MAKING BANGLADESH AN ATTRACTIVE FDI DESTINATION : Challenges and options

FDIs have two competing interests: economic development for host states and profit maximisation for foreign investors. It is the lure of maximum profits that persuade foreign investors to invest. The achievement of FDI-induced development requires appropriate balance between the two competing interests in any FDI regulatory regime in host states. FDIs are exposed to commercial and non-commercial risks. Foreign investors minimise these risks by investing where profit earnings commensurate with the risk posed. They resort to hedging techniques to control commercial risks, but non-commercial risks are beyond their control. It is this non-commercial risk where Bangladesh can improve significantly. Balanced regulation for development and protection for FDIs can create a win-win situation for the parties. Improvements and reforms in internal FDI climate to reducenon-commercial risk may be more palatable than regulatory relaxation to present Bangladesh as an attractive FDI destination.

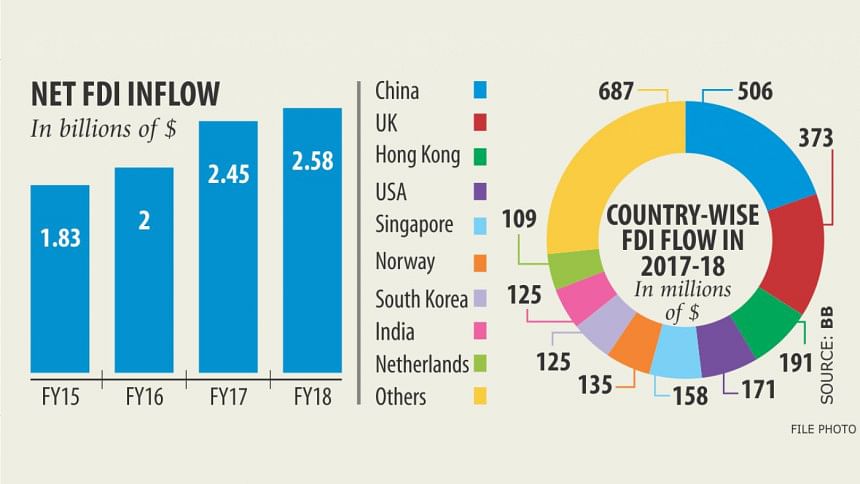

The US State Department Investment Climate Statements 2018 on Bangladesh has listed some internal impediments to FDI inflows reducing the rate to only 1% of GDP, one of the lowest of rates in Asia. The main barriers listed below are well-known and continuing.

♦ Inadequate utility and infrastructure services for cost-efficient transportation through functional ports, deep sea port, and railways facilities;

♦ Insufficient utility services, electricity, gas, and water supplies;

♦ Poor and fragile technology-based trade facilitation at the customs/ports deterring speedy market access and questionable effectiveness of FDI-related online services;

♦ Safeguarding workers' rights to association and collective bargain remain unaddressed;

♦ Weak law, order, and enforcement raise security concerns among foreigners;

♦ Lacklustre intellectual property rights protection and counterfeit goods prevention and a draft Patent Act 2014 remains under the Ministry of Industries for review ever since;

♦ Bureaucratic delays, red-tapes, and corruption remain continuing problem;

♦ Lack of judicial independence free from executive interference and corruption in lower courts. Bangladesh scored 2.38/7 in the World Bank 2016 Judicial Independence Index;

♦ Slow adoption of ADR mechanisms and slow courts impede FDI disputes resolution;

♦ Underdeveloped capital markets, high dependence of the financial sector on banks, and limited financial instruments amid the risky and unstable banking sector.

Addressing these domestic barriers would go a long way to improve a favourable FDI climate in Bangladesh. The Foreign Private Investment Act 1980 (FPIA) and the National Industrial Policy 2010 (NIP) may be amended to articulate the methods and forums of FDI dispute settlement. Effective local judicial remedies may be provided by establishing specialised courts or chambers in existing courts with judicial capacity for speedy FDI dispute settlement. Foreign investors are gradually turning to the Bangladesh International Arbitration Centre for FDI dispute resolution. This welcoming trend must be capitalised by improving further its functional competence to be a more reliable non-governmental commercial arbitration forum. The US State Department Statements recognise the open policies and generous incentives available under the FDI laws and policies of Bangladesh, which are not the actual barriers to inbound FDI flow. Bangladesh provides enough fiscal and non-fiscal incentives to attract FDIs and further incentivised regulatory relaxation would not be a panacea to attract more FDI inflows. Rather it must deal with its internal barriers that scare and turn away foreign investors.

Positive contribution to its development is the primary goal of Bangladesh to invite FDIs. Increased FDI inflows do not automatically translate to development, whose achievement requires appropriate regulation. Regulatory relaxation as incentives for inbound FDIs calls for scrutiny suggested below to see whether they advance or hinder development in Bangladesh.

Entry screening

Introduce minimum entry regulation to replace the current paperwork-based approval procedures. Specific sectors for FDIs and requirements relating to inflows of capital and foreign exchange, local content, employment, and technology transfer may be made publicly and readily available. Local equity participation may further be encouraged in joint ventures to control partial equity ownership. The full foreign ownership may be revisited to make it conditional, such as training for human capital development and handover some heavy machinery after the completion of FDI projects. Malaysia requires export of 80% of products and not to compete with locally manufactured products in local markets in approving 100% foreign equity participation. The screening, reviewing, and approving role of the Bangladesh Investment Board should proactively assess the developmental aspects of inbound FDI proposals backed by subsequent performance and compliance monitoring.

National interest

Inbound FDIs must pass the national interests test, which should include the net economic benefit and policy compliance. A screening and approval manual with a list of criteria along the line of the regulatory directives in section 3 of FPIA to avoid arbitrary and non-transparent decision-making should be made readily available to prospective investors and used to determine net economic benefits and policy conformity. The net economic benefit must assess whether the proposed FDI would (a) inject new capital or borrow capital from banks in Bangladesh under FDI concessionary loans; (b) bring new technology and transfer to the local economy; (c) contribute to new employment opportunities and local capacity-building; (d) generate new revenue-earnings; (e) promote trade in local raw materials and exports; and (f) repatriate full or part FDI earnings and/or reinvest in Bangladesh. National laws and policies conformity should require FDI proposals to be compliant with the Constitution and its state policies, and laws and policies on the environment, occupational health and safety, taxation, labour, security, defence, heritage, and natural resource exploitation.

Reasoned incentives

Incentives to attract FDIs must be subject to a cost-benefit analysis to prevent revenue losses and capital control risks. Tax holidays are a major cause of consecutive revenue losses due to their abuses by foreign investors taking advantage of long duration, lack of effective control, and administrative corruption. Various direct and indirect tax incentives lead to huge tax expenditure often outweighing the expected revenue. A tax incentive and expenditure review and monitoring mechanism to produce periodic reports for public scrutiny in parliament is necessary. The existing equal facility for low interest rate bank loans provides an opportunity for foreign investors to invest by borrowing substantially from local banks with very little or no capital transfer, which hamstrings the growth of local small and medium enterprises. Strict requirement of guarantees for the realisation of non-performing loans must be introduced. Export incentives must impose restrictions on importing foreign raw materials. The repatriation of FDI earnings with no limit or waiting period for remittance (EPIA, section 8) may be revisited to require partial reinvestment or full repatriation only after the payment of corporate income tax and the fulfilment of all other dues and financial obligations.

FDIs entail positive and negative impacts for host states, which must take measures to turn positives outweighing negatives. A strict regulatory FDI regime in Bangladesh must be in place to ensure FDI-induced development that should go hand-in-hand with adequate protection to investors. Only those FDIs that support development deserve to be invited and protected. Regulatory restraint on FDIs inimical to its national interest is in order and imperative to maximise development. Currently 8 public and 1 private (owned by Koreans) Export Processing Zones (EPZs) are operational and Bangladesh has announced to create up to 100 new privately-owned Economic Zones (EZs) and invited private investors, foreign and local, to develop these EZs. It is high time for Bangladesh to get its FDI laws and policies together. Concentrating on addressing and reforming its internal barriers more than further regulatory relaxation is likely to be rewarding in making Bangladesh an attractive FDI destination.

The writer is Professor of Law and Director, Higher Degree Research, Macquarie Law School, Macquarie University, Australia.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments