Reservation, equality and non-discrimination

Of the affirmative actions taken by the state, reservation in public office is the most contentious one. The constitution of Bangladesh permits reservation for backward section of the citizens so as to ensure their adequate representation in the public service. Unless the interests of weaker are promoted, and until they are adequately represented, the idea of establishing an egalitarian society shall remain illusory. Therefore, the government provides reservation for backwards in public service.

Equality and non-discrimination are two touchstones upon which our constitution is founded. In the class ridden society of Bangladesh - where economic exploitation is historical, social and educational facilities are insufficient and disproportionately distributed - bringing the unequal into equality is the major challenge. The backwards - who have suffered socio-economic oppression –to avail fair share in public employment claim reservation. Whereas, another group defies reservation alleging that it amounts to economic oppression by negating equality in public employment. Therefore, the state is required to reconcile the tension between these contrasting claims.

The guarantee of equal opportunity in matters of public employment is a guarantee of something more than what is required by formal equality. It implies differential treatment of persons who are unequal. Egalitarian principle has therefore acknowledged that the government has an affirmative duty to eliminate inequalities and to provide opportunities for underprivileged. Proportional group equality is the concept of equality that permits reservation. The individual member of the group is granted preferential treatment if the group is underrepresented or systematically excluded from competing on an equal basis.

Equality does not imply absolute equality. The rule of differentiation is inherent in the concept of equality. Equal protection of law necessarily involves classification. However, validity of the classification must be adjusted with reference to the purpose of the law. If there is a rational classification consistent with the purpose for which such classification is made, equality is not violated. A classification, in order to be constitutional, must rest upon distinctions that are substantial and not mere illusory; it must have a reasonable basis. Article 29(3)(a) of our constitution, which permits classification requires a revisit to examine, whether the classification made so far is free from artificiality and arbitrariness, and whether the extent of the differential treatment is reasonable.

Merit and non-discrimination are universally recognised principles for public appointment. The merit principle requires that the candidate for public office must fulfill the prescribed eligibility criteria and merit alone should be considered for selection. The principle of non-discrimination requires that the best eligible candidate shall be appointed without any distinction or reservation.

Non-discrimination in appointment is a widely recognised principle, international covenants like article 21 (2) of the UDHR, article 25 of the ICCPR recognises equal access to public service without any distinction or restriction whatsoever. Apart from eligibility criteria any other consideration like race, sex, social origin etc., should be extraneous and discriminatory.

In performing duty, officials are influenced by their social backgrounds, values and ideologies. Therefore, fair representation in the public office helps to improve the quality of service. It also ensures a balanced composition so that all sections of the society do have representation and confidence in the administration. However, to ensure representation of different social groups appointments should not be made regardless of merit.

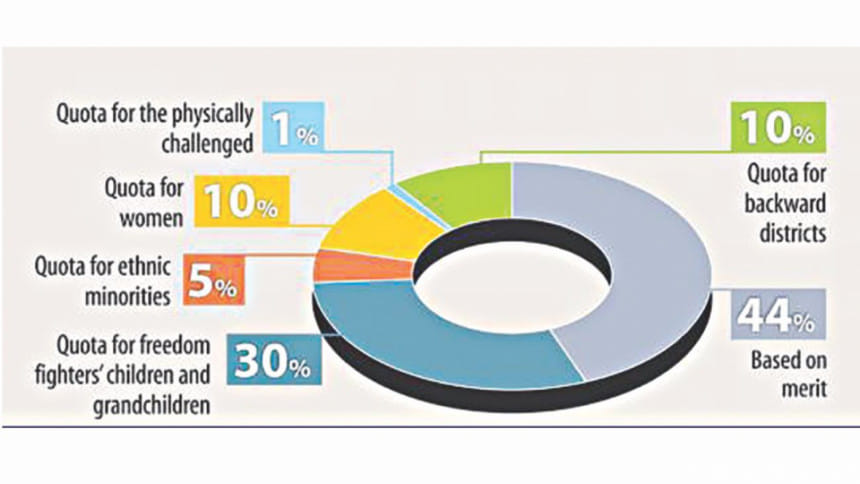

Presently, public officials are selected on the basis of 'merit' and 'quota'. From the list of successful candidates, 44% are selected solely on merit and remaining 56% are selected on the basis of quota. Of the quota posts, 30% are reserved for descendants of the freedom fighters, 10% for female, 10% for backward district territory, 5% for tribal and 1% for physically challenged people. Appointment in public office is seen to be dominated by quota not merit.

Reservation under article 29(3) (a) requires satisfaction of two conditions: firstly, the beneficiaries must constitute 'backward section 'and secondly, they are 'under-represented' in public service. However, the present reservation policy demonstrates that the requirements of article 29(3) (a) are not satisfied objectively. Again, creation of super privileged class for descendants of freedom fighters is beyond the constitutional scope and, a denial of equality and non-discrimination.

Article 29(3)(a) permits reservation on satisfaction of 'backwardness' and 'under-representation'; such requirements are analogous and concurrent. Mere 'backwardness' or mere 'under- representation' of any section of citizens does not justify reservation in their favor. Again, the 'backward section of citizens', despite having no illustration refers generally to the socially and educationally backward classes. In determining backwardness economic conditions, occupations and geographical location need to be considered. Reservation policy must accommodate these conditions to justify the protective measure.

There are underprivileged people within the perceived forward class of the society, who must have access to the state sponsored privileges. Similarly, there is a creamy class among the backwards who are to be excluded from the protective privilege. Social, educational and economic disparity and privileges simultaneously exist in every layer of the society. There are 'backwards 'among the 'non-backwards'; similarly, there is 'creamy class' among the 'backwards'. The creamy layer of the backward class is economically well-off, socially and educationally advanced. 'Equality of opportunity for unequal can only mean maximisation of inequality'. Therefore, the provision of reservation for the 'backwards' inclusive of 'creamy class 'would not be able to ease the persistent inequality the 'real backward class' is experiencing. Thus, it is the creamy class enjoying the advantage of reservation for the backward. It is not the 'unequal opportunity 'rather 'poverty' or 'resource constraint' impeding cherished mark of the backward. Consequently, even reservation for the 'backward 'may not alter the fate of 'more backward' as the 'creamy class' of the 'backward' outrace the 'real backward'.

Reservation necessarily involves appointment of less competent persons, which in turn leads to lowering efficiency of the administration. The qualifications, standard and talent necessary for backward section cannot be relaxed or reduced to a level which may materially affect the efficiency of the administration. Reservation must intend merely to give adequate representation to the backward; it cannot be used for creating monopolies or for unduly upsetting the legitimate interest of other contestants. A reasonable balance must be struck between reservation and fair competition as well as the requirement of administrative efficiency.

Equality and non-discrimination are core constitutional guarantee which the executive cannot overlook. Equal opportunity in public employment is the general rule and reservation is an exception. Exception should not overshadow the general rule. In advancing the backward, the government is not justified to ignore the remaining society. Only 44% merit based appointment is utter rejection of the constitutional commitment for equality and non-discrimination.

Article 29(3)(a) leaves an ample discretion for the state to provide many alternative privileges than mere reservation. Scheme may be taken to provide financial assistance, free medical care, educational and hostel facilities, scholarship, free transport and so on. Such privileges will also help the backward in attaining success through merit based competition. Reservation, if subsists, caution should be taken not to disappoint the deserving and qualified candidates. “An unfilled vacancy may not cause as much harm as a wrongly filled vacancy”.

The writer is Assistant Professor of Law, Jahangirnagar University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments