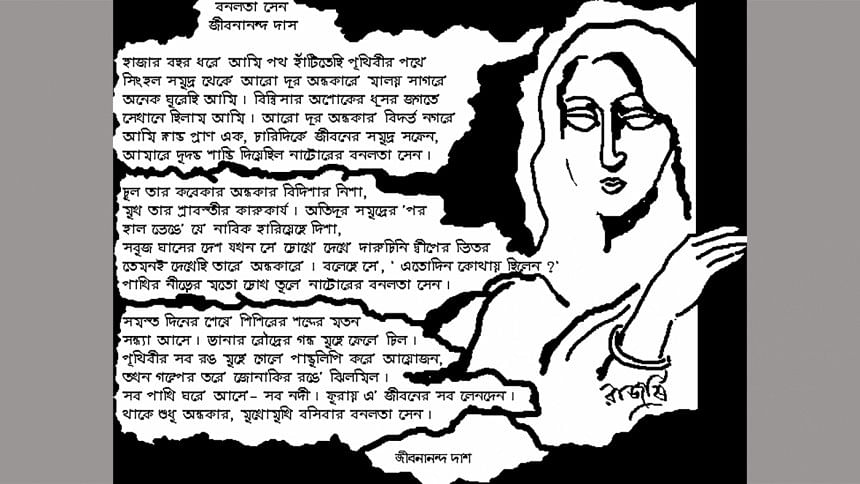

The Mona Lisa of Bengali Poetry

The process of reading is consummated in rereading. It is sure to deepen and broaden our understanding of the work and its author, and quite possibly of ourselves as well.

It is forty years since my first entranced encounter with Jibanananda Das in Ranesh Dasgupta's edition of his Collected Poems, and I have from time to time dipped into it to refresh my memory of one poem or the other. But it is only now, after the masses of his posthumously published works in different genres—poetry of course, but also novels, short stories, essays and journal entries—have startlingly revealed what an iceberg of an author he was, that I have begun my second, comprehensive, engagement with his oeuvre.

Almost at once I have been struck by the unsuspected depth of his impact on my youthful sensibility. Were it not for my immersion in the crepuscular world of his poetry, I now realize, my early outpourings in verse (albeit in English) would not have displayed such an image: "leaf to leaf/ trips/ smudge of shadow;/ dew-drops fall,/ soft as a hint or flicked ash" ("Two Trees and Time"). Nor such dire imaginings as this "picture/ of a perfect/ suicide—/ a drugged/ body/ lain lengthwise/ in the new-/ born waters of a spring/ as the/ thickening/ blanket/ of ice/ lulls/ faint heartbeats/ to sleep" ("Hill Station: Murree"; both poems are from my first collection, Starting Lines, Poems 1968-75).

As for my comprehensive critical take on Jibanananda, it will be a while before I can think of formulating it, but for starters I would like to share my (re)reading of his most famous poem. Much has been written on its eighteen lines—Saikat Habib, a Bangladeshi journalist, has even put together a 230-page anthology devoted entirely to it—but it remains enigmatic as ever. I think I can throw new light on the source of this enigma.

But first let me sum up the positive achievements of "Banalata" criticism to date. First, the poem's intertextual connections with other poems have been pretty thoroughly uncovered. Most conspicuously, there is a series of correspondences between "Banalata Sen" and Edgar Allen Poe's "To Helen": "ami klanto pran ek"//"The weary, way-worn wanderer"; "samudra safen"//"desperate seas"; "chul tar kobekar andhakar bidishar nisha"//"thy hyacinth hair"; "mukh tar sravastir karukarja"//"thy classic face"; "daruchini dwip"//""perfumed sea". Then again, the opening phrase of Keats's sonnet "On First Looking Into Chapman's Homer"-- "Much have I traveled"—seems to be behind Jibanananda's "anek ghurechhi ami." It has also been suggested that "daruchini dwip" may be derived from the "dur dwipbashini" in Nazrul Islam's "daruchini desh."

But these are only surface similarities; and let me hasten to add, lest anybody suspect otherwise, they do not make Jibanananda any more of an imitator than Shakespeare or Eliot. He was clear-headed about the role of a writer's reading in the strange business of writing. As he told Bhumendra Guha, one's reading impacts on the mass of one's experience, clarifies it, lends it a certain character, and if one is a writer or an artist one writes about this reshaped experience or represents it visually; it's a matter of an action eliciting a reaction. In making creative use of his reading Jibanananda is what Harold Bloom would call a "strong poet" who "for startled moments" can make us believe that the flow of influence has been reversed, that he is being imitated by the ancestors.

On the surface both "To Helen" and "Banalata Sen" are celebrations of the fascination exerted by feminine beauty, but even a cursory examination reveals that the underlying differences are more significant than this similarity. The former is a rather transparent construct in which a woman Poe admired (she is the dedicatee mentioned on its first publication, Mrs. Jane Stannard, mother of his friend Robert Stannard) is unambiguously conflated with Helen, who is of course recognized in the whole of western culture as the mythic embodiment of consummate feminine loveliness. But Banalata Sen is mysterious, because she cannot be simply equated to any personage, mythic or historical, or to any easily intelligible quality, abstract or affective.

This brings us to the second, more complex and more important aspect of the exegesis of "Banalata Sen." There are a number of perceptive readings, whose salient points I shall sum up and comment on, adapt to my own agenda and add to. The very name seems to have exerted a strange fascination on the poet, for it features in a novel and four other poems of his; one of the latter exists in two versions. Needless to say, these poems are far inferior to their famous cousin, and the ladies who appear in them are far less engaging than their famous namesake. One of them, "shesh holo jibaner shab lenden" ("Life's Transactions Come to an End"), is a fairly straightforward lament for the early demise of the lady. Another, "Bengali, Punjabi, Marathi, Gujrati," conflates a Bengali Banalata Sen, bearing a pitcher of water from the river on her hip, with a middle-eastern damsel offering a pitcher of intoxicant; the reader may be reminded of Coleridge's Abyssinian maid in "Kubla Khan." "Ekti Purono Kabita" ("An Old Poem") is a fanciful eight-line poem spoken by one come back from the dead and ending with the reincarnation of Banalata Sen. The two versions of "hajar bochhor shudhu khela korey" ("After a Thousand Years Spent Only at Play") dramatize a moment of recognition in an afterlife encounter between the speaker and Banalata Sen; but one version is set in this subcontinent and the other in ancient Egypt and Assyria.

These middle-eastern associations of some of the Banalata poems may lie behind the view (Sumita Chakrabarty's) that the Banalata Sen of "Banalata Sen" embodies the peculiar decadent romantic aura that is identified with the region (thanks to Orientalism of course). I will not quarrel with this as long as we remember that in its geographical as well as historical setting "Banalata Sen" is 100% South Asian. It takes us to the seas skirting Malaysia and Sri Lanka, evokes a cinnamon-isle in a simile (South India was famous for its cinnamon, we may recall), then brings us back to rural and mofussil Bengal. In time it takes us back and forth between modern Bengal and ancient India, characterized by puissant emperors like Bimbisara and Asoka, and fabled cities like Sravasti and Bidisa.

Banalata Sen belongs to mofussil Natore but the timelessness of her fascination is suggested by her metaphoric association with Sravasti and Bidisa. "Natore" to my mind possesses a crisp musicality, and ideationally, as Sumita Chakrabarty points out, it has Vaishnavite associations on the one hand, and, thanks to Rani Bhabani, with the feudal-colonial order on the other. Her face is the art-work of Sravasti ("sravastir karukarja"): we have a metaphor here, not a simile, so the impression is rather that the beauty of this Bengali woman has been transmogrified into a purely aesthetic entity, such as Yeats longs for in "Sailing for Byzantium." This dehumanized aestheticization is counterbalanced by the other historical metaphor for Banalata Sen: her hair is dark as the hoary nights of Bidisa. If the Sravasti metaphor is classical and Apollonian (and it is), this one is thoroughly romantic and Dionysian.

The image is one of hair let down, of a lady, en dishabille, in an unlighted nocturnal setting, clearly suggesting an illicit sexual liaison. The timelessness indicated by the reference to ancient history underscores the primordial and universal role of sexuality in human life, biological as well as cultural. Sanjay Bhattacharya, rightly to my mind, uses the Bengali word for an adulterous relationship, "parakiya," to describe the tableau; and at once the relevance of Natore's Vaishnavite connection becomes palpable.

Kaiser Haq is a poet, translator, essayist, critic, academic and a freedom fighter. Currently, he is the Dean of Arts & Humanities at the University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh (ULAB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments