The Story of Kusum’s Family

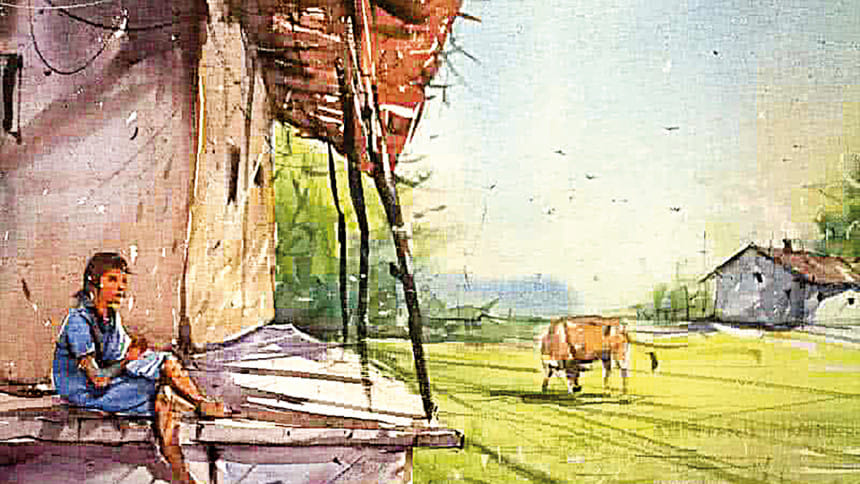

When the twelve-year old Kusum was returning home, she stole a glance at the setting sun for one last time. It was dipping over the heads of tallest coconut trees lined along the furthest edge of horizon. She let out a sigh — for some indefinable reason she wanted to stop and watch the sun disappear — her cheeks looked radiantly mellowed in the fading light as the brisk wind from the river that surrounded the village, her waist-long hair swayed freely from one side to the other.

"Oh, my mother needs me back home," she remembered suddenly. The fever had left her two-year old sister restless, making it difficult for mother to manage the baby all by herself. There was another task that needed her help. Her father hired two carts and told her mother to load them with all the goods of the tiny house where the family had lived for years. "You must load the carts by night; you may not have tomorrow," she heard his father tell her mother. Kusum panicked as she sensed the urgency of the occasion and looked upward at the clear sky of the windy June.

The house was still half a mile away when she came upon a field of paddy, it offered a vista of a sprawling expanse. A breeze rose up to romance with the juvenile growth of paddy stalks, a rhythmic undulation set in. The beauty of the twilight hours only heightened her pathos, as she struggled to hold back the tears.

"Do I have to leave my Kutti too?" she thought with a shudder. Kutti was a goat-cub that Kusum was very fond of. The cub followed her everywhere; given the space constraint, her father might not allow the pets to be taken along with them on carts. When life is uncertain for humans, how can one be so charitable to animals?

It was already dark when she came home. They lived in a house perched upon an uncertain tract of land, nothing is to be seen beyond the land as darkness ruled there. A lamp was placed in the middle of the front room — members of the house sat in circle around the lamp with solemn faces — the mood was deeply elegiac.

"Stop right there. Where have you been all day, girl?" mother shouted as Kusum attempted to enter the house, unnoticed.

"Shouldn't you be ashamed of yourself?" her mother continued, "Khushbu's fever is worse than ever and your father is fussing over every little thing!"

"I went to Munshipara to meet Shefali. Her father bought her new dresses from the town," Kusum lied.

Kusum saw no point in telling her mother that her heart contracted in pain as she bade a tearful farewell to the setting sun. Even if told, her mother would not understand.

Kusum left for the next room where her ailing grandmother was sleeping.

Her grandmother had a history of suffering headache for days. When that happened, women in the neighborhood would sit quietly around her, Kusum's mother would fill a bowl of rice mixed with jaggery and place it among the guests. Kusum would sit quietly at a corner listening to tales those women told of their husbands. She heard the story of her grandfather in this way.

Kusum's grandfather was a skilled boatman. There was a running joke that Majnu majhi loved his boat more than his wife. "He would leave before the Fajar prayer and return when it was dark. I would be the only person awake to serve him cold meal, his eyes were always awash with dream of the river," grandmother would say.

"He was a kid, the boat was his toy; I can still see how he moved nimbly up and down to fix the mast against the wind," she would continue.

"One day the river rose like an angry lion and devoured his toy; it ravaged the banks and the places we lived. Since then, its eating has not stopped, howling for sacrifices everyday- no one knows whose sins have brought us to this pass," grandmother would lament. "We searched for him all day and night — two days later he was spotted two miles downstream — caught with a raft of floating logs."

Kusum remembered the story well and knew that grandmother would repeat the narrative for the remaining days of her life.

That night it was Kusum's turn to watch over Khusbu sleeping in her tiny cot. Her mother needed rest. Close to the midnight, Kusum herself fell to a deep sleep and dreamt of an open field, kutti, a dead body washed ashore...

When she woke up with a start in the morning, she knew that something bad had happened: little Khushbu had crept over the side of the cot and fell, her mother's beautiful face livid with anger demanded an explanation. Kusum avoided making contact with her mother's eyes- she quietly made a beeline to the door and stepped outside.

Once she was outside, she was overwhelmed by the beauty of the early morning. Her eyes moistened with tears as memories came crowding to her mind. She remembered Shefali, her best friend. How many times they had played under the shadow of their favorite tamarind tree and played with a swing tied to the tree's topmost branch. She belonged to the place and the place to her, and only when it seemed that the bond would last forever, it was about to end.

Kusum spotted two carts close to the cattle-shed. Her father had hired them last night to take their belongings away to an unknown destination. She knew that men would cruelly dismember the furniture and fling them heartlessly into those carts. "They will destroy everything that had my childhood all over," she lamented.

She saw men from the local Union Parishad everywhere. Kusum knew that these men were visiting them not out of sympathy but to enjoy the spectacle of a family leaving their ancestral place.

Suddenly loud cries of women rent the air. Kusum felt her heart squeeze in an unknown fear; as she hurried home, the air felt keen across her chin. She expected the worst.

"Was it her?" Kusum shouted in panic as she burst in, her mother and grandmother, expressionless, sat like broken heaps of things in one corner of the front room. To her great horror, Kusum discovered that the back room where last night she stayed with Khushbu was gone. That room had fallen steeply into the fierce eddy of a river flowing with wild current and scheming to wipe out any piece of earth that came its way.

"The beast came early, why?" was Kusum's desperate question to God. The river was supposed to hit their land in the afternoon.

Kusum could not believe what she saw then- the foaming water had quickly swallowed everything of the room save the wooden bed where two-year old Khushbu sat like a jewel in the crown of an untamed beast.

"Please, save Khushbu! She can't swim yet." Kusum's voice was unearthly, loud yet meaningless. Khushbu had reached a point beyond any human intervention to save her.

The wooden bed that was carrying the baby like a makeshift raft was accompanied by a flotsam that included among many things the dolls and rags of the baby. The baby was too shocked to produce any sound. Her chubby hands rested helplessly on the wood as her tiny eyes were desperately searching for her mother:

Then water started to rise around her.

"Whose sins brought us to this pass?" Kusum asked, this time, to her own self only.

Yasif Ahmad Faysal teaches English at the University of Barishal.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments