Under A Red Oak

Zara's long, slightly curly hair was hanging from the back of a white leather couch. She raised her head for a second and turned it right and then left. “Oh, my neck hurts!” she said to herself. She had been sitting like this for almost two hours now. She knew she needed to leave the couch and mind the million and one important things that were going on in her life but she was tired, mentally. She did not even want to open those kohl-lined eyes of hers; she feared returning to reality. She began to play with her left thumb, pushing it right, left, back and forth.

“Are you sure you want to spend the rest of your day on this couch?” Saadi asked with a smile. Saadi, Zara's husband, was a most loving and considerate man. Zara had always felt lucky being his wife. No, they did not know each other well before their marriage; they were not romantically involved in any kind of relationship. But things clicked on their wedding night -- they realised soon after they tied the knot that nothing could and would separate them from each other.

“No, I need to get up. Would you please find out if lunch is ready?”

“Bua has already set the table,” Saadi replied. “I am starving.”

Zara finally left the comfort of the couch, stretched her hands and then drew them toward her neck, which was stiff from sitting in one position for a long time. “Ouch!” she exclaimed as she massaged her neck and shoulders.

The couple sat at the dining table for the last time. They knew not then that they would not see each other in another two decades to come.

“Are you sure you want to go ahead with the divorce? I have already told you a thousand times that I do not need a baby," Saadi said. "I want to spend the rest of my life with you.”

“Come on, Saadi, you love babies. I love babies too but…,” Zara's voice cracked. She would have probably started crying hysterically if the maids were not around. She gathered herself, coughed twice to clear her throat and finished the sentence. “… but I can never have a baby.”

They saw doctors in Dhaka, Singapore, Bangkok and Delhi. They spent every taka they had in their savings account to travel to different countries and meet infertility specialists. But doctors everywhere concluded that Zara's uterine abnormality would make it impossible for her to become a mother.

“So what?” Saadi was shaking in rage. He pushed a bowl of chicken curry aside -- its thick, red, aromatic gravy spilled and spoiled Zara's favorite table-runner. He did not care. He would have cared if it were a different day and time but not today.

Saadi had been trying to persuade Zara to not leave him and this house for the last 6 months. But Zara, an apparently soft-natured young woman on the outside, was adamant about her decision.

Zara sat at the table, playing quietly with the rice and fried prawns on her plate. In an effort to appear perfectly normal, she stuffed some rice into her mouth. Saadi stormed out of the room without saying another word -- he did not even finish his food.

Zara knew every nook and cranny of their house. At night, she could walk around the house; she did not need the light of an electric bulb to find her way. She knew where to find her mug and the white ceramic jug to drink water from. She could walk around the house with her eyes shut and not stumble once, for it was her home, her first home; her and Saadi's home.

She too pushed her plate aside. The front door closed with a bang -- Saadi had just left the house. Zara washed her hands in the sink and went to their bedroom, where her bags lay on the floor. She spent the next hour running her slender, neatly-manicured fingers on every piece of furniture of the house. She touched her favorite crystals, and even sat on her favourite couch for a few minutes. After all, she was seeing her home for the last time.

20 years later…

Saadi was in New York City to attend a 3-day business conference. It was the last day of the conference and they did not have an afternoon session. “Finally, some relief,” he thought. He left the conference center with a chicken salad sandwich in one hand and a frappuccino in the other. It was mid-July and the temperature on his smart phone read 90 degrees Fahrenheit. He stepped outside the centre, which was on the 39th street of Manhattan. He loosened his navy blue silk tie. His white shirt was already showing signs of sweat. But even at 52, he was strikingly handsome. Strands of grey hair here and there on his head only added to his good looks.

Saadi waved at a yellow taxi, which stopped in front of him with a screech of brakes. Saadi jumped right in and said, “Central Park!”

“Are you new here?” the cabbie asked.

“Yes, my first time in New York. I am here for a business conference.”

Saadi read the driver's name on the back of the passenger seat, Shohid Ullah. He looked like a Bangladeshi. “Are you from Bangladesh?” he asked the man, who also seemed to be in his early 50s.

“I am!” the driver answered excitedly. Saadi and Shohid Ullah discussed politics, food and the economy until they reached the Central Park. Saadi tipped the driver $10, got off the taxi and started walking toward the park.

“Sir, walk straight and then turn to your left and then left again. You will see fewer people on that side of the park,” Shohid Ullah shouted from behind.

Saadi thanked Shohid Ullah for the advice and then followed his direction. “He was right,” he said to himself. Saadi checked a few trees before seating himself under a red oak, which was standing far away from the madding summer crowd.

The frappuccino cup was sweating in the July heat. Saadi took a sip and the coffee tasted watery. The whipped cream on top had already melted. The chicken salad sandwich, however, looked fine -- the lettuce was still crisp. He was looking around the park -- it was huge. “No, 'huge' is perhaps not the right word. The park is humongous,” he thought. Then he thought again if “humongous” was an appropriate word to describe a park.

Thinking such silly thoughts, Saadi looked around. There were literally only a handful of people in the spot where he was resting. There was a family of four picnicking under a maple tree. About 100 yards away from Saadi was a woman in an off-white skirt and a blue kurta sitting under another red oak tree. From where he was sitting, Saadi could not see her face. He could only see the woman's hair, which was long, slightly curly and ebony in colour. He wondered if she was Indian.

Taking the first bite out of his sandwich, he looked at the woman again, and then again. She was now pushing her left thumb right and left, back and forth. Saadi felt dizzy for a moment. Then he could not figure what he was really feeling. He thought his heart missed several beats. Then he felt his heart racing, beads of sweat forming on his forehead. He placed the half-eaten sandwich on the crumpled brown bag, brushed away bread crumbs from his black pants and stood up.

“It cannot be Zara. No, it cannot be,” he thought. “I cannot be so lucky.”

“Excuse me,” Saadi stood behind the woman, gathered all his courage and said. He felt his middle-aged heart missing another beat.

Zara broke out in a cold sweat. “The voice is so familiar, so familiar,” she thought. Even though she had not heard the voice in twenty years, she had not forgotten it. The voice belonged to the only man she ever loved, the man who she thought she liberated so that he could re-marry and become a father. Her heart broke the day she left “their” house. She could never mend her broken heart -- the cracks only widened with time.

Pain and loneliness seeped into those ever-widening cracks and swelled it. Now it was too heavy for her to even carry it around. She left Bangladesh and settled in the USA with the help of her brother because she wanted to flee the memories, which were beautiful but tormented her every minute.

“No, it cannot be him. He does not know I live here,” she shuddered at the thought of turning her head and finding out it was Saadi standing behind her.

Zara sat under the red oak with tears flowing. She had not even realised that she was crying until the sleeves of her blue kurta felt cold and damp. A sudden breeze from the south caressed her hair.

Saadi thought an eternity elapsed before Zara finally turned her head and looked into his eyes.

By Wara Karim

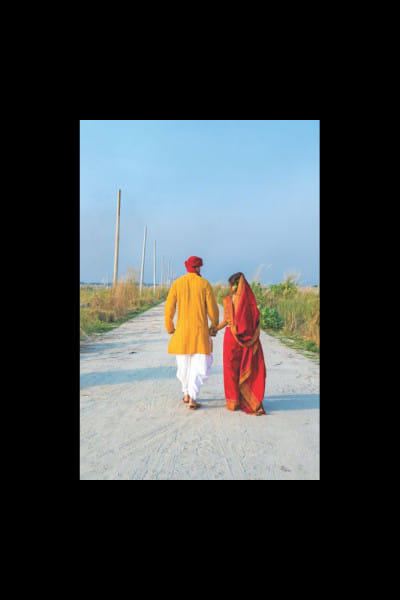

Photo: Sazzad Ibne Sayed

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments