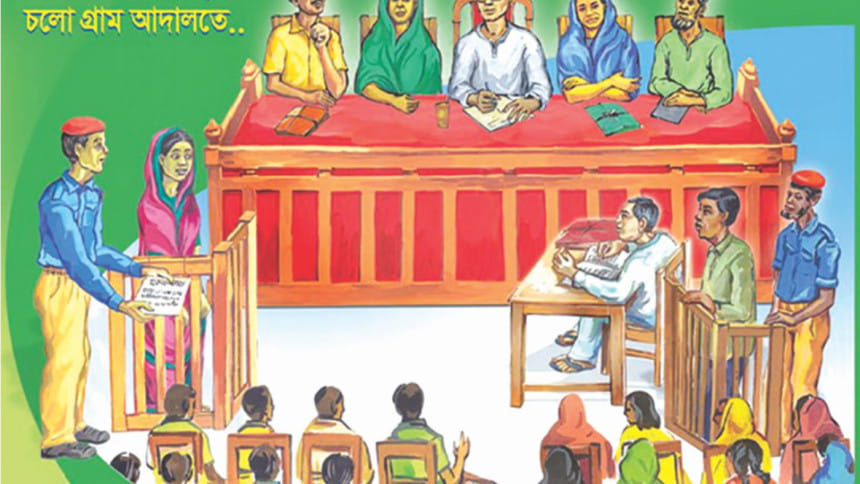

To make village courts effective

In rural Bangladesh, conflict management has been apparent over the years. The Village Courts Act of 2006, which replaced and updated the Village Courts Act of 1976, provides for the establishment of a court in every Union Council. Village Courts are comprised of a panel of five: the Union Council's chairman; two other Union Council members, one of whom is chosen by each party in the dispute; and then two additional citizens, who are also chosen by the parties respectively. The Courts have jurisdiction over civil disputes valued up to BDT 75,000. They also have jurisdiction over some crimes, including assault and theft, though they do not have the power to fine or imprison; rather they can grant simple injunctions and award compensation up to BDT 75,000. Administratively, the nodal department in charge of Union Councils is the Local Government Division (LGD) within the Ministry of Rural Development and Local Government. Village Courts and Arbitration Councils are also under the supervision of LGD, rather than of the Ministry of Law, Justice, and Parliamentary Affairs. This placement reflects the distinctiveness of the Village Courts and Arbitration Councils from the rest of the judicial system as Village Courts and Arbitration Councils are more local and less legal.

Village Courts are largely defunct and Union Council members have little knowledge of the Village Courts Act. The conflict-management system in Bangladesh is still inefficient, often favouring those parties with better financial means or with close contact to institutions. Poor and marginalised groups are clearly disadvantaged. Nepotism and corruption hinder smooth conflict resolution processes. Traditional conflict management and resolution procedures (mediation of elite villagers, shalish) and the intervention of Union Council seem to work well for small-scale conflicts. Nevertheless, their efficiency is severely limited in most land ownership-related conflicts.

Meanwhile, development partners (UNDP and EU) extending their technical support to the Ministry of Local Government Division for transformation of the local justice system on the basis of equity and inclusion within the context of broader local governance reform in Bangladesh. Village Courts can help to bridge between Bangladesh's informal and formal justice institutions in providing a fair arbitration process leading to delivering justice and human security. With a view to enhancing the fairness of Village Courts, policy makers can deem limiting the authority of the Union Council chairman, inclusion of refusal rules, requirements of public announcement of the sessions, and the right of parties to exclude a panelist. Insisting that Village Courts apply the general body of substantive formal law may be unworkable and imprudent. But fairness may be served by specifying a core set of fundamental rights with which Village Court decisions would be required to comply.

The writer is an Assistant Professor, Department of Government and Politics, Jahangirnagar University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments