A preposterous directive on the apprentice lawyers

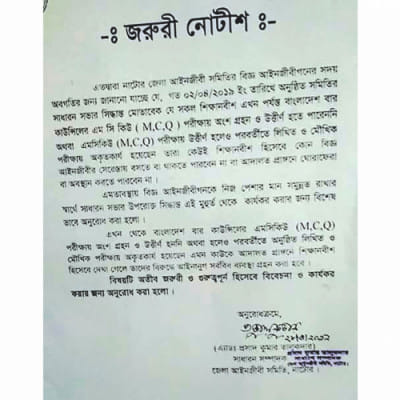

The directive appears to be misconceived from a legal point of view. While the Bangladesh Bar Council Canons of Professional Conduct and Etiquette (Canons) does not provide anything on the treatment of apprentice lawyers, Rule 10 of Chapter I states that “[j]unior and younger members should always be respectful to senior and older members. The latter are expected to be not only courteous but also helpful to their junior and younger brethren at the Bar”. While the Rule only spells out the duty to be helpful and courteous to the junior colleagues, i.e. enrolled lawyers, the message of mutual respect is unmistakably palpable. It may be argued that the same philosophy should apply to the apprentice lawyers and thus, it runs counter to the spirit of the Canons, if not its letters. By being in the court chamber of lawyers or roaming around the court premises as apprentice lawyers, the aspiring lawyers do not violate any law of the land. Thus, it would have been interesting if the directive specified under what legal authority and what kind of legal action the Bar Association envisages to take measures against any apprentice lawyer violating its dictate.

Indeed, it is dubious that the Bar Association even possesses the power to make any directive as to who would be roaming in the court premises as the court is a public place. The Association has a role in upholding the standard of the legal profession, not to decide who stays in the court premises as apprentice lawyers. The Bangladesh Legal Practitioners and Bar Council Rules, 1972 requires that before being admitted as an advocate, a person must take training regularly for a continuous period of six months as a pupil in the Chamber of an Advocate who has a practising experience of at least 10 years. Indeed, preparing notes on the cases on which an apprentice has assisted the senior lawyer is a part of the lawyer’s enrolment examination. So, it is not understandable when apprentice lawyers are prevented from sitting in the court chamber of lawyers or roam around the court premises as apprentice lawyers, how they can comply with these prerequisites for entering the legal profession. By this token, it would appear that the directive squarely contradicts the Bangladesh Legal Practitioners and Bar Council Rules, 1972 for which the office-bears of the Association should be legally answerable.

Beyond the question of the legal infirmity of the directive, its moral vapidity and undesirability are patent too. It shows an utter disrespect to the apprentice lawyers who would be junior colleagues in days to come. While an apprentice is not yet a lawyer, she/he is working to be one. There is a widespread perception held by many in the legal community in Bangladesh that many apprentice lawyers do not pay enough attention to the court practice. Observing the court proceeding as an apprentice lawyer is an integral part of the grooming of these would be lawyers and the Bar Association should have no business in preventing this. This is not just an issue of rights and dignity of the apprentice lawyers, but also an issue of not giving them enough space to hone their professional skill which may contribute to the deterioration of the standard of the profession.

To give the directive the benefit of the doubt, one may perceive it intended to prevent touts masquerading as apprentice lawyers cheating unsuspecting litigants which have sometimes been an issue. However, the unequivocal wording of the directive leaves little room to take this line of reasoning, as it targets ‘apprentice lawyers’. If touts are targeted, then they would have been targeted categorically. If for the sake of argument, we assume that the directive is actually not intended to target bona fide apprentice lawyers, then it is sad that the Bar Association has been so sloppy in conveying its message. It is high time that the leadership of Bangladesh Bar Council plays its role in dealing with this kind of a preposterous directive which does nothing to uphold the dignity of the bar and undermines the dignity of aspiring lawyers and also in turn, that of the legal profession.

The writer is an Associate Professor, Department of Law, North South University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments