Killing grounds left uncared for

Tension between Bangalees and Biharis (Urdu speaking people) was soaring since the historic March 7 speech of Bangabandhu in 1971. There were clashes at places, including in Dinajpur and Rangpur, the strongholds of the Biharis who favoured a united Pakistan.

Days before the Operation Searchlight, when the Pakistani forces killed hundreds of innocent people in Dhaka, the conflict had spread to the Bihari stronghold of Kalapani, now called Shaheedbagh in Mirpur.

There were only 26 Bangalee families in Kalapani surrounded by the Biharis. The Bangalee families fearing for their lives started fleeing Kalapani and taking shelters in relatives' homes since the middle of March.

Shahjahan, then a resident of Kalapani, his mother, two elder brothers, sister-in-law and two children fled on March 23. They first went to his uncle's home in Nilkhet but after March 25, they moved to Aricha.

Shahjahan left behind his father Sheikh Abdul Malek, 96, and brother Abdul Gani, 9, considering their age. Some Bihari families close to them protected the two for a while but eventually they had to give in to the overwhelming number of pro-Pakistan Biharis.

"The Biharis tied my young brother and father together, beat them up and set them on fire," said businessman Shahjahan, recalling the brutality of the Biharis on March 25.

On that very day, the Biharis had killed six of a family, including a day-old child, and dumped the bodies into a ditch close to what is now ECB Chattar on the Mirpur-12-Airport Road.

"Nearly 150 Bangalees were picked up from various places in Mirpur, brutally killed and dumped into that ditch," said Abdur Rahman, 56, of Kalapani, who witnessed recovery of skeletons of those killed.

The skeletons were buried at the Martyred Intellectuals' Graveyard in Mirpur in 1973, and now there is no trace of the dumping ground and none of this generation know about it.

"I lost my father and brother. We know the killing spot, but nothing is there to mark the spot. It is so painful," said Shahjahan.

Many such killing fields and mass graves have been left unprotected and unrecognised and unmarked for more than 43 years.

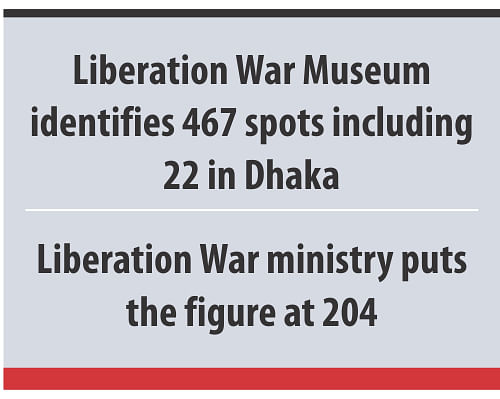

According to the Liberation War Museum, there are 467 killing fields and mass graves across the country, and 22 are in Dhaka city alone. Kalapani was not even on the list.

The liberation war affairs ministry, however, has only record of 204 such places. There was no record of Kalapani there either.

The Daily Star correspondent visited 25 killing fields and mass graves in Dhaka city and found no mark or sign in at least 15. The memories of those who witnessed the killings, however, were still fresh.

In Alobdi of Mirpur, there were five wells that were filled with bodies during the war. At a low-lying paddy field there a few thousand Bangalees were killed, according to Ali Akbar, 54, a resident of Alobdi.

"I was forced to dump the body of my cousin into a well just after the Biharis and the Pakistan army killed him," said Akbar, a lucky survivor.

Alobdi is also not in the records of the government, even though a war crimes tribunal convicted Jamaat leader Quader Mollah for taking part in the killing of 344 people there.

Rustam Ali Mollah, a witness of the Mohammadpur Physical Training Institute torture cell, said, "Around 1,500 people, including intellectuals, lawyers, and doctors, had been tortured and killed there and many women were raped."

In 1971, he was working with freedom fighters as an informant.

There were two other torture cells in the city, on Road-112 in West Nakhalpara and one at Dhanmondi Government Boys High School.

"Razakars and the Pakistan army used a then one-and-half-storey house at West Nakhalpara as a torture cell. Many Bangalees, including Rumi, son of Shaheed Janani Jahanara Imam and Altaf Mahmud, lyricist of Amaar bhaiyer rokte rangano ekushe February, were tortured there, said freedom fighter Jahir Uddin Jalal, who also faced torture but managed to escape.

"When I was taken to the torture cell I saw all the fingers of the right hand of Altaf Mahmud cut off, the eyes of Rumi was damaged and his right leg and back were broken. Other freedom fighter were in similar condition," he said.

Md Alauddin Kazi, a cleaner of the Dhanmondi school in 1971, said the Pakistan army would bring in Bangalees from places and then take them somewhere else. "I often found blood stains in a room while cleaning," he said.

There is also no mark at the killing field where the Institute of Mental Health and Hospital now stands at Sher-e-Bangla Nagar. The staff quarters of the Agricultural Training Institute used to be there.

Abu Taher, former driver of the training institute, told The Daily Star that he had seen bodies, with their hands, legs tied and blindfolded, dumped inside the boundaries of two staff quarters. One of the 10 bodies had an EPR Comilla uniform, he added.

In Sayedabad, there were 14 jheels between Koratitola (now Sayedabad bus stop) and Dholpur. Bodies of Bangalees were dumped in most of the waterbodies, said Mohammad Solim Uddin, a freedom fighter and a resident of Dholpur. There is no mark, sign, monument or memorial there.

The killing field at Shiyalbari in Mirpur is also unmarked.

"After the Liberation War, I along with many others found piles of several hundred skeletons at a family graveyard in Shiyalbari near Road-6 and a well between Road-6 and Road-7 in Shiyalbari almost full with bodies," said Md Abul Hossain, 65, who had escaped the Biharis' onslaught.

Mofidul Haque, trustee of Liberation War Museum, said a social initiative was necessary to protect these places and to preserve the memories of martyrs for the next generation.

He said it could be done through small and innovative ways.

Liberation War Affairs Secretary MA Hannan said they had sent a project proposal, to cost Tk 250 crore, for protecting the killing fields and mass graves across the country. The proposal was with the planning commission and they would start work after getting the approval of Ecnec.

The Thataribazar killing field, Bosila Etakhola (now Kaderabad housing in Mohammadpur), Shirnirtek killing field, Lohar Bridge killing field at Gabtali (beside Amin Bazar bridge), several mass graves in Mohammadpur, the killing field in Rokeya Hall of Dhaka University, the mass grave in Adabor and the killing field in Sharengbari in Mirpur have no mark or sign of identification.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments