Musing Home

For orchid people like us, a tree from a land called home brings a sweeping breeze of mirth. That breeze dances around us and stirs our leaves of memories. Sometimes it comes in the form of a visual presence, sometimes as a crisp smell of some known delicacies, sometimes, as a familiar clinking and clanking of a mother's tongue, and, sometimes, it surfaces as a name too common in a specific geographical location. But no matter in what form or force it comes, that 'homely' breeze always awakens some dead spirit, some old memories, or some new hopes. We feel happy for no reason, laugh louder than usual, and look softly at the strange place around us as if it was always a part of our home—a home waiting to welcome us back.

I was musing on this breeze of nostalgia sitting at a little Indian restaurant in Paris. We had arrived in the morning and wanted to have a Parisian feel before heading to the Sorbonne for a conference. After a nine-hours long flight, I was starving and was up for any food from any part of the world, be it Italian, French, or Turkish—as long as it offered me some vegetarian options. But my colleague Cecilia wanted something spicy. In honor of me, she wanted to have something from my part of the world, she said, and pointed at the signboard of the restaurant. 'Cardamom: Restaurant Indien.' I wanted to remind her that I did not come all the way from Florida to eat some Palak Paneer or Alu Gobi. But Cecilia's face was already glowing like turmeric as she 'discovered' the restaurant of her choice. I decided to let her be my Columbus for that day.

A young gentleman greeted us in French and handed us a menu book written in French. I took out my phone to use the Google translation app, while Cecilia tried gurgling out somewords in broken French. The gentleman's facial expression told me that Cecilia's words sounded nothing but Greek to him. So, I approached him in Hindi.

"Bonjour," I said, "aap hindi jaante?"

The young man smiled. "Boliye kia chaiye," he said. "Aap vegetarian hai? Koi baat nehi. Palak paneer chalega? Awr Uski liye chiken tikka masala?"

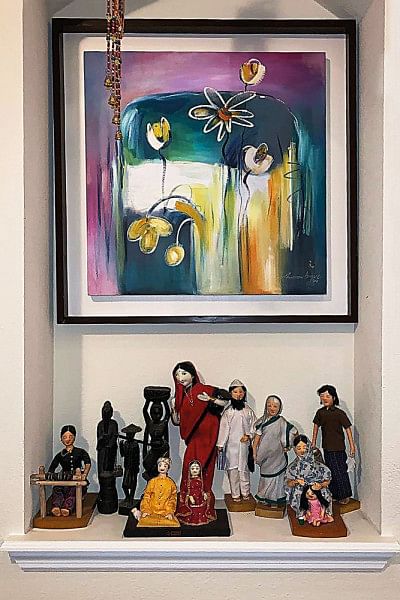

We nodded to his suggestion and ordered some tea. I was instantly impressed with the décor of that restaurant. There was a colorful display of paintings and handcrafts all around us.

"We have similar kind of artistic tapestries and handcrafted dolls in Bangladesh," I told Cecilia. "It's amazing how we easily feel at home in a strange place when you're familiar with the cultural heritage."

"For my mother, home was a shawl she brought with her when she left Cuba," Cecilia said. "Her mother wrapped that shawl around her and kissed her goodbye, before sending her to the US with a bunch of relatives. My mother never went back home. My Grandma died before I was born. But I remember her as a shawl, which my mother never allowed me to wear. She was very protective of the shawl."

"Of course she was," I said. "It was her home, not yours."

We sat there, sipping our tea and talking about similarities among dissimilar cultures and people from around the world.

"Hamara masala chai… pasand aya?"The young man interrupted.The cardamom masala chai was their specialty, he told us. He was a man in his early thirties. Stress had made an effort to imprint wrinkles on his forehead but failed to corrupt his smile. His eyes were bright and his smile was cordial. In his broken Hindi, he told me how glad he was to be able to speak with an Indian. Theirs was a local restaurant hardly visited by tourists. It stood at the corner of a street named Rue de Charronne, far away from the hubbubs of the tourist area. The nearest tourist spot was the Bastille, which was about four miles up north, the young man informed us.

"How far is the cemetery from here?" I asked. "I mean the Père Lachaise Cemetery."

"Wuo to iyanha se bahut door hey! Aapko udhar keya dekhna?" He looked confused.

I smiled in response. How could I tell him that there are at least a thousand reasons for me to visit that cemetery? Héloïse and Delacroix and Frédéric Chopin and Molière and Proust and Balzac and Gertrude Stein—all are resting there—eternally. It is also the final home of a man named Oscar Wilde. This young man would not understand what Oscar Wilde meant to me. Upon my insistence, he gave me the direction to the cemetery. It was about five miles in the south and a difficult walk for foreigners like us. Uber should be our only reasonable choice, he sugggested. I assured him that we were strong and fearless enough to walk through those cruel cobblestone streets. But he did not look convinced.

Meanwhile, Cecilia was enjoying every bite of her chicken tikka. The naan with fromage was excellent, she said, and so was the spinach and cheese curry. "The French knows how to cook Indian food better than the Americans!" Cecilia gave him a big smile. I translated her compliments for the young man, who smiled back and bowed at her.

"Quel est votre nom?"Cecila wanted to know his name.

"Alam," said the young man.

"What?" I was genuinely surprised. "Ye Bangali naam lekar tum Indian keyse baan geyi?"

"Hum India se nehi, Bangladesh se."

"Sheta aage bolbe na?"

"Apa, apni Bangaladesher?" The young man started laughing as if something miraculous had happened. Suddenly, it felt like there was a big tree right in the middle of that quaint little Indian restaurant—a tree that moved its branches and tossed its leaves as if awakened by a jovial monsoon wind.

From that point on, Alam chattered nonstop about his life in Paris and about his family back home in Sylhet. He took out his phone to show me pictures of his beautiful wife named Dalia and their nine-months old son named Arham. Their immigration process was complete and they would arrive in France any day now, he said excitedly. Cecilia and I were ready to leave but Alam was reluctant to let us go. He kept giving us important pieces of advice about different areas of Paris, asking us to be vigilant in the tourist areas, especially around the Eifel Tower and the Louvre. I paid attention to his every word, not because I was in need of tourist information, but because of the peaceful homely breeze that he was generating around me, showing his concern for us—for me—whom he had already started calling 'apa,' his sister. The sound of concern in his voice reminded me of my siblings back home in Dhaka. But what is home? I kept thinking. Is home where we are from, or is it where we return? Is home a place where we will never go back? Is home nothing but a bundle of ragged old memories or a requiem for unrequited dreams? Is the idea of home a myth?

"Amaar barite esho. Come visit my home. I'll take your son to the Disney World."I told him as we shook hands.

"You must come again when Dalia is here. She'll cook for you the best vegetable dishes from our homeland."

We exchanged our phone numbers and addresses of our homes in Paris and Florida. As we walked toward Père Lachaise, Cecilia teased me for being too generous.

"You left him a tip twice the amount of the original bill. Would you have done the same if he were French?"

"Well, he is French, isn't he? A French from back home—a home where neither of us will return." I sighed.

I looked back one last time and saw Alam, still standing outside the restaurant, waiving his hand and smiling, as if sending towards me a fresh breeze from a home that will never be ours anymore.

Fayeza Hasanat is an author, translator and educator. She teaches at the English Department of the University of Central Florida.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments