In search for a universal rule: Rule of law, democracy, and human rights

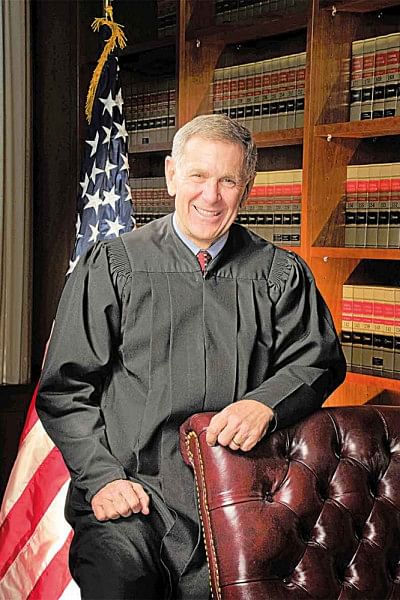

David Ormon Carter is a Judge of the United States District Court for the Central District of California. David began his legal career as an Assistant District Attorney with the Orange County District Attorney's Office in 1972 where he became the senior deputy district attorney. Since 1994, he has been the Visiting Professor to teach The International Law of Narcotics Trafficking and Terrorism at the Political Science Department, University of California Irvine. Some of the notable cases where he was the adjudicator include Mexican Mafia trials of 2001 (United States v Fernandez), Aryan Brotherhood trials of 2006 (United States v Mills), Armenian Mafia trials of 2012 (United States v Arman Sharopetrosian), and international terrorism cases such as United States v Leung (2005), United States v Afshari et al (2009), etc. He is now associated with Federal Judicial Center, Orange County Federal Bar Association, Federal Judges' Association, and many other institutions. Mohammad Golam Sarwar, Consultant, Law Desk, The Daily Star talks to him on the following issues.

Law Desk (LD): How do you view the current condition of the rule of law and democracy globally?

David Carter (DC): Hillary Clinton, while being the Secretary of State of the United States of America, posed a wonderful question about what the rule of law is, and I think we are searching for a universal rule that is somewhat achievable, though not uniformly, across the world. An example may be how one defines terrorism. The USA has struggled with the definition which, according to it, is now an act or a failure to act that influences governments and where there is a horrendous crime involved in an effort to change our government. However, in giving that definition it understood that individual countries would be able to modify that definition. So, for me, the rule of law rests on the concept of fairness and I am concerned - whether it be in relation to terrorism, or environment, or human trafficking – that we are tackling the problem in a way that puts us in a position of conducting improper trials. When we do that, we become a society that inflicts punishment without a proper trial and our aim should be to ensure proper trial and safeguards. If we do that, we become the alternative to the terrorist system. If we rush to quick and improper solutions, I would be concerned about the rule of law and this would also cause problems with sentencing and punishment. We need to be thinking about whether we can tackle these issues with lesser punishment or an increased focus on rehabilitation – the example of rehabilitation and reintegration of Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka may be noted in this regard. Whatever definition we may have of the rule of law, it has to balance punishment, deterrence and human rights. And this has to be the judiciary who has to seek that balance.

LD: Why have we failed to utilise the framework of human rights in tackling the pandemic?

DC: Balancing the interests of economy and the public health at a time like the COVID pandemic is a thorny challenge – there is no absolutism. This will naturally take jobs and largely so, from the poor. There are studies that state that minority populations in the US are less likely to take the vaccines as they are historically subjected to poor medical treatment and therefore are less likely to trust the government. Therefore, making vaccination mandatory, particularly in places of work, raises a question of whether we have built a healthcare structure where this would be viable. The pandemic has permanently changed the workforce and poorer communities are mostly harmed by it.

The mass media plays an important role in the society as the government alone cannot educate or motivate the population into voluntarily complying with health and vaccination measures. Democracy right now is being tested – for a while the world order was leaning towards increased democracy; but in recent times, there have been doubts about whether democracy is the most effective way to tackle some of the contemporary world issues. Democracy can be slow process – rendering good but not perfect outcomes. But when democracy wanes or subsides, we may get quicker solutions, which may not take into account the general interest of the population of the country. When people are empowered so as to participate in decision-making, they are more protective of the society and its interests. But when their voices are taken away, for example, by lack of access to courts or judicial processes, they may resort to self-help or violent tactics. Not having a speedy and effective trial seriously hampers human rights as the accused is kept in custody for long periods of time even before conviction. We must come up with a mechanism giving the judges more discretion to reach resolution in cases in a more speedy and efficient manner. Judges and academics should have more avenues to make inputs into the legislative mechanisms in order to achieve this.

LD: How do you assess the role of the international community to address the issue of displaced people from Myanmar and the environmental, economic, and security impacts of the influx on Bangladesh?

DC: We must evaluate why the international community is more attentive to the issue of Ukraine when compared to the issue of Rohingya displacement from Myanmar. It could be out of self-interest or could be that the international community is not fully cognisant of the inhumane treatment the Rohingya people underwent, perhaps due to cultural, ethnic or religious differences. Culturally, Bangladesh is more sympathetic to the Rohingyas due, among others, to the common religion. Humanity gets lost sometimes due to diversity and while it is commendable that Bangladesh is concerned about the plight of the Rohingya but we must also be concerned why the international community is not as responsive. The international community should have come to the aid of the Rohingya a long time ago. A country has to properly regulate the influx of people into its country to ensure that no one is abusing the processes and to screen out possible cases of trafficking. Bangladesh has, overall, tackled the issue in a very humane manner. Interrelationship between other countries and Bangladesh is of critical importance in order for them to be sensitised to the current situation in Bangladesh with regard to the Rohingyas.

LD: Thank you for your time.

DC: Thanks very much.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments