Our ‘Problematic’ Law Making Process

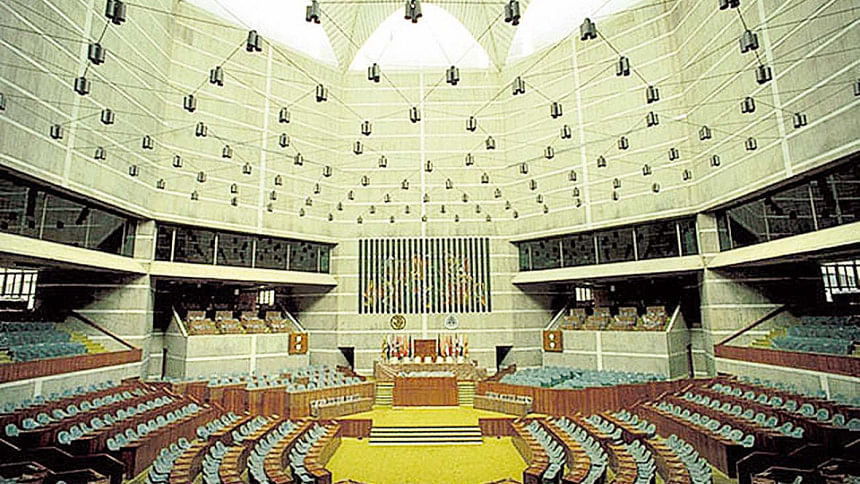

Legislative process in our parliament is claimed to be an upshot of the Westminster parliament. Like the Westminster, here government businesses are prioritised over private member initiatives for law making. However, unlike the Westminster, opposition and backbencher voices in Bangladesh are effectively muted to the advantage of the government’s aims to have its laws passed. Whereas the mother of parliaments itself has evolved extensively in favour of the members’ right to reasonable debate, ours is trailing miles behind both institutionally and procedurally. A comprehensive reading into the Rules of Procedure (RoP) of our parliament seems to suggest that MPs’ right to reasonable debate in the floor, committee and elsewhere is given a mere cosmetic gloss by severely restricting the scope of opposition to government bills and resolutions.

Unlike the British government, we don’t see any comprehensive legislative agenda from the government. Driven by a tendency of ad hoc-ism, most of the government’s legislative proposals reach the parliament as fait accompli which it simply approves. Scope of drafting exercise by individual members is very slim. The weekly private member business days are used up in MPs speaking out about local problems and success stories of the government than critiquing or legislating. Though we don’t have significant opposition in parliament now, oppositions in fifth, seventh and eight parliaments used most of the private member days in propagating the politically contentious issues rather than attempting to legislate and question the government’s policy preferences. Given the attitude, our history of private member legislation is demonstrably poor. Apart from the 13 Friday schedule for private member business, the House of Commons allows additional 20 days for opposition businesses and 35 more for backbencher debates. We have none of those but mass absenteeism from parliamentary duties.

Unlike the “Usual Channel” procedure of the House of Commons, there is no intra or extra parliamentary consultation with the opposition on how to time-table different stages of a bill’s consideration in the floor or committee. “Usual Channel” is a desk consultation between ruling party Chief Whip’s private secretary and opposition party whips on time-tabling the debate on a Bill. Compared to that, the all-party Business Advisory Committee (Rules 219-220 of RoP) of ours is subject to the hegemony of the Leader of the House. The Speaker has little to offer to the opposition and backbench expectations in scheduling a Bill’s parliamentary journey.

Once in the floor, a government bill usually goes to the committees. While members are expected to contribute substantially in the committee stage and the subsequent floor debate, we rather see routine abdication of meaningful debate there. The infamous Article 70 hunts the backbenchers in the floor. The passivity in the committee stage, however, is attributable to our deep-rooted culture of clientelist politics. Ruling party backbenchers are more likely to be proactive if they hold chairmanship or influence in the committee. That again won’t necessarily amend a governmental bill unless the committee is exceptionally lucky to be appreciated by the cabinet top notch. Amendments, if there be any, usually concern petty issues like date, punctuation and grammatical errors.

Opposition members on the other hand are handicapped in the floor and committee alike. As mentioned earlier, they don’t have any UK styled “Usual Channel” to negotiate a legislative time-table. Nor do they have any protection against government invoked immediate closure. Had those been permitted by the RoP, devices like guillotine motion (not immediate rather a time bound closure) or programming motion (fixing a strict time-limit for each stage of law making) could have offered some leverage for the opposition. Like the Speaker of the House of Commons, the Speaker of Bangladesh is vested with considerable power in allowing and ordering amendment proposals. Unfortunately, the demonstrable partisanship of successive Speakers contributed only in generalised suppression of opposition amendments.

Unless the committees take a genuine cross-party or non-party approach to a bill, which is very rare in fact, the opposition members’ scope to contribute in the committee stage also is limited to mere noting down of their dissent. Additionally, parliamentary committees’ power to take public evidence from representatives of special interest groups apart from the official oppositions is also rarely resorted to.

Parliament’s power over the purse of state is affected by tools like Votes on Accounts and Votes of Credit. Votes of Accounts are the advanced grants made by the parliament pending the final approval of a budget. A Vote of Credit is a privilege to withdraw from the consolidated fund for as long as sixty days in case a parliament dares to reject the government’s budget (Article 92(3) of the Constitution). At the expiry of the sixty days, government may simply adjourn the session and continue to withdraw money by promulgating a presidential ordinance (Article 93(3)). For the same parliamentary mode described above, ordinances once placed in the floor would simply be approved.

Travelling beyond the floor, the German Bundestag allows one-third of its members to challenge a highly controversial law before the constitutional court. We have judicial review and one instance of opposition MPs challenging a law (Abdus Samad Azad v Bangladesh 44 DLR 354). Unfortunately, this trend was not given a serious consideration by the later day oppositions. Again, the Swiss parliament members may call for a post-legislative popular referendum against a law by gathering around 50000 signatures within 90 days of its passing. While the Bangladeshi RoP allows a motion to circulate a Bill to solicit public opinion during its legislative phase (Rules 78-80, 282), this is routinely voted down in the floor.

Unlike the British House of Commons, we don’t have any post-legislative scrutiny of subordinate laws passed by the executive. That remains the sole privilege of the executive, i.e., the legislative drafting wing of the Ministry of Law. Despite all these, if we still find solace in calling ours a Westminster parliament, then yes – it is. But how could the doctrine of Westminster parliamentary system itself be blamed for the misery of ours?

The writer is Doctoral Researcher (Parliament Studies), King’s College London.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments