Expansion of ACC’s power

ANTI-CORRUPTION Commission (ACC) can now arrest civil servants without permission from the government under the draft of Sorkari Kormochari Ain. The ministerial cabinet has come off from its previous stance, which in 12 July 2015 had proposed of a draft provision that required prior approval from the government before such an arrest could be made, spewing a lot of criticism. Law minister Mr. Anisul Huq remarks that 'after the changes, there is now no reason to question why civil servants are being exempted from ACC laws'. (Daily Prothom-Alo, 7 September 2016).

The previous provisions were created keeping in mind to avert harassment of civil servants while they are undertaking their duties and obligations. In conjunction with administrative reforms and a permanent pay scale commission, the prior law had also set out a provision for the arrest of public servants: if a government official is to be arrested for a criminal conduct while at his official capacity, the arrest has to be first approved by the court. However, once the charge sheet is accepted by the court, no such bar for detaining the individual would be present.

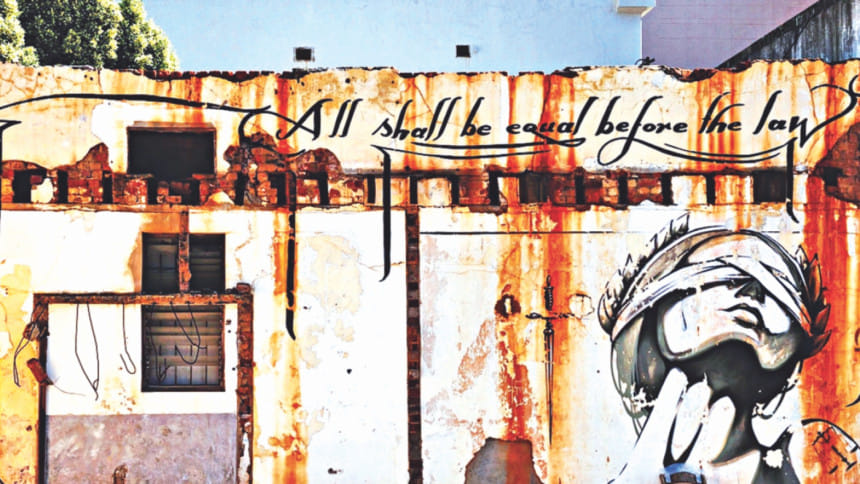

The draft bill sparked outcries from organisations such as Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), who referred the proposed law as repugnant to the constitutional right of 'Equal treatment before the eyes of the law'. Subsequently, this law would only promote corruption and encourage officials to abuse their vested powers, many said. Eminent lawyer Dr. Shahdeen Malik, had expressed his share of concern over the reform. In his eyes such provision would be retrospective, much like the medieval times, when officials could not be held accountable for misdeeds. He had added that if implemented, such arrangement would contravene the concept of democracy and serve to disrupt social balance. The then ACC chairperson Mr. Mohammad Bodiujjaman contented that ACC law will preside over any other law. Contrastingly, the Bill in question also proposed itself to be prioritised over any other existing laws.

Article 27 of the Constitution of Bangladesh deals with the notions of equality before law and equal protection of law. Nevertheless, the new provision aims to create a special entitlement for civil servants, thus creating social disparity and constitutional segregation.

In a prior instance, a similar provision safeguarding civil servants was passed in the Parliament in 2013. According to the Anti Corruption Commission (Amendment) Act 2013, for a corruption case to be put forward against a civil servant, it had to be priorly approved by the government. In State v Human Rights and Peace for Bangladesh (HRPB) (2013) the High Court Division of Bangladesh declared the law to be in direct conflict with constitutional arrangement. The judgment of the case stated that such a reform of the law would create a division between the masses and the corrupted, only to serve as a shield for the latter. But even after a precedent being set by the Court in a similar issue, the draft went on to be approved by the ministerial cabinet.

The Delhi High Court has restored the powers of Delhi Government's Anti Corruption Branch to probe and prosecute all government corrupt employees, within the jurisdiction of Delhi. The verdict, though a direct embarrassment for the Central Government, was a decisive victory for the people of the national capital. In the USA, a few months back, an Oklahoma lawmaker had proposed a bill, which aimed to exempt lawmakers from prosecution of nearly any crime that is normally handled by the local level. The power for prosecuting State officials was suggested to be granted exclusively to the State's Attorney General. The suggestion was met with vehement criticism; the District Attorney expressed concerns that the bill would create a different class of citizens disrupting the due process of law.

In pursuance of greater accountability and transparency, the changes made in the law are simply laudable. As noted above, both domestic and common law precedents point to the unfairness of safeguarding civil servants, as an unconstitutional or perhaps even immoral act of superseding people mandated powers. There is no doubt that the prior position would have been in direct conflict with the fundamental pillar of rule of law and prosecution of an individual should be decided by the gravity of actions, definitely not by his identity or position.

The writer is a student of law, University of London International Programmes.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments