The Journey Back Home

During the Pakistan days my father was in the army, and we moved frequently, every few years. Soon after I finished Grade 10 in 1966, we made a big move: from Chittagong to Rawalpindi. A few years later our family moved again – this time from Rawalpindi to Abbottabad, then from Abbottabad to Lahore and finally to Quetta, near the Pakistan-Afghanistan border.

After the liberation of Bangladesh in December 1971, the Pakistani government interned the Bangladeshi military personnel and civilian bureaucrats along with their families living in West Pakistan. In late 1973, after the signing of the India-Pakistan-Bangladesh War Repatriation Agreement, we made our final journey back home from the confinements of the Quetta military camp.

Now it is the year 2020. I look back forty-seven years to reminiscence life's one of the most memorable journeys.

There is a prelude to the journey and it relates to the time we spent at Quetta's military internment camp. There were two main problems during the internment: cash – my mother had to sell all her jewelry; and uncertainty – not knowing what the future would hold. So, the political breakthrough in late 1973 was a jubilant occasion. Time began to move again. Expectations ran high. We waited eagerly for the day to be announced when we could board a train.

At Quetta we were a family of five: mum, dad and we three brothers. Our youngest, at the camp, fell severely ill. He struggled between life and death but managed to survive. I was in Lahore at that time, busy with my final-year engineering exams. I only came to know about his ordeal after I joined my family in the camp.

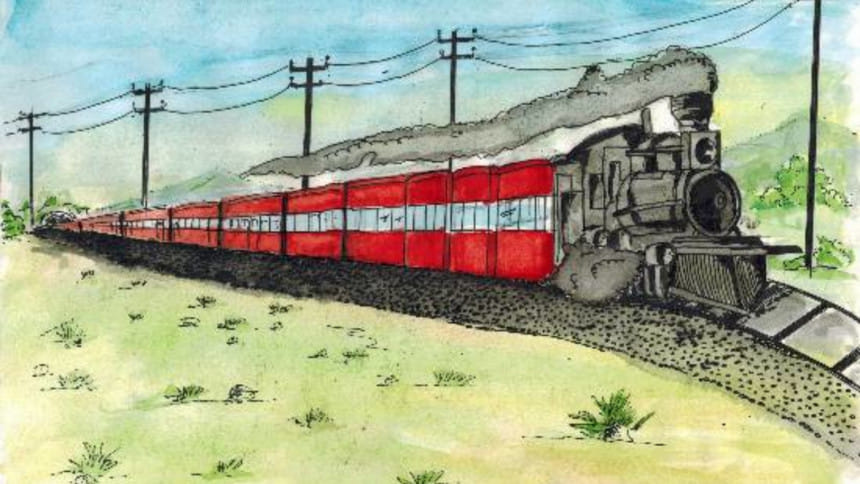

After a long, eager wait, the date was announced. We started packing. In the early hours of the appointed day, around mid-November 1973, we, along with the other detainees, began to board the military trucks. A short ride brought us to the railway station. Then the overnight train journey, some 900 km from Quetta (Balochistan Province) to Karachi (Sindh Province) took nearly thirty hours.

From Karachi railway station, we were trucked to a make-shift camp, much bigger than the one we left in Quetta. Here every family had to wait for their turn to board a plane. The Pakistani government arranged several commercial flights (KLM, Lufthansa, etc.) flying back and forth between Karachi and Dhaka.

After several days' waiting at the Karachi camp, we were scheduled to fly on a priority basis on the grounds of my youngest brother's ill health. It was a joyous occasion. Once we boarded the plane, the sense of relief was overwhelming.

After some two hours' flight, we landed at our long-cherished home carrying a few belongings. It was a new beginning as we started building our lives all over again.

Now, getting back to the main story, the long, arduous train journey entailed an emotional journey too. From birth to death, like passengers on a train, we are all on a journey back home. The passengers get off at their destined destinations: sometimes the next stop, other times the last one, in a distant land.

By the time the truck unloaded us at the Quetta railway station, the train was already full. It was a chaotic situation with men, women and children, accompanied by their luggage and provisions. We managed to board a crowded third-class compartment.

The occupants kindly made room for my mum, dad and our young brother. My elder brother and I, along with a few other young adults, stood alongside the piles of luggage, holding the rails overhead. We were prepared to bear any inconvenience for the sake of this much-desired dream: our long-awaited freedom.

This was a special train with a special consignment and tight security. We became increasingly anxious about the unexplained delay. The military police and security guards were probably making sure that all the detainees were accounted for.

While waiting, I remembered the movie Von Ryan's Express, a World War II adventure film starring Frank Sinatra and Trevor Howard. The screenplay concerns a group of Allied prisoners of war who conduct a daring escape by hijacking a freight train and fleeing through German-occupied Italy to Switzerland. Here in this train we were not making a daring escape, nor were we prisoners of war, but we were certainly prisoners in the hands of a powerful army.

At some point the whistle blew and shortly thereafter we felt a jolt – the wheels began to roll and the train was on the move. It was around midday and we were one step closer to home.

I had spent only the last few months at the camp and did not know many people there. So, I was not surprised that I recognised no one in the compartment. They were mostly young families with small children. The men appeared to be Non-Commissioned Officers. My father was probably the only Junior Commissioned Officer among this group.

We found ourselves in an unusual situation during our days in Rawalpindi – Pakistan's army headquarters. There was a shortage of JCO accommodation, so we ended up living in the NCO housing. Like our Ayub Line days at Kurmitola, we mingled and played with the boys whose fathers were mostly NCOs.

With her past experience at Goshalidanga Girls' School, Chittagong, my mother managed to get a teaching position at the Pakistan Council Nursery School, a distinguished nursery attended by the children of the top-ranking military brass. My mother got to know many of their wives, attended their house parties and mingled with their husbands including generals. She even once had a photo shoot with the most powerful man of the time: Pakistan's President, 'five-star' General Mohammad Ayub Khan.

Now, getting back to the story, the train picked up pace and got into a regular, cyclic rhythm. Our bodies and minds adjusted to this fast-moving, dynamic atmosphere.

As an instinctive habit, I looked around the compartment from left to right, looking at the faces one by one, discreetly, without making eye contact. I came to a halt, spotting something unusual.

A small boy, maybe three or four years old, lay curled up on his mother's lap, covered with a blanket. I could only see his face and it was milk-white. I looked at his mother. She was a young woman with fair skin. I thought the boy may have inherited his mother's complexion but with an even whiter shade.

Several hours passed and the train kept moving steadily through the Balochistan's mountainous region. With the sun behind the mountains, darkness began to shroud the earth making the compartment's light bulbs shine brighter.

The boy moved, waking up from his sleep. His mother looked for something to use, then helped the boy to urinate into a coffee mug, nudging her husband to help hold him still. When the father picked the boy up, I realised that he was much older – more like six or seven.

The mother passed by me as she proceeded towards the toilet. My eyes fell on the mug she was carrying and I froze. From what I saw in the mug I understood instantly why the boy was milk-white. I realised that little blood could be left in his veins.

Night fell and it was pitch dark outside. I saw the shadow of the compartment through the windows rushing at speed. My eyes were glued to it. It seemed I was riding the shadow, hurtling into the eternal darkness.

My feet were unable to hold me up any longer. So, I leaned against the luggage and fell asleep. When I woke up it was probably midnight. Neither the shadow nor the train were moving – I did not know why. Then at some point there was a mild jolt, which seemed more like a soft collision between two trains, and we started moving again.

Several hours later, I woke up with the first rays of daylight hurting my eyes. At the same time, in the midst of the train's clamour, I heard a sob.

Hours later when the train stopped at a station, three men hustled into our compartment: an army officer with two military jawans. The father carried the boy wrapped in a chador in his arms. My father accompanied them as they stepped down from the compartment and headed towards the lone railway station in the middle of nowhere.

The train with all its passengers stood silently in reverence. Hours later, the men returned after placing the milk-white boy in his final resting place in this arid, remote, wilderness – for him, a home of ultimate peace, tranquility and bliss.

A piercing whistle ruptured the stagnant silence. As the wheels began to roll, the grief-stricken mother sobbed again, covering her face with the blanket, probably trying to feel her child's warmth one last time.

Tohon is a short story writer for The Daily Star Literature page.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments