On the disproportionate use of force on protests

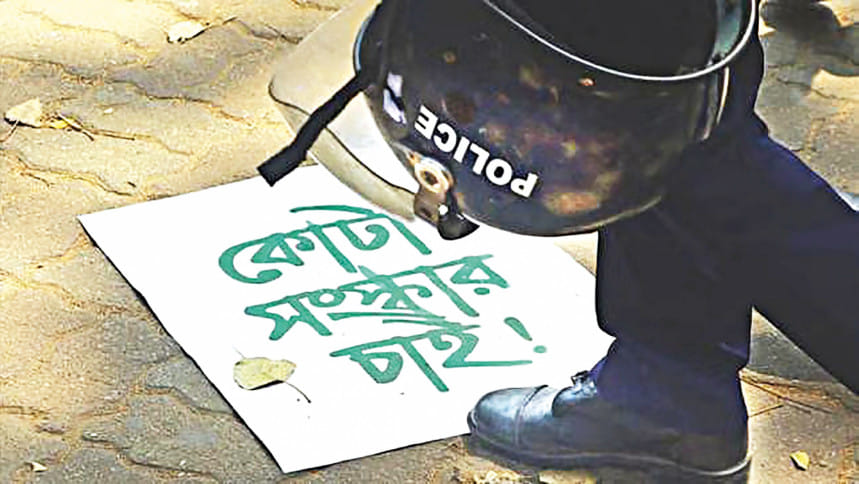

The reason we have law enforcement agencies in modern states is to protect the rights of the citizens. However, when disproportionate force is used against the citizens by states using these agencies, the very same rights are violated. Below is an analysis keeping the quota reform movement in the background.

Freedom of assembly and freedom of expression are fundamental rights as per our Constitution under articles 37 and 39, and also under our international obligations e.g., the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Restrictions may be imposed on such rights but they have to be reasonable, objective, and proportionate.

Especially when an unarmed or lightly armed person is killed, it is deemed to be disproportionate. Furthermore, it needs to be remembered that right of self-defence is not a right of the attacker but rather of the victim, which does not apply to the law enforcement agencies in most situations.

Under section 128 of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1898 (CrPC), the law enforcement agencies may disperse an assembly by force. However, the amount of force needs to be proportionate to the circumstance of each particular case (Queen-Empress v Subba Naik And Ors, 1898). Evidently, if a protester is shot (even with a rubber bullet) when he/she is keeping his/her arms open expressing anger towards the inhumane response of the law enforcement, it cannot be regarded as a proportionate response.

The law enforcement agency may argue that they are justified in using such force as self-defence. However, the fourth paragraph of section 99 of the Penal Code 1860 (PC) clearly emphasises the requirements of necessity and proportionality. Especially when an unarmed or lightly armed person is killed, it is deemed to be disproportionate (State of U.P. v Ram Swarup, 1974). Furthermore, it needs to be remembered that right of self-defence is not a right of the attacker but rather of the victim, which does not apply to the law enforcement agencies in most situations.

Additionally, police may use force to effect arrest of the protesters, which is allowed under section 46 of the CrPC. However, judicial interpretations of this provision again shows that the actions of the police need to comply with the requirements of necessity and proportionality (Dakhi Singh v State, 1955). Section 46(3) also prohibits the causing of death while using such force unless the person is accused of an offence punishable with death or imprisonment for life. It needs to be noted that the Police Regulations Bengal 1943 (PRB) in regulation no. 154, 155 mention similar requirements.

Next, coming to the question of criminal liability and legal defences, criminal charges under sections 302, 304, 323, 325, etc of the Penal Code can be brought against law enforcement officers for causing deaths and injuries to peaceful protesters. Section 132 of CrPC makes the job difficult as it restricts the option to initiate prosecution against such person without the sanction of the government. Even if prosecution is initiated against the responsible officers, the same provision mentions the 'good faith' and 'superior order' defences. As for the good faith defence, it requires due care and attention, and as for the 'superior order' defence, it cannot be pleaded when the order is manifestly illegal.

Moreover, the legal defences under sections 76 and 79 of the PC of 'believing in good faith to be bound by law' and 'believing in good faith to be justified by law' also do not apply when the law enforcement agencies could not have reasonably believed that they were obligated to or justified in using such disproportionate force that result in deaths (Jahir Mia and Islam Howlader v State 13 DLR 857).

But only putting all the blame on the subordinate police officers is unfair and ineffective. The superior police officers who enable and allow such acts can be held responsible as well as abettors. The legal defences for them should fail when the acts that cause large number of deaths and injuries are not the result of a mere mistake of fact in good faith but rather utter disregard to the principle of proportionality.

At times, attacks and use of force befall on protesters from non-state individuals or political activists. Needless to mention that there is absolutely no legal justification of such attacks when attackers are not part of the law enforcement force and have no authority to interfere with protests and assemblies. Furthermore, attacks, killings and human rights violations often also come as results of continuous dehumanisation, incitement to violence, and acts of abetment in the online sphere. Such acts clearly constitute offences under sections 25, 31, etc. of the (infamous) Cyber Security Act 2023 and other laws.

Lastly, in addition to criminal remedies, constitutional remedy is also available under Articles 44 and 102 of the Constitution. Indeed, for violation of Article 32 (fundamental right to life and liberty) the state has been asked to provide compensation in an array of cases.

The writer is the Law Desk Assistant of the Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments