Grace

Women's Rehabilitation Centre, Dhanmondi, 29th December, 1971

Gabriella is a 40-year-old obstetrician-gynaecologist from Australia, a godsend for the violated women spat out by the nine-month long bloody war of Bangladesh. She is a tall woman, almost like a lean pillar. Her hair is long and blond, caressed with dark streaks.

Her profession has exposed her to extreme degrees of cruelty, and she has always been an expert at easing her sorrow by the fact that she plays a role in repairing the women—helping in abortions, stitching up the vaginal wounds, waging war against the infections that trouble the affected females' genitals. It is as though the fact is an ointment to the grief that causes her pain when she witnesses the violated women's sufferings.

"Please take off your Burkha," Gabriella orders Sushmita.

Her assistant, Manzoor, translates it for Sushmita. "Madam, apnar Burkha ta khulen. Daktar bolechen."

Gabriella is not taken aback by the hideousness of her presentation. It's because she is used to seeing the women of war in their grim forms, the hideousness being mutual. The forest of thick, tangled hair, the bite marks running downhill from her nose to her collarbone, the shirt and lungi soiled and torn at places, the swollen belly with a baby swimming inside, her skin bearing evident signs of injuries, coated with layers of dark substance, possibly soot.

It's hard to guess Sushmita's age with the pregnancy. Gabriella assumes she is a teenager.

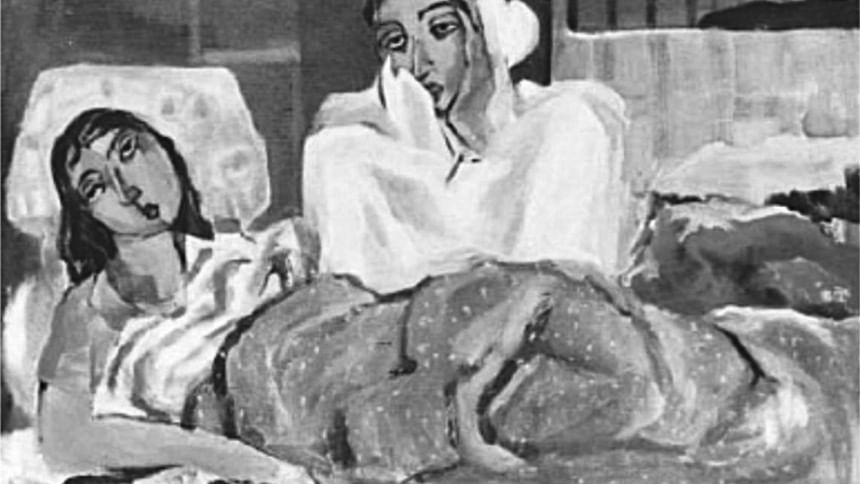

Sushmita wears a teak gown, the same colour as Gabriella's gloves, and spreads her leg as Manzoor translates whatever instruction Gabriella gives. She lifts up a microscope and holds it under a giant, mechanical eye attached to a handle, just above Sushmita. She examines her swollen and bayoneted breasts, her swollen and bayoneted vagina. She applies antiseptic medicine all over her wounds in silence, her mask hiding her inquisitive and wincing facial expression, rendering her a glassy robot just doing its job. The examination, the application of antiseptic, and giving advice on treating the wounds later on are part of a monotonous ritual for Gabriella.

—"So where did you come from?"

—"Cantonment."

—"Age?"

—"17."

—"Where is your family?"

—"I don't know."

—"Did you visit your home before coming here?"

—"No. The government people brought many of us here in their trucks from the Cantonment."

—"Do you wish to call your family?"

—"No. "

Gabriella knows how the conversations with such patients proceed. Manzoor does too, after all, he is the bridge through which the languages travel and meet each other. Besides the repetition of her job, she has to embrace the repetition of such conversations as well. She has seen how some of the victims were received by their families with open arms. She has seen how some of them were ostracized. She has seen how the women had many battles to fight, how the liberation of the country meant very little for them. She couldn't wrap her head around the fact that the deeply rooted misogynistic and patriarchal perception made the victims powerless, hacking at their bones until they became powdered.

It turns out that Sushmita is seven months pregnant.

—"Are you willing to keep it? It's very dangerous to abort it now. You can give birth and put the baby up for adoption. There are many foreigners willing to adopt the babies born here."

***

Sushmita doesn't know where her parents are. Have they fled to Sylhet? Do they still polish shoes at the Railway Station? For a moment, she thinks of making an attempt to find them at the Kamalapur Railway Station, where they used to live. She doesn't even know whether they are alive. And even if they are alive, she doesn't feel it right to show her face before them. The last time she saw them they were begging the Pakistani soldiers to kill them instead of defiling their daughter. It was the black night of 25th March. They were forced to see the act playing out right in front of their eyes. At one point, Sushmita was hit by a bayonet and fell unconscious.

She suppresses the thought of finding them, gulping it, hoping it never floats up again.

A Hindu girl violated at the hands of Muslim soldiers. What a disgrace. The notion hovers above her all the time like an evil bird warding off the peace she deserves.

***

Sushmita stands under a running shower—hot and long. She crosses her hands over herself and recalls the days of captivity. She tries hard to forget those days but the bruises on her skin, the bite marks of the predators, and the bayonet-inflicted injuries keep her eyes open to replay the days in the camp, not allowing them to close, to forget. It's almost involuntary. She thinks of one of the fellow captives, with whom she grew quite friendly during the period of captivity. Bijoya. She was 15. When the Mukti Bahini rescued them from the Cantonment, her brother clutched her in a hug, breaking into tears. Her brother was in the Mukti Bahini. She remembers how seeing Bijoya so happy locked in her brother's embrace saddened her. She has been fiddling with the thought of her parents ever since. If they get to know that she is here in Dhanmondi, will they come to pick her up? Or would her theories of estrangement turn out to be true? Many questions crowding Sushmita's mind never end.

Sushmita is asked to meet Dr. Gabriella since a list of adoption is to be made for the Christian missionaries that are helping in arranging international adoptions.

—"Do you want to keep the baby after its birth? We need to hear your decision soon."

—"I don't think I will."

—"Alright. Fill out the form. Sign here."

5th January, 1972

Gabriella is giving a lecture to the former captives on taking care of their damaged organs; the things they are allowed to do, the things they aren't allowed to do. Manzoor, of course, is translating her words. While the lecture continues, thin lines of water and blood run down Sushmmita's legs, soaking her white sari and covering the mosaic floor. She needs an emergency C-section.

A crying baby is taken out of Sushmita's womb. It is a girl. She is longing to see her mother's face. She is longing for the motherly warmth she deserves. But Sushmita is no more. Her mouth is gaping, her eyes open and fixed at the direction of the door. So for the time being, Gabriella holds the baby delicately, her eyes welled up, baby-talking with the little crying machine wrapped in pink cloth.

Sushmita's phantom kisses the baby on the forehead, caresses its little fingers and toes, then it shoots towards the ceiling of the OT, flying out of the Rehabilitation centre, out of Dhaka, out of Bangladesh, into the space, where the souls of the dead welcome her with flowers as celestial bodies shine in the background. Her parents aren't there, among the souls of the dead. They are indeed alive. On the earth.

This is the first time Gabriella has observed a mother's death during delivery in this war-affected country. The grief of the moment overwhelms her, holds her senses under its clutch. She feels a sudden urge to protect the screeching baby. The baby with soft, pink skin, a pillowy appearance, a tender innocence, a brutal origin, and motherless first moments. It is as if an unseen hand has set the dormant mother inside her free. Although she could stay stress-free once the baby was sent to the missionary for an international adoption, the gravity of the moment holds her still, fixates her on the subconscious decision to adopt the baby, unplanned. Gabriella has never thought of getting a baby until now. Perhaps, it was the emotional vulnerability of the moment that hung in the air. Perhaps, it was the tragedy tied to the baby's birth. Perhaps, it was the innocence of a baby born of violence.

She knows the baby will fly to Canada when it finds its Canadian parents within a month or two. She knows it is destined for a good life. She knows she doesn't have to worry about its safety. But still, she swims in the strangeness of emotions, in their unpredictability. She feels vulnerable with the baby held in her arms. She thinks it's a delicate bird, meant to be touched lightly so that its bones don't snap. Its rhythmic and shrill cries make Gabriella want to cry her heart out, set her tears free, like a dam breaking, flooding the valleys below. Emotions indeed are strange. They make Gabriella take a decision in the spur of the moment. A decision that is linked with someone she didn't know well. A decision that ties her to a war-torn country.

After a long while, when the baby stops crying and holds Gabriella's index finger lightly, she names her Grace, registers it in the diary, closes Sushmita's eyes, and puts a tick on the box that reads, "Adopted." Then she jots down her personal information on an appropriate paper.

"Ma'am, are you adopting the baby?" Manzoor asks.

She faces towards Manzoor, Grace in her arms. Tears run down her cheeks. A smile lights up her face.

"You are safe with me, little Grace."

The writer is currently a 12th grader in Birshreshtha Noor Mohammad Public College. He is a regular contributor to the Star Literature & Reviews pages.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments