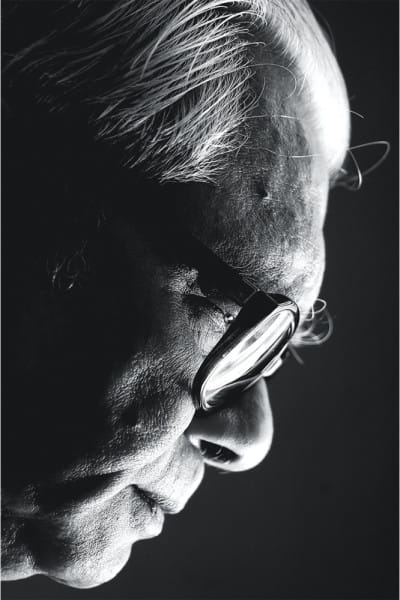

The Daily Star (TDS): What was your involvement in the Language Movement in 1952?

Badruddin Umar: As a general student, I participated in every public event of the Language Movement in 1952. On February 21, for example, I was present at the Amtala meeting where students debated whether or not to violate Section 144. Eventually, when they broke Section 144, I was in the procession. When police opened fire on the students, I was at 12-number shade which was adjacent to the Medical College gate. Barkat was also there. I saw him get struck by a bullet.

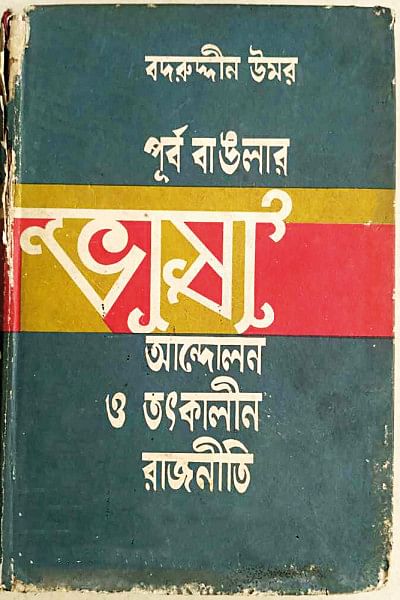

I was neither a leader nor an activist of the movement. I was only a close observer. It helped me a lot in writing my book on the Language Movement and cross-examining the information shared by various people involved with the movement whom I interviewed for my research.

TDS: What motivated you to undertake such an extensive research project on the Language Movement?

Badruddin Umar: In 1969, I undertook the plan to write a book on the Language Movement. Earlier, when I was a faculty at Rajshahi University, I wanted to write about the post-partition history of East Pakistan. However, since my family migrated to East Pakistan in 1950, I didn't have much information about the early years of East Pakistan, and I couldn't make much headway with the project back then.

When I started working on the Language Movement, I contacted Kamruddin Ahmad. He was a very learned and honest person. He was also closely involved with the political developments in this region for a long time. I was greatly benefitted from the multiple discussion sessions with Kamruddin Ahmad. He provided me a perspective on the socio-political development in East Pakistan since the partition.

TDS: You mentioned in your book that there is a big difference between the two phases (1948 and 1952) of the Language Movement. What's that difference?

Badruddin Umar: In 1948, people of Old Dhaka were very hostile to the student's demand for recognising Bangla as a state language. Students involved with the movement were even physically assaulted by them. But, in 1952, the same people actively supported and participated in the Language Movement. All the events of February 22 occurred in that area. I started to think about this shift in their attitude seriously. I tried to investigate the causes behind such a change.

Firstly, I found the unmindful repression by the Muslim League government. The government tried to suppress any kind of protest against the regime pre-emptively. They didn't do anything for the betterment of the common people. They indulged in reckless corruption, loot, and exploitation. Another major cause of resentment was the food crisis that had been plaguing the region since the partition. The food crisis disenchanted the peasants and general people with the ideal imagery of Pakistan.

I have extensively written about this crisis and the sufferings of peasants and labours in my book. Many people say that I added those things unnecessarily. They don't have any perspective of the movement. A movement like the Language Movement in 1952 cannot take place without a strong social basis for it. They want to portray it as a movement of students, teachers and intellectuals, and, according to them, the reason behind the movement was the killing of students by police firing.

Mao Tse Tung said that a single spark can start a prairie fire. In 1952, East Pakistan was on the verge of explosion. The firing incident was just a spark. Most of the commentators on the movement are unaware of the importance of the events that happened between 1948 and 1952.

TDS: Religious nationalism was a key force behind the creation of Pakistan. However, five years into Pakistan's existence, we see emergence of linguistic nationalism among Bengalis surrounding the question of state language. How did that shift happen?

Badruddin Umar: During the colonial period, there were several contradictions, including communalism, colonialism, regional disparities, and language. However, two contradictions came to the forefront: colonialism and communalism. The former paved the way for the independence of British India, while the latter caused the eventual division of the country.

With the partition of India along communal line and migration of a large number of people belonging to Hindu community, the earlier basis of communalism ceased to exist in Pakistan. New conflicts over language, race, and regional disparity emerged. These contradictions started to develop since the early days of Pakistan and reached a climax in 1952. Many say that the 1952 Language Movement paved the way for 1971. I don't agree with them. The development of the contradictions over the course from 1947 to 1971 is what led to the eventual emergence of Bangladesh. The 1952 Language Movement is but a dot on the road to independence.

Communists failed to identify these contradictions properly. They failed to differentiate between "national development" and "nationalism". The former is about the development of education, culture, living standard and so on while the latter is always aggressive. Nationalism is closely related to fascism. Therefore, the progressive left movement collapsed in the 1960s. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman filled this gap and brought a nationalist programme of politics at the forefront.

TDS: What did you mean by "return of the Bengali Muslim to their homeland" in your book?

Badruddin Umar: A section of Muslims in this country used to hold a belief that Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, etc were their actual homeland. With the development of national consciousness, they started owning the Bangla language as their mother tongue and the country as their homeland.

TDS: What was the impact of the 1952 Language Movement on the future course of politics in East Pakistan?

Badruddin Umar: I don't think it is the right approach to look at the 1952 Language Movement as a separate event. Rather, it was a part of the continuous development of contradictions which started in 1947 and reached a peak in 1971. However, you can say that the Language Movement put a huge impetus behind the development of these contradictions.

TDS: Although Bangla is now the state language of Bangladesh, it is still neglected. What is your opinion?

Badruddin Umar: In reality, Bangla is not respected as the state language in Bangladesh. English dominates the scene. The upper class sends their children to English medium schools. They shed crocodile tears for Bangla on February 21. They are hypocrites. Their children can't even read Bangla. They have no knowledge about the great literary tradition of Bangla.

I was reading an article in The Daily Star recently which revealed the extremely poor condition of research in this country. Allocation for research is insignificant, with less than 100 crores allocated for the research. Most worryingly, they are even unable to spend this miniscule budget.

Thousands of students graduate from schools and colleges every year, but they don't know anything beyond their textbooks. If you look at the literary scene, there have been no notable figures in recent years. All the major poets were the product of the sixties. So, what happened after 1971 in literature, culture, and research in this country? When literature, culture and research have seen no development, how do you expect the development of the Bangla language?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments