Bangladesh should withdraw its reservation on the UN Genocide Convention

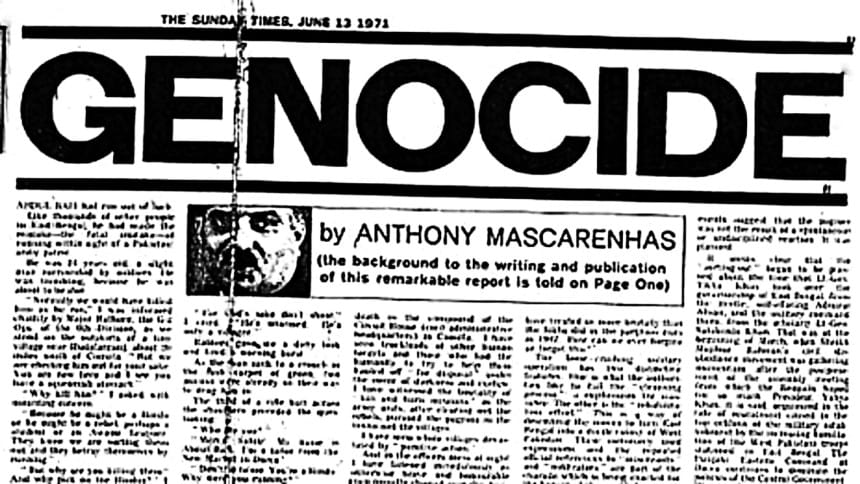

Bangladesh's independence is among the few examples of successful remedial secessions in the narratives of state succession. In essence, the doctrine of remedial secession implies the right of a group of people to secede from a mother state by exercising external self-determination outside colonial dominion following the commission of gross violations of human rights against them by the said state. Bangladesh's Proclamation of Independence 1971 highlights the Pakistani authorities' continuous commission of "numerous acts of genocide and unprecedented tortures, amongst others on the civilian and unarmed people of Bangladesh" as one of the grounds for asserting the independence.

In the aftermath of its independence, Bangladesh also made exceptional struggles to uphold justice for the victims of atrocities perpetrated against its population during the liberation war. The promulgation of International Crimes (Tribunals) Act 1973 exemplifies one part of such endeavours. However, Bangladesh's silence regarding the use of the Genocide Convention 1948 to strengthen its accountability efforts is contrary to its historical experiences.

Pakistan ratified the Convention on 12 October 1957 without any reservation. It signifies that the people of Bangladesh were under the protection of the Convention throughout the course of the liberation war. Even the obligation to prevent and prosecute the crime of genocide was considered as obligation erga omnes at that time (see Barcelona Traction case, 1970). In 1973, Pakistan commenced a proceeding against India at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) under the Convention in regarding the Indian proposal to hand over Pakistani prisoners of war to Bangladesh. In this period, Bangladesh's resort to the Convention could advance its accountability mission. Finally, it acceded to the Convention on 5 October 1998, but with a reservation on Article IX thereof.

Article IX of the Convention confers jurisdiction on the ICJ to deal with disputes relating to its interpretation, application, or fulfilment of the said Convention. This provision confronted significant opposition from the USSR and its allies during the negotiation of the Convention and even attracted significant reservations upon its adoption. It eventually led to the question of the legality of such reservations. The international community was divided into two camps, one favouring the integrity of the treaty regime (the prevalent practice of the League of Nations) and the other supporting the universality of the treaty regime. Finally, the ICJ's Advisory Opinion on the Reservation to the Genocide Convention (1951) resolved the issue stating that such reservations are valid as long as they are not incompatible with the object and purpose of the Convention. Afterwards, Article 19(c) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969 incorporated such dictum in the positive international law.

Bangladesh's reservation to Article IX qualified the jurisdiction of the ICJ. It states that "[f]or the submission of any dispute in terms of this [A]rticle to the jurisdiction of the [ICJ], the consent of all parties to the dispute will be required in each case." The language of the reservation is in verbatim adoption of that of India made on 27 August 1959. Apart from barring any disputant state from making any claims against Bangladesh at the ICJ, this reservation equally, due to the principle of reciprocity, incapacitates Bangladesh to sue any state, even though the latter has no reservation on Article IX. Myanmar highlighted this issue during the provisional measures hearing of the Rohingya Genocide case in December 2019.

The reservation in question runs contrary to Bangladesh's moral and legal commitments. As mentioned earlier, Bangladeshi people suffered serious human rights violations including the crime of genocide during its emancipation. While Bangladesh could not prosecute any Pakistanis for their roles in the commission of genocide till date, the International Crimes Tribunal prosecuted several indictments of genocide. At this juncture, Bangladesh's reservation on the Convention is contrary to its struggle and promises to uphold justice for the crime of genocide committed against its people. It is morally incompatible to claim justice for a crime committed against its people while denying justice for the victims of similar crimes elsewhere.

Bangladesh's reservation is also contrary to its constitutional commitment. Article 47(3) of the Constitution of Bangladesh enumerates the special safeguard to the trial of international crimes including genocide before Bangladeshi courts. This provision illustrates Bangladesh's strong standing against the impunity of génocidaires. Notably, the 1973 Act does not have any limitation on its temporal jurisdiction. Thus, Article IX of the Convention does not make any extra obligation to Bangladesh. Rather, it reiterates its existing obligation to punish and prosecute the crime of genocide under its existing domestic law.

On the other hand, Article 25 of the Constitution reiterates Bangladesh's fundamental policy to "support oppressed peoples throughout the world waging a just struggle against imperialism, colonialism or racialism." Article IX of the Convention could serve as a potential vehicle to support the oppressed people throughout the world by applying the principle of obligation erga omnes partes. The doctrine of erga omnes partes obligates any state party to a multilateral treaty to invoke the responsibility of any treaty violations by any other states parties despite being uninjured by such violations. A recent example of the application of this doctrine is exemplified in the case filed by The Gambia against Myanmar before the ICJ, in relation to alleged crimes of genocide against the Rohingyas. Though Bangladesh is supposedly supporting The Gambia by providing funds to maintain the proceedings, the non-reservation on the Convention could enable Bangladesh to make a direct claim before the ICJ for Rohingyas that it is harbouring.

As we draw closer to Bangladesh's 50th victory anniversary, it is important to reflect on Bangladesh's commitments to peace and security throughout the world by ratifying notable human rights treaties, supporting peacekeeping missions, and harbouring one of the largest refugee populations of the world. It is high time Bangladesh reconsidered the withdrawal of the reservation on the Convention. Such withdrawal of reservation from the Convention will strengthen Bangladesh' commitment to human rights both for its citizens and for the oppressed people throughout the world.

The writer is lecturer (on study leave) at american international university-bangladesh and a student of international law at université catholique de louvain, belgium.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments