The World is a Mirror of Water: Musing on Lalon and Beyond

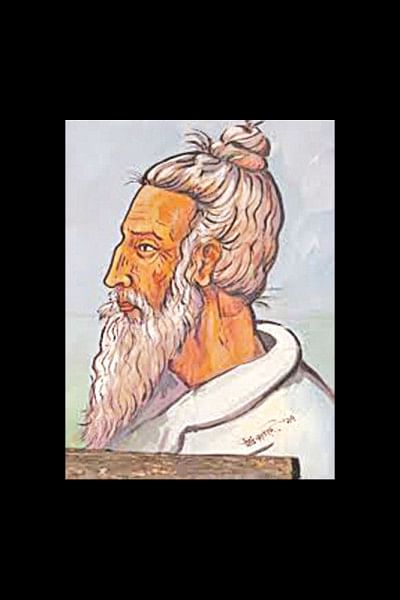

It always amazes me how a simple illiterate man—'sahaj manush'—from the rural nineteenth century Bengal could have had such a magnanimous vision to assimilate in his songs the core ideas from the Vedic, Upanishadic, Vaishnavite, Buddhist, Tantric, and the Sufi philosophy. Issues of religion, gender, class, caste, nature, the ontology of human body and spirit, along with the origin of God and/or the Supreme Soul—all these and more were his subjects of query. This man is so engraved in our culture's DNA that we cannot think of our literary heritage without him. He is the silent voice in our head that asks us to be aware of the existence of an unknown bird that freely enters and exits our body's cage. This Baul—Lalon—died 128 years ago, and yet still lives within us, constantly goading us to seek out that Soulmate of ours—our "Moner Manush," "Odhora Chaand," or our "Ochin Pakhi."

While flipping through the pages of an online anthology of Lalon's songs, I felt tempted to ponder a little on his use of what is known as the Sahajiya philosophy. The Buddhist Sahajiya emphasis on the body as the true site and paraphernalia of worship is indeed a recurrent message in Lalon's songs. The Baul songs are soaked in metaphors, and meanings are only evident to those that are initiated into the Baul faith. Needless to say, this metaphorical style of writing has its origin in a text that was composed centuries ago, by a group of ascetic leaders, who tried to explain the esoteric and erotic themes of their Buddhist Vajrayana and Sahajayana beliefs through their songs that are now known to us as the Charyapadas. For Sahajayana, the supreme wisdom lies within human body. A good number of Charyas focus on the issue of self-knowledge that can be achieved by showing reverence to the human form. As we already know, the songs in the Charyapadas were region-specific representations of the socio-cultural aspect of the agrarian and the riverside lands of Bengal. And we also know that the Charya songs were written in metaphoric or mystic language ("sandhya bhasa") and the mystery was meant to reveal to those who had access to the inner meanings of those songs. According to the Sahajiya faith, the body, the mind, and speech can attain the Supreme Knowledge with the guidance of a guru, who is expected to teach the disciple how to control the fickle mind and the erratic body.

The Charya poets delivered the truth about the Supreme Knowledge in poetic form, using various elements of nature as recurrent tropes. Rivers, trees, boats and boating implements are constantly used throughout the Charyas as spiritual symbols. Such use of nature as an essential symbolic element and the emphasis on the human form as the metaphorical site of both the quest and the goal initiated my interest in reading the Charyapadas side by side with Lalon. Since I am not writing, but only musing here, I will try not to bore my readers with my (pseudo) intellectualism. I will briefly reflect on the influence of the Sahajiya faith on Lalon, using my own translation of some songs from the Charyapada as my reference source. Because selecting a Lalon song is a difficult task for me (I am that biased), I will use his songs as a general platform and compare them with specific examples from the Charyapada, leaving my readers with the liberty to connect my thoughts with their favorite Lalon songs. I am not an expert on Bengali history and literature, and my knowledge of the Charyapadas is outrageously inadequate. I hope the reverend Charya experts of my country will forgive my boundless audacity here.

Lalon, being a Baul from the riverine region of Bengal, has used rivers and boats as dominant symbols in many of his songs. He examines the bond between the preceptor and his disciple, the quest for the Supreme Soul, the seeker's desire to surrender to the Sahaja path disregarding the illusions of the world, and the futilities of excessively religious rituals, among other things. He then places all these in context of a journey through the river (or sea), on a boat, which needs an oar as its steering force. Sometimes, the seeker's body is the boat, lost in the vast river, and the guru's instructions work as the oar. Sometimes the lonely seeker sits on the shore, waiting for direction and hoping to be saved by the grace of the Benevolent One.

Now read Charya 8 in my translation, as an example of a thematic similarity. In this Charya, Kambalambara uses the metaphors of a boat, the oar, and the river:

"The boat of compassion, loaded with gold,

Leaves no room for silver to be stored.

Steer your boat, Kamali; row it skyward.

Can the birth that is past return from the dead?

With the peg removed and the rope released,

Kamali, ply your boat as the guru advised.

While in the mid-stream, look around everywhere,

Who can row a boat if there is no oar?

Swerve left and right, but keep your aim unbreached;

The bliss of 'mahashukha' will thus be achieved.

The first line of this charya reminds me of Tagore's "Sonar Tari," and the whole poem takes me to the land of Lalon, where the lonely speaker eagerly waits to go to the "city of mirrors" to meet the "neighbor," but finds no boat that could take him there. This "neighbor" lives so close to Lalon, and yet it feels like they live millions of miles apart. If our body is the boat, the mind is the oar, and the shoreless sea is this world of illusion, then the boatman for whom Lalon waits is the Supreme Soul whose magnanimity can only be perceived through a guru's guidance and by adhering to the Sahaja path.

Charya 38 also resonates the same urge, where the poet Saraha says:

"In the body's boat, the mind is the oar.

Under Guru's guidance, hold the steer.

Calmly row that boat of yours;

There's no other way to reach the shore."

Centuries later, Lalon emerges on the same note and sings, "Par-e loye jau amay," hoping to be saved from the world of illusion before his rotten body of a boat—being filled with sins and temptations—breaks apart and sinks in the mid-sea.

In order to attain the Truth (or salvation for that matter), Lalon seeks guidance from Seraj Shai, and his yearning intensifies from his realization of the fact that the Infinite Void (Supreme Soul) resides within one's Self. One who knows this truth will not wander around the world in search of it, or will not waste his time counting prayer beads. Saraha expresses the same notion of the Sahaja path in Charya 39, when he says:

"O my Mind, it's your own fault that your hands are empty.

Without your Guru's blessings, how can you continue the journey?"

Saraha then talks about the temptations and sufferings in the world and concurs that the Self is the Void—the Ultimate Truth (within):

"So unusual are these worldly illusions that it brings the strangers close;

The world is a mirror of water; Self is the void that the Sahaja unfolds."

In a song, titled, "Ache jar moner manush mone," Lalon sings of the futile search for the Mate who lives within the Self. One does not need to call this Soulmate aloud, because he lives nearby and has access to everything and everywhere. Lalon reminds us of the sore in our hands that needs more rubbing and the suffering souls that need more nurturing. It is not the excessive ritual practices that will nurture our sores; instead, it is our ability to comprehend the immense mysteries hidden within the human form and our willingness to follow the instructions provided by the guru that will help us fathom the unfathomable presence of the Infinite Void within the Self.

The world is a vicious place, the river is dangerous, the body is tempted, and the mind, fickle. Santi, the poet of Charya 15 therefore warns us:

"Fool, don't dwell on the shore; the Sahaja way is within this world.

Boy, don't be misguided by the slightest bend; enclosed runs the royal road.

Deluded, you can't fathom the deep sea of temptation.

Neither a boat nor a raft can you see, nor do you ask for direction."

Lalon, the wandering Baul, does not want to "dwell on the shore" like a fool anymore. He refuses to be deceived by the world that is nothing but a "mirror of water" (Charya 39), and because he knows "there's no other way to reach the shore" (Charya 38), he implores the eternal Boatman to help him cross the shoreless sea, singing earnestly: "Par-e loye jau amay."

Fayeza Hasanat is an author, educator, and translator. She teaches at the University of the Central Florida, USA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments