Three, Not Three

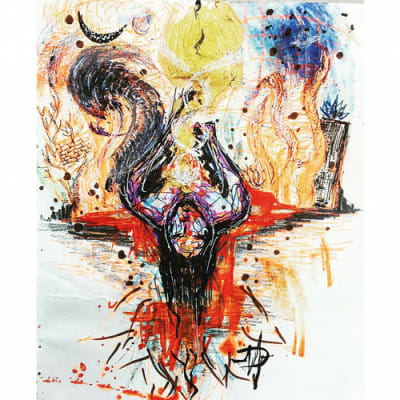

In the farthest end of the horizon across the river by the edge of a forest surrounding the dark hills sat a cottage made of dried palm leaves and rattan sticks in which lived an old woman. She was lonely like the hills that stood alone, the trees that wrapped the forest, and the river that ran, piercing through the woods and hills—like a three not three. The old woman was very old, but not too old to not remember how to see her life in three fragments—of past, present, and no future—or how to distinguish the hills from the river and the forest, and find herself lost in all three of them, or how to see morning, noon, and night as nothing but an endless struggle to forget the pains that she hardly recalled. She was too reluctant to reason and too placid to remember her name and her home, but she was not too old to not remember what a three not three looked like, or felt like, especially when it entered a woman and swirled inside of her, as if to make room for the drooling knives waiting for their turn to enter her secret cave—the cave that every woman carries so that one day some men would enter and howl a shriek of victory—over the woman whom they bed or over the land on which she lies—bare, gutted, ripped, raped—not once and not by one, but by many and for countless days and months. The old woman was not that old, but she was too old to be drowned in her memories of fears. People did not care for her—a raggedy crazy woman that she was—and useless too. She did not care about people's apathy because she was afraid of them, especially of men. She lived in the woods because she felt safe around wild animals and in wilderness. Once in a while she would go to the nearby village to beg for food. But most of the time she depended on the forest and the river for her nourishment. She was afraid of the night. Because night brings out earth's darkness, and people's too. She had been afraid of night since she was fifteen and had not slept at night for fifty years. She would sleep all day and then wander around the forest all evening in search of food, and then she would come back to her hut and wait for the night to be over, holding a rusty knife tightly clasped in between her two craggy hands.

One such night, while sitting inside her lonely hut guarding herself from the silent night outside, the old woman heard some strangers—shouting and scolding—asking someone to shut up and lie still. She heard a woman's voice—pleading for mercy—to some men and to God. "O Allah, let me die! Why don't you take my life Allah—and spare me this pain? Do whatever you want to do with me, but let my little girl go. Don't you have mothers and daughters at home?" The woman kept pleading until her voice failed. Someone yelled ecstatically and someone cheered. The old woman was old but not too old to not remember the joyful hisses of lustful men. Her hands tightened around the wooden handle of her weathered knife, and her head that had had no trace of sanity for years suddenly became alert in anticipation of danger. She unlatched the door and stepped outside in the dark, holding a knife in one hand and a bamboo stick in the other. She saw a gang of men, laughing, roaring, and drinking—feasting on two female bodies that lay unconscious in the pool of their own blood by the river bank.

Two

The old woman flung her knife at the man who was hovering over the little girl. As the knife flew by him, slightly cutting him on his shoulder, the man jumped off his prey. One of the men attacked the old woman from behind and wrestled to grab the bamboo stick from her. She twirled the bamboo pole hitting everyone and anyone who came near her. All the while she kept screaming and cursing at those men, challenging them to fight her if they had the courage.

"Where the deuce did she come from?" a man yelled.

"Crazy bitch! Get out of here before I kill you!" said the one struck with the knife.

"We should kill her. Else she'd tell everyone." Another man said.

"Forget her. No one will believe this mad old bitch," one of them said reassuringly.

"Let's go anyway," said another. "We got what we wanted, didn't we?"

"But wait, let me get some souvenirs of our nightly fun." One of the men chuckled as he raised up his machete and chopped off a bruised breast from the unconscious girl's rampaged chest. Then he thrusted the machete through her parted legs and shredded her inside like a piece of paper. The girl groaned until she went numb in pain. The other woman—the girl's mother—lay unconscious, while the butchers played with her daughter's body and laughed in sheer amusement. The old woman attacked them with her bamboo stick but they snatched it away and pushed her on the ground.

"Don't try to go to the police. We've recorded everything on our phone. We'll come for you and make a whore out of you if you rat us out." One of the butchers hissed at the girl. The girl, unable to move or talk, shed her silent tears and watched those happy men—eight of them—who went back home to be someone's loving son, brother, father, or husband.

Three

The old woman used a part of her torn sari to bandage the wounded girl's chest. She then sat beside the mother and shook her vigorously.

"Wake up! We've to leave this place before they come back. Wake up! We've to save your daughter!"

When the mother finally opened her eyes, the old woman asked her to stand on her feet and help her carry the wounded girl. "We have to run fast before they come back. Now get up and get going." She pushed the mother on her side and pulled her by the hand. But the mother still lay there, as if lifeless.

"My baby, my little girl, will she be okay?" the mother asked.

"Yes, yes. The Muktibahini will save her. Maybe they're already on their way."

"Who?"

"The Muktibahini. They're fighting those thugs, don't you know?" The old woman was visibly shocked. "Don't you know the country is at war? The enemy soldiers are everywhere—killing and raping and looting. And then there are these thugs who come for you. They came for me too. They said they were peacekeepers and asked my father to help them retain the country's peace by handing me over to them for the military. They killed my father and took me with them to their sanctuary where they tore me up and ate my flesh before delivering me to their masters. I was fifteen and scared. Unfed, unclothed, and chained, I lay in their bunker, carrying in between my legs a dark cave—for the vermin to crawl in and out all day long. I was not alone though. There were many other caves in that bunker and the rats crawled in them too. Some of them choked us. Some of them cut us inside—not with machetes though—but with bayonets or rifles. Three-not-three's. Some of us lost reason, some of us died, and some of us waited for the light. Then one morning, the Muktibahini came and saved us. They'll save your daughter too."

"The war has ended fifty years ago, long before I was born," said the mother. "There's no war. And there's no Muktibahini." The mother lay by her wounded daughter and kept sobbing. "No one will help—neither God, nor men."

"The war has ended, you said? The enemies are gone? Then where did those thugs come from? Why did they do this to you? If the war has ended, then why does this place look like a battleground? I don't understand this." The old woman looked confused. "There's no Muktibahini? Then who will save this little girl?" Feeling utterly helpless, the old woman lay down by the mother and started crying.

The night was dark. The river was calm and the hills were asleep. The old woman's hut was empty like the shadow of the woods. And amidst all darkness, in the blood-soaked grass by the river, lay three women. But they were not three anymore. Only one of them was alive, awake, and waiting: crazy with hope.

Fayeza Hasanat is an author, academic, and translator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments