The fading sounds of ferriwallahs

People used to wake up to the sound of hawkers or ferriwallahs coming to sell eggs, chicken, and vegetables. I used to enjoy watching the morning crowd on the road through the balcony.

The day started with the sound of the rickshaw's bells, cars honking and above all, the calls from the hawkers. The number of cars were very few, and most of those were old models and some had dents which needed services at the garage.

This was the picture of '70s to early '80s Dhaka. The roads in the neighbourhood remained busy most of the day, except around 3 PM, for an hour or so, as the busyness in life used to slow down a little bit. Some rickety rickshaw pullers were taking naps on their rickshaws as business was slow. The tired hawkers were also taking a much-needed break under the shade of a tree to escape from the scorching heat in the late afternoon.

As a young girl, I was quite intrigued by the different echoing chants from the ferriwallahs. Each has a distinctive way of attracting customers to buy his merchandise. Ferriwallahs are door-to-door salesmen or mobile salesmen. They advertised their merchandise by loud cries on the street, or chants, and often made harmonious tones to attract attention. They were busy carrying their products around the various alleys of Dhaka. Mostly very slim figured, wore lungi, and had a gamcha, which they tied into the form of circle to rest the basket of merchandise on their heads. They were found walking bare-footed in the scorching heat or rain.

I can still visualise the scene of hawkers coming to our place or walking on the road chanting. The guy with the balloons was the popular one among children, and the smile he used to bring to us was priceless.

I often found some of the murgiwallahs, or chicken sellers very inconsiderate to their chicken as they used to hang them upside down, but some behaved humanely by putting the chickens in a big jhuri or basket and chanted "Murgi Lagbe, Murgiiiii."

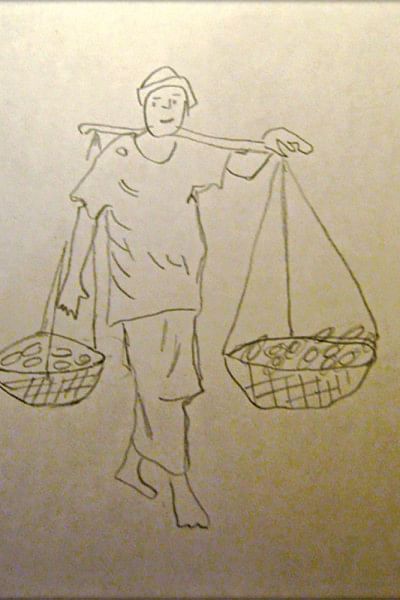

The pots and pans sellers were found chiming on the road after lunch-time, when the elders were relaxing and the house helps were busy cleaning and sweeping the kitchen after lunch. They were creative on putting pots and pans on the balance scale made of baskets tied to a bamboo strip and they used to hang it over their shoulders to sell from door to door. The seasonal hawkers were found selling mangoes, lychees and oranges at exorbitant prices and bargaining was the best part. The products were measured in front of your eyes with batkharas, iron weights.

During times of festivals, I remember one knife-sharpener-wallah, who used to come very early in the morning, and chanted "chhuri-boti dhar koraben?" House helps got excited to hear the voice of these particular ferriwallahs as that meant they could have the blunt knives and botis (a long, curved blade that cuts on a platform held down by the foot) sharpened, easing their workload.

The cheese-seller, with his salted and unsalted goat cheese (paneer) stock in an aluminium bowl covered with red cloth, often came to our place as he was certain that we craved Dhakai cheese. I could still relish the taste of that cheese. There were some fancy hawkers too who used to sell colourful glass bangles, laces, safety pins, ribbons, hair-clips, and other items, and usually swung by more during Eid and Puja celebrations. There was one exceptional type of ferriwallah, popularly known as kagoj-wallah, who used to buy things like old books, newspapers, and magazines.

I remember one book-seller who used to come with books, comics and magazines wrapped in white clothes, knotted tightly on the top. This was the only hawker who silently knocked on the door. He was very soft-spoken and often took orders for books, and we would all eagerly wait for his next visit. These types of book-sellers probably do not exist anymore.

Dhaka in 2020 is different from the Dhaka of the '70s and '80s. Growing up during that time, we were happy and content with the slowness of life. There was no real estate boom, no skyscrapers; most houses were 2-3 storied buildings. The landscape of Dhaka started to change for the sake of development. The booming shopping malls began attracting customers, and this led the hawkers or ferriwallahs to slowly fade away into the pages of history.

Sketch by Aeman T Rasul

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments